Biology test first publicly available to measure understanding of 5 core concepts

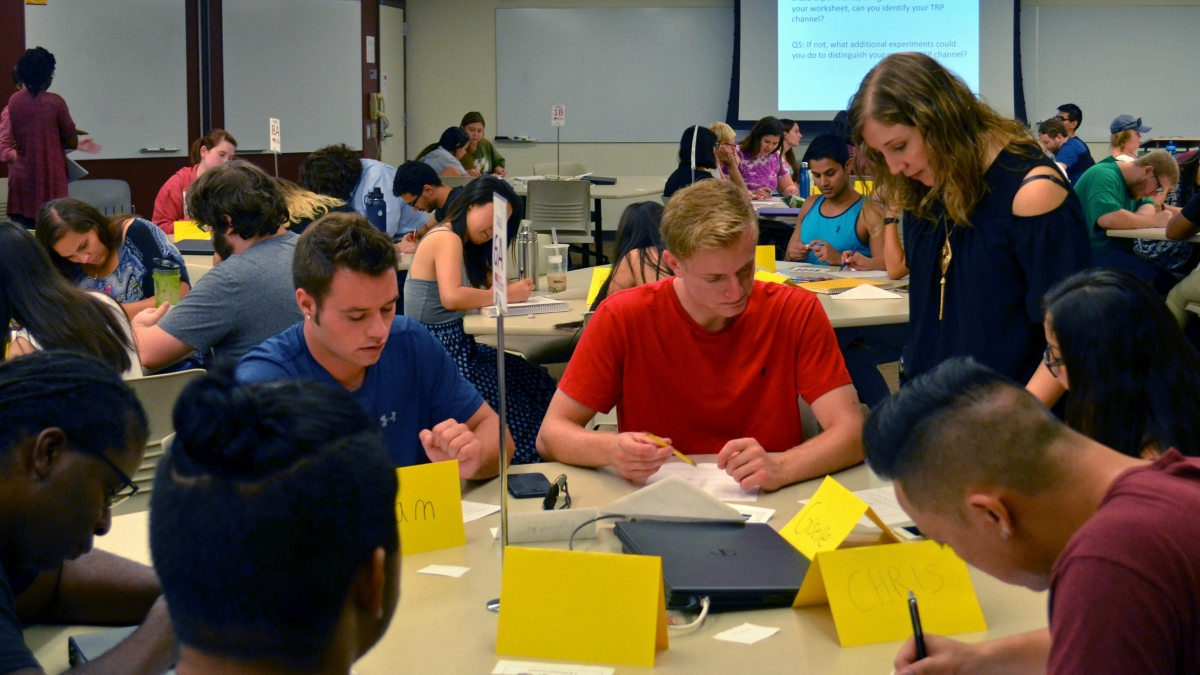

The School of Life Science's effort to improve science education includes developing ways to assess what students are learning. Because of this, a team led by ASU researchers has developed a national test to measure if students are learning core concepts through their college careers. Photo by Jacob Sahertian/ASU VisLab

Tests.

We can study for them. We can prep and practice for, cram, pass, fail or ace them.

Taking tests is one way students can find out whether they’ve learned the material taught in a particular course. But now, college biology students can find out whether they understand the five core concepts of biology: evolution, structure and function, pathways and transformations of energy and matter, information flow, and systems.

A team of researchers led by Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Associate Professor Sara Brownell and instructional professional Christian Wright have developed a first-of-its-kind comprehensive test to measure student understanding of these concepts.

This was no simple matter given how diverse the field of biology is. Test questions range from asking about molecular processes in the cell to physiological mechanisms to ecosystem dynamics.

The test, called the General Biology–Measuring Achievement and Progression in Science (GenBio-MAPS), assesses student understanding of the national core biology concepts in a way that can be used by biology departments at any type of college. And, it’s designed to measure knowledge at three separate points: before beginning the degree program, after taking general biology classes and near the end of the program. This will allow departments to track a change in learning, not just in one class but throughout the entire program.

“If you value something and you want to see it change, you have to measure it. If we really value these core concepts in biology, then we have to find a way to assess them,” Wright said. “That’s the utility of the test.”

In 2011, a national report published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science called "Vision and Change" outlined five core concepts that college biology students should learn to be proficient in biology. However, the report contained vague descriptions with few suggestions on how to implement changes or ideas to assess whether students are learning the concepts.

GenBio-MAPS, recently published in the scientific journal CBE Life Sciences Education, is already available at an online portal for any university to use free of charge. Because the test is written with multiple true-false questions, biology professors can get results the same day.

“Something that’s really cool about this test is that it can be used by any college biology department to test themselves to see how well they’re doing in teaching the core concepts,” Brownell said. “Because it is a curriculum-level test to use throughout the program, not just in one class, we can actually see whether they increase their understanding of biology in intro bio and then plateau, or whether they don’t learn anything at all across the board. And, we actually see different patterns at different institutions.”

Instructional professional Christian Wright and Associate Professor Sara Brownell led a team of researchers at several universities to create General Biology–Measuring Achievement and Progression in Science (GenBio-MAPS), the first test of its kind to measure student understanding of core biology concepts. Photo by Samantha Lloyd/ASU VisLab

To develop the assessment, Wright, Brownell and colleagues from University of Nebraska, Lincoln and University of Washington presented a variety of questions to more than 5,000 undergraduate students taking biology courses at 20 institutions nationwide. They targeted students at large research universities, liberal arts colleges and community colleges to attain a wide range of participants. Students were given an opportunity to talk through the questions as they worked on the test, so any misunderstandings in question wording could be cleared up in later versions of the exam.

All questions aim to standardize the way university biology is taught in the United States.

“A huge problem with this, as you can imagine, is that biology is so diverse,” Brownell said. “So how do you create a test that measures all students’ understanding of biology? Even within these core concepts, you can ask about each concept within different disciplines and students will think of them in a different way. Ecologists think about the world very differently than molecular biologists, but they are both under the biology umbrella.”

The researchers overcame this issue by developing questions that test multiple ideas, ensuring that students are thinking about concepts focused on specific prompts related to their disciplines.

The assessment includes a paragraph of information that presents multiple ideas that fall within the core concepts. Students must then answer a series of true-false questions about this paragraph. Previous research has shown that this is more effective than using multiple choice questions and can reveal as much as short answer questions, while also being easier to grade.

Universities can then use the data to understand the learning patterns of their students. Are students learning the concepts in introductory biology courses or in their later classes? Are there challenges that face particular demographics during the different stages? Do community college students have the same core knowledge entering the program as traditional four-year students?

It can also help answer the most pressing question: Do students learn these five concepts while obtaining their biology degree?

“Ideally, I would like to train students to be better than I was as an undergraduate. I don’t think I learned the core concepts to the extent that I needed to in my undergraduate,” Brownell said. “I want to make sure that the students I teach learn those core concepts so when they graduate, they have a much more integrated view of biology. I am motivated by the question: How are we going to create a more sophisticated biology graduate who is going to be better than we were when we graduated?”

This work was supported by a collaborative grant from the National Science Foundation Transforming Undergraduate Education in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics program.

More Science and technology

Brilliant move: Mathematician’s latest gambit is new chess AI

Benjamin Franklin wrote a book about chess. Napoleon spent his post-Waterloo years in exile playing the game on St. Helena. John…

ASU team studying radiation-resistant stem cells that could protect astronauts in space

It’s 2038.A group of NASA astronauts headed for Mars on a six-month scientific mission carry with them personalized stem cell…

Largest genetic chimpanzee study unveils how they’ve adapted to multiple habitats and disease

Chimpanzees are humans' closest living relatives, sharing about 98% of our DNA. Because of this, scientists can learn more about…