In 2010 Congress passed the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, allowing the USDA to make critical nutrition reforms to school-lunch and -breakfast programs for the first time in more than 30 years. The legislation was spearheaded by then-first lady Michelle Obama as part of her “Let’s Move!” campaign, geared toward improving nutrition in schools and reducing child obesity.

Almost immediately, the law was met with opposition, from claims that the new requirements were too difficult for schools to meet, to concerns that kids wouldn’t eat the healthier food options.

Now, a new study co-authored by Punam Ohri-Vachaspati, an Arizona State University professor of nutrition, and published by the American Journal of Public Health has found that not only are students eating the healthier food, but in some cases, school-meal participation actually increased.

“I think this paper is really timely,” Ohri-Vachaspati said. “Before other things are at stake, we need to be putting this kind of data out there. We need to say, ‘Hey, this is actually working and actually doing what we want it to do.’”

For the study, Ohri-Vachaspati and fellow researchers looked at school-meal participation rates — both breakfast and lunch — at roughly 130 low-income, high-minority public elementary, middle and high schools in four New Jersey cities from school year 2008-2009 to school year 2014-2015.

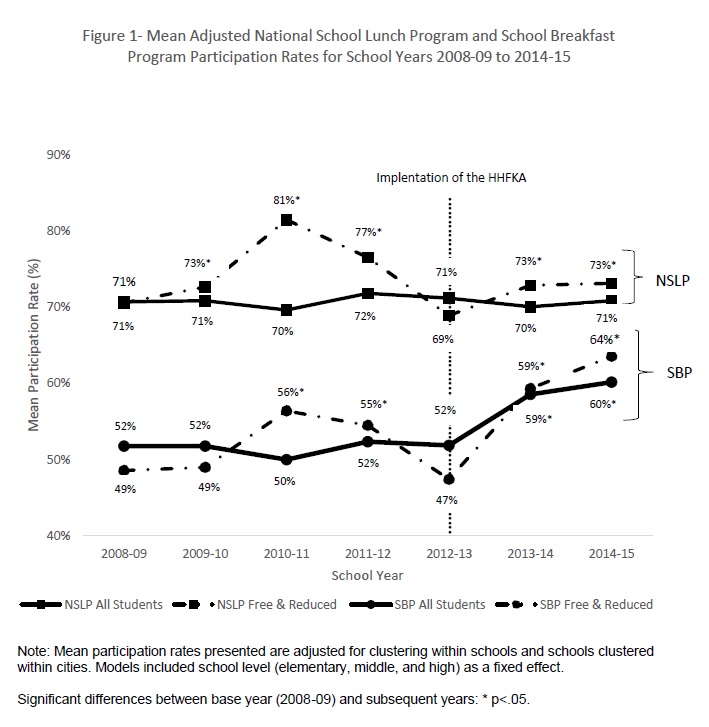

The Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act was implemented in school year 2012–2013, giving the researchers a generous seven-year window to compare school-meal participation rates, four years before the law was enacted and three years afterward.

They found that national school-lunch participation rates among students differed little over the years, increasing slightly from 70 percent to 72 percent. School-breakfast participation rates were stable from the beginning of the study period until school year 2013–2014, when they increased from 52 percent to 59 percent.

In regards to concerns that school-lunch participation would decrease as a result of the new law, Ohri-Vachaspati said, “There’s really been no change. School breakfast, on the other hand, has picked up quite a bit,” because of a provision in the law that allows schools serving majority low-income students to offer free breakfast to all students.

Ohri-Vachaspati recently returned from a yearlong sabbatical in Washington, D.C., where she saw firsthand how this kind of research influences policy.

“There’s a lot of interest in this work right now among researchers who need this kind of data,” she said. “Being in D.C., I got to see both ends of it: how policies get influenced by evidence, and also by advocacy and lobbyists.”

But Ohri-Vachaspati did far more than observe during her time in Washington. She was there as the recipient of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Fellowship, a highly competitive, rigorous fellowship for mid-career health-care professionals. It has been historically awarded to physicians; Ohri-Vachaspati became one of only a handful of nutrition researchers to be selected in the fellowship’s 42-year history.

Looking back now, she said, “I have to say that was the most transformational year in my life.”

Working in the office of Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-New York, Ohri-Vachaspati oversaw a number of assignments, including research into the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which found that in 33 out of 50 states, food-stamp participation rates are higher in rural communities and small towns.

Punam Ohri-Vachaspati (left), ASU professor of nutrition, and Sen.Kirsten Gillibrand.

So the current administration’s proposal to slash SNAP funding by billions of dollars would “hurt not just the urban poor but the rural areas and small towns as well,” Ohri-Vachaspati said.

She also worked on several pieces of legislation, two of which address other SNAP concerns: one that would allow seniors to make standard medical deductions on their income when being assessed for food stamps, and one that would allow students taking care of elderly or disabled persons to be eligible for food stamps without having to meet the 20-hour workweek requirement.

Other bills Ohri-Vachaspati contributed to include the reauthorization of the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which would provide incentives for retailers to locate in low-income areas where food desertsFood deserts are defined as parts of the country where fresh fruit, vegetables and other healthful whole foods are not readily available. are common, and a bill related to nutrition education in schools that would provide funding to states for pilot programs to integrate nutrition education into existing curriculum.

Mostly, though, she read and summarized “repeal-and-replacePresident Donald Trump has promised to repeal and replace the Obama-era health-insurance legislation known as the Affordable Care Act.” bills in time for them to be voted on.

“I spent most of my time working on [that], writing memos,” she said. “I don’t know how many memos I wrote. … Repeal-and-replace bills were introduced on almost a weekly basis, so analyzing those bills, and the speed at which you had to do it,” was a challenge.

There were several nights Ohri-Vachaspati spent working through to the wee hours of the morning. Then came time to vote on the “skinny repealThe “skinny repeal” proposed eliminating the individual mandate requiring Americans to buy health insurance, as well as the requirement for employers with at least 50 full-time employees to offer health-care coverage. ” bill.

The morning of the vote, she and others in Gillibrand’s office were “preparing for … a nightmare situation,” she said, expecting once again to be working through the night and into the next day, evaluating and making recommendations for changes to the bill.

Students from ASU had come to visit Ohri-Vachaspati, but she wasn’t able to spend time with them as she had hoped, considering the circumstances. So she boarded a train to the Capitol to send them off, and who should they see but Arizona Sen. John McCain. He recognized her student’s Diamondbacks T-shirt and greeted them warmly.

Then it was back to the office. There, Ohri-Vachaspati and her colleagues watched anxiously on TV as members of Congress settled in.

“And then came the vote. And Senator McCain comes in, and he does this,” she said, making a definitive thumbs-down sign. “And I cannot tell you the jubilation in that room — and the relief. And I never felt more proud to be an Arizonan.”

Her legacy from her time in Washington, though, are the 12 pages of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All Bill” that are hers. Title 10, section 1002 details a transition plan from our current health-care system to a single-payer plan via a public option.

Ohri-Vachaspati made trips to Canada to learn about their system and studied other countries like England and France to see what worked and what didn’t.

“It was a really interesting, collaborative process,” she said. “And to have those 12 pages embedded in there is just so cool.”

In September, Ohri-Vachaspati and colleagues at Rutgers University, where she conducted research before coming to ASU, were awarded a $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to analyze and build on an existing data set they’ve been collecting since 2008 to figure out what’s causing a decline in obesity in some populations in the U.S.

“A lot of work was being done in communities to deal with the obesity epidemic, but nobody knows which intervention is actually effective,” she said.

It isn’t the first time Ohri-Vachaspati and her colleagues have used the robust data set to assess public health policies, and she suspects it won’t be the last. It’s her passion, after all, one she discovered years ago while running a nutrition education program in Cuyahoga County, Ohio.

It was there that Ohri-Vachaspati realized public health officials have to do more than just try to change individual behavior.

“When we provided nutrition education, people love participating,” she said. “But when you looked at their behavior, there was hardly any change.”

Part of the reason was because they were working with low-income populations who lived in environments that didn’t support behavior changes, she said — it’s hard to go for a jog when you live in an area too poor to afford sidewalks or parks, and it’s hard to choose veggies over potato chips when the closest food store is a convenient mart that doesn’t stock fresh produce.

“So policy really fascinates me,” Ohri-Vachaspati said. “I’d love to do more policy-level work.”

Top photo courtesy of pexels.com

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…