The meteorite effect

Photo courtesy of the Buseck Center for Meteorite Studies.

By Bret Hovell

Editor's note: This story is featured in the winter 2025 issue of ASU Thrive.

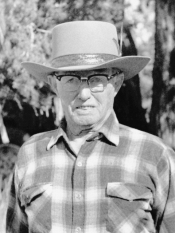

On Nov. 9, 1923, Harvey Nininger saw his future explode across the Kansas sky. He would become perhaps the single most accomplished collector of meteorites ever, and that collection would seed generations of cutting-edge space research at Arizona State University.

But at that moment, Nininger had only just become aware that meteorites even existed.

He was teaching biology and geology at the small McPherson College in Kansas, about an hour’s drive north of Wichita. And he considered himself a knowledgeable man, especially about the sciences. So when he read, that previous summer, an article in Scientific Monthly about meteorites, he was fascinated.

“All during my childhood meteors were regarded in about the same light as ghosts and dragons: mentioned rarely and never discussed seriously,” he wrote in his 1972 memoir, “Find a Falling Star.”

Now, Nininger longed to see a meteor, and a meteorite, for himself. As fate would have it, he did not have to wait long.

That chilly November evening, Nininger was walking home from campus, chatting with another McPherson professor. They paused in front of the colleague’s house when suddenly, Nininger wrote, “A blazing stream of fire pierced the sky, lightening the landscape as though Nature had pressed a giant electric switch.”

His companion was speechless. Nininger, however, bent over and made a mark on the sidewalk, beginning to calculate where the space rock, as he immediately suspected it to be, might have landed. He vowed to hunt for it.

“And his friend said, ‘You’re nuts!’ But he wanted to find it,” recalls Nininger’s grandson, Gary Huss, the director of W.M. Keck Cosmochemistry Laboratory at the University of Hawai‘i, who was previously a research scientist at ASU. “He thought that was the most fascinating thing he’d ever seen.”

That first hunt would lead him to meteorites — though not, as it would turn out, the ones he saw streaking over his head that autumn night. And it would inspire him to commit, first to a hobby, then to a life, of searching for and cataloging them.

“He was just obsessed, if you will, with finding meteorites,” says Kenneth Zoll, the author of a recent biography of Nininger called “H.H. Nininger: Master of Meteorites.” “And he was convinced that nobody was paying good attention to the field. And he was right.”

Nininger worked without institutional support: He wasn’t part of a university, he didn’t cash checks from the government. Very few meteorites had been found up to that point, and for the most part scientists thought everything that could be learned from them had been.

But Nininger proved that belief wrong. Working with his wife, and later with his children and their families, Nininger expanded knowledge of both the number and kinds of meteorites that had fallen to Earth, while developing the “collecting methods, cataloging and displaying of meteorites (that) are in many ways still the standard,” Zoll writes.

He was just obsessed, if you will, with finding meteorites.

Kenneth ZollAuthor of "H.H. Nininger: Master of Meteorites"

Eventually he moved to Arizona to be closer to Meteor Crater in Coconino County. And he continued traveling the country, collecting samples.

A Harvard professor named Fletcher Watson wrote in his 1956 book “Between the Planets” that “for several years, Nininger was accounting for half of all discoveries in the world.”

But hunting for meteorites did not pay the bills. As Nininger aged, he realized he would need to part with the fruits of his life’s work. After selling part of his collection to a museum in London, American suitors for the remaining space rocks began to make serious proposals. ASU was among them.

The university was at a turning point. Just a few months earlier, ASU had been Arizona State College. But with its new mandate as a research-focused institution, ASU’s leadership saw an opportunity to capitalize on the urgency of the post-Sputnik moment and move into a research area that, they suspected, would only grow. With the help of a grant from the National Science Foundation, ASU paid $275,000 for the meteorites, roughly $3 million today. This year marks the 65th anniversary of that ambitious purchase.

Nininger’s work anticipated the space age, and it proposed to grapple with a question humanity has always asked: What else is out there? Now, ASU would turn its attention to that question, and earn for the university a place among the modern leaders of space exploration.

Launching into a new era

ASU had secured the meteorite collection. Now it needed someone to manage it, grow it and turn ASU into a leading center for meteorite research.

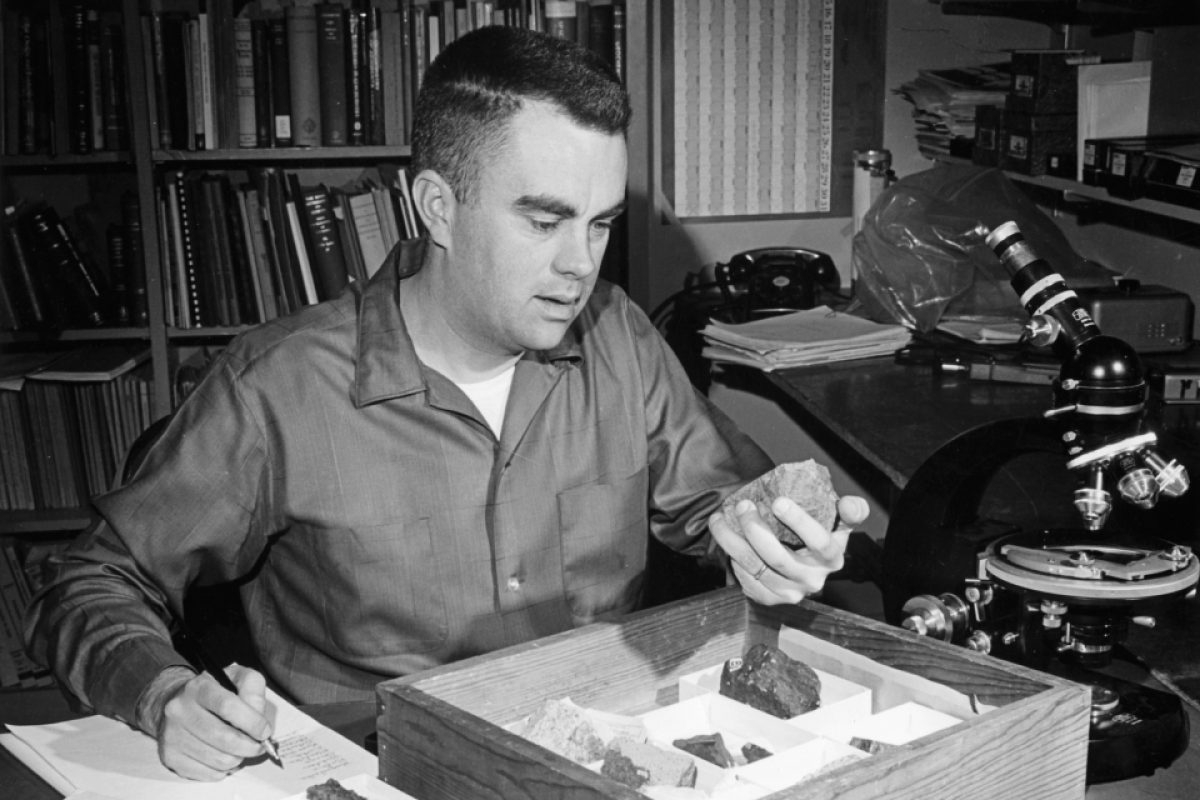

As one of the few serious meteorite researchers of that era, Carleton Moore had become aware of Nininger and his meteorites during the 1950s while studying at the California Institute of Technology. When the collection was moved to ASU, the university recruited Moore to create and lead the Center for Meteorite Studies.

“I think it represented a chance to start something new and explore this area of research at a university that recognized its value,” says Robert Moore, Carleton’s son. “It was an exciting, forward-looking opportunity for him.”

Moore set to work analyzing the meteorite samples, convening research symposia and arranging a system to loan meteorites to qualified scientists around the country. His success would put him, and ASU, in the middle of one of the most monumental scientific missions in human history.

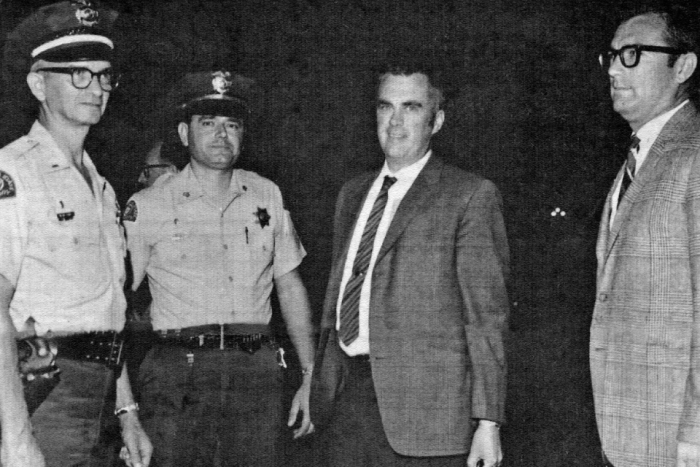

On the evening of Oct. 1, 1969, Moore was on a commercial flight at Phoenix’s Sky Harbor Airport. It taxied toward the terminal and slowed to a stop, waiting for the airstairs to approach.

With Moore was Everett Gibson, ’69 PhD in chemistry, his former student now working at NASA. They were traveling, they hoped, somewhat anonymously.

But as the passengers started collecting themselves, Gibson recently recalled, the pilot’s voice crackled through the cabin.

“Everybody, go back to your seats and sit down until the law enforcement officials come on board the aircraft,” Gibson remembers the pilot saying.

He and Moore glanced at each other.

“Carleton said, ‘OK, we’ve been had,’” Gibson says.

ASU police officers boarded the plane and escorted Moore and Gibson to a waiting vehicle. They weren’t in trouble. Moore and Gibson had with them objects of such intense curiosity and importance that ASU felt they needed to be protected.

They carried from Houston to ASU rocks and dust from the moon, samples that had come to Earth on Apollo 11 a little over two months before. Moore had been tasked with analyzing them in his Tempe lab.

Just a few days later, late in the evening to avoid being bothered, Moore and three colleagues gathered to begin their work.

“This was a definitely pivotal moment, and a story that he recalled for our family on numerous occasions,” says Robert Moore.

NASA had tried to perform the same test and gotten no result. So they asked Moore if his team could try.

He was relieved that he got readings, because, as he said in an audio recording made in 2009, “we didn’t know” if it would work.

“I remember it in great detail,” he said. The first sample Moore and his team tested was of loose lunar dirt. When he saw that he was collecting data, he remembered thinking, “We’re in business.”

After that success, Moore would be asked to re-create his lab at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, and would analyze samples from future Apollo missions. He would conduct research, hire talented scientists and lead ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies — now named the Buseck Center for Meteorite Studies — for more than 40 years, retiring in 2003. He passed away in 2023. The meteorite collection is named in his honor.

Missions with NASA

Today, there’s a direct link between the myriad space exploration missions on which ASU collaborates with NASA — such as the Psyche Mission, led by Lindy Elkins-Tanton — and that initial decision by ASU to invest in a collection of meteorites 65 years ago.

“The collection attracts good people, and that attracts opportunities to do good science,” says Laurence Garvie, the curator of the meteorite collection. “It propels us forward.”

There are only a handful of NASA missions into deep space every decade, but because of the extensive collection of meteorites at ASU, scientists around the country can explore the solar system right here on Earth.

“We have pieces of thousands of different asteroids in our collection that we can study and that we can loan to other researchers to study,” says Rhonda Stroud, the director of the Buseck Center. “We will never visit that many individual asteroids or solar system bodies. The collection gives us direct access to the variety of asteroids and other rocky bodies in our solar system.”

About the writer

An Emmy Award-winning journalist who covered the White House, the Capitol and national politics for CBS News and ABC News, Bret Hovell has spent the last decade working in higher education.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…