What happens when a class has 5 teachers?

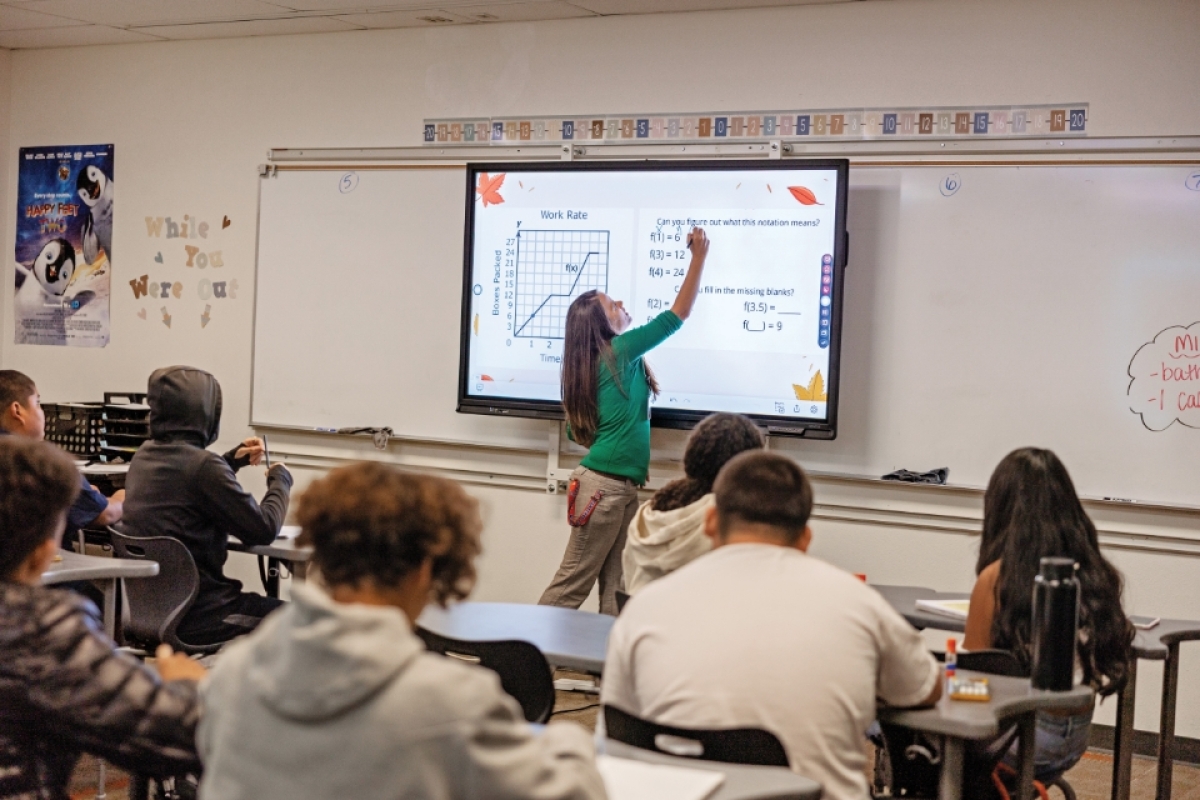

At Westwood High School, teachers work in teams. Pictured (from left) student Stockton Seaman, teacher Kelly Owen, teacher Arianna Roemke, '21 BAE secondary education (English), and student Michael Picaso. Photo by Sabira Madady

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the winter 2024 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

Westwood High School student Avery Mecham thought it was luck when she received her 2021–22 class schedule. All four of her core classes took place in a row.

It hadn’t been luck, though. It was part of a team-teaching model at Westwood High School in Mesa.

With the model, Avery spent four class periods per day — math, science, language arts and career exploration — with a mix of the same 150 students. And it meant that she and her fellow students took on more interdisciplinary projects, received more personalized help from their team of teachers and ultimately retained more of their learning.

Those benefits to students are one reason Westwood is moving to a team-teaching model.

“We recognize this is what we must do for our kids and community to improve learning outcomes,” says Westwood Principal Chris Gilmore.

A new approach

Like Avery and her mom April, Michael Picaso and his mother Cecilia, had never heard of the concept before. At first, Michael had reservations because his academy schedule didn’t allow him to enroll in orchestra as his elective.

“They put him in band instead of orchestra,” Cecilia says. “But once we figured out the timing of the classes and how they all fit together, then I understood.”

Stockton Seaman and his dad Jared, felt familiar with the concept; Stockton’s cousins had been part of that model.

“My cousins hadn’t said anything bad about it, so I just thought it was going to be fun and different — a new thing to try,” Stockton says.

How the team-teaching model came about

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College Dean Carole Basile and a team of faculty and staff developed the model in collaboration with Arizona school districts, like Mesa Public Schools, to solve some of K–12’s most pressing problems, including teacher shortages, low high school graduation rates and poor learning outcomes.

Through its Next Education Workforce initiative, the college works with schools to implement classroom models in which two or more licensed educators teach a shared roster of students. It contrasts with the traditional model of one teacher per classroom where the lone teacher attempts to work with as many as 30 or more students simultaneously.

The team-teaching framework is customizable, with each school molding the practice to fit the needs of its students. The work is part of — and leading — a national movement in strategic school staffing solutions referenced as a success by Education First, a national mission-oriented policy organization, and other education leaders.

The Westwood approach

Westwood High School administrators and the teachers college developed their team-teaching model to address two major challenges: retain educators and keep students engaged and graduating.

At Westwood, the administration divides first-year students into “academies” of 150 students. All of those students have the same teachers for their four core classes — language arts, math, science and career education. Students then go separate ways for electives.

The educators within an academy — four core teachers, all certified, experienced teachers and experts within their fields, plus one special educator — share the 150 students across four class periods and get two periods at the end of each day to take care of administrative tasks, which they divide among themselves.

“We all have our roles that align with our strengths,” says Shaun Reedy, career exploration lead at Westwood. “On my team, I am the one to go to administrative meetings and handle administrative tasks. We have a financial officer who helps look for grants to fund our projects and a data analyst who builds the class rosters based on which students might need more instruction in one area or another. Then we have two teachers that handle daily operations like scheduling.”

The educators use their prep time to plan lessons, spending half on their subject matter and the other half working as a group to plan cross-disciplinary assignments.

In some cases, the crossover means a shared theme, such as ancestry, in which the biology teacher might teach a unit on genetics and heredity while the language arts teacher assigns a paper analyzing family history. In other cases, educators work together to design projects that intertwine curriculum, such as creating a newspaper on Greek mythology; students use math to ensure their paper is profitable, language arts to write the articles and biology to explore DNA characteristics of the Grecian superheroes. And sometimes they all teach together, each explaining the part of the project most aligned to their subject area while the others help manage the classroom.

A school within a school

The Westwood Academy teachers divvy up each day’s four learning hours to best help students achieve their learning outcomes.

“So, if we see students are having trouble grasping a math concept or biology needs 90 minutes to do a lab experiment, we have the ability to do that,” Reedy says.

That flexibility also allows for more in-depth, experiential learning in which students get real-world context for the concepts they’ve learned. For example, Michael’s academy completed a project last year centered on a made-up murder mystery. The students had to analyze DNA evidence for a biology class, calculate the killer’s height from the size of the footprints for algebra and write an argumentative essay for language arts.

“It was fun,” Michael says. “Much more fun than doing a final paper or test. And I think I retained the information better, too.”

Cecilia says Michael seemed more engaged in school than in previous years. “I enjoyed the fact that he would come home and tell me about it in such detail,” Cecilia says of the murder mystery project. “And then I kind of got involved with it because he would tell me, ‘Well, this person could have done it because of these reasons, and this person could have done it for these reasons.’ So I was there with him, trying to figure out who had done it.”

Same concept, various models

At a Tempe elementary school just 14 miles from Westwood, team teaching takes a different look and feel. Kyrene de las Manitas Innovation Academy renovated its classrooms into four “learning studios” accommodating up to 120 students spanning two or three grade levels per team.

Each studio is divided into four spaces using room dividers with a glass-walled room in the center, cutting some of the noise while still allowing clear sightlines from one space to the others. The flexible space allows for fluidity — the teachers can easily move students around based on learning styles and competencies or seating configurations for group work versus individual tasks.

Kyrene’s teaching teams consist of one lead teacher, two additional certified teachers, and two or three teacher candidates. Candidates and early career educators benefit from teaching in the same space as more-experienced educators. And that helps the students too.

Better together

Whatever the approach, it improves education, including that educators get to know their students better.

“You get a view of students you can’t get as a siloed teacher,” says Westwood mathematics teacher Tyler Hettick. “It makes a difference outside of just test scores and credits. You find out what they’re dealing with at home and their learning barriers. And then, as a team, we can wrap around them and build them up.”

Team teaching also means the educators can take time off without affecting lesson plans and feel more supported. It also makes the job more enjoyable, Reedy says.

“It’s a lot more fun this way,” Reedy says. “If someone told me I had to go back to ‘one teacher, one classroom,’ that’d be it for me. I would leave education.”

Students Avery, Michael and Stockton and their parents say they’re pleased with their experiences with team teaching at Westwood.

“With Avery, there had been a lot of trepidation about going to Westwood since most of her friends from middle school were going to a different high school,” April says. “But it was within the second or third week of school that she came home every day telling me how much she loved her teachers, how much she loved the program and how she was getting to know people better. All I ever heard from her about it was positive. She did great.”

Story by Shelley Flannery. An ASU alum, ’04 BA in journalism and mass communication, she has written for national publications such as Men’s Health, Prevention and Good Housekeeping.

More Arts, humanities and education

Pen Project helps unlock writing talent for incarcerated writers

It’s a typical Monday afternoon and Lance Graham is on his way to the Arizona State Prison in Goodyear.It’s a familiar scene. Graham has been in prison before.“I feel comfortable in prison because of…

Phoenix civil rights activists highlighted in ASU professor’s latest book

As Phoenix began to grow following WWII, residents from other parts of the country moving to the area often brought with them Jim Crow practices. Racism in the Valley abounded, and one family at…

Happy mistake: Computer error brings ASU Online, on-campus students together to break new ground in research

Every Thursday, a large group of students gathers in the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory (TeoLab) in the basement of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change building on Arizona…