'Lucy' and the origins of humans

Photo of a replica skeleton of Lucy by Deanna Dent/ASU.

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the fall 2024 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

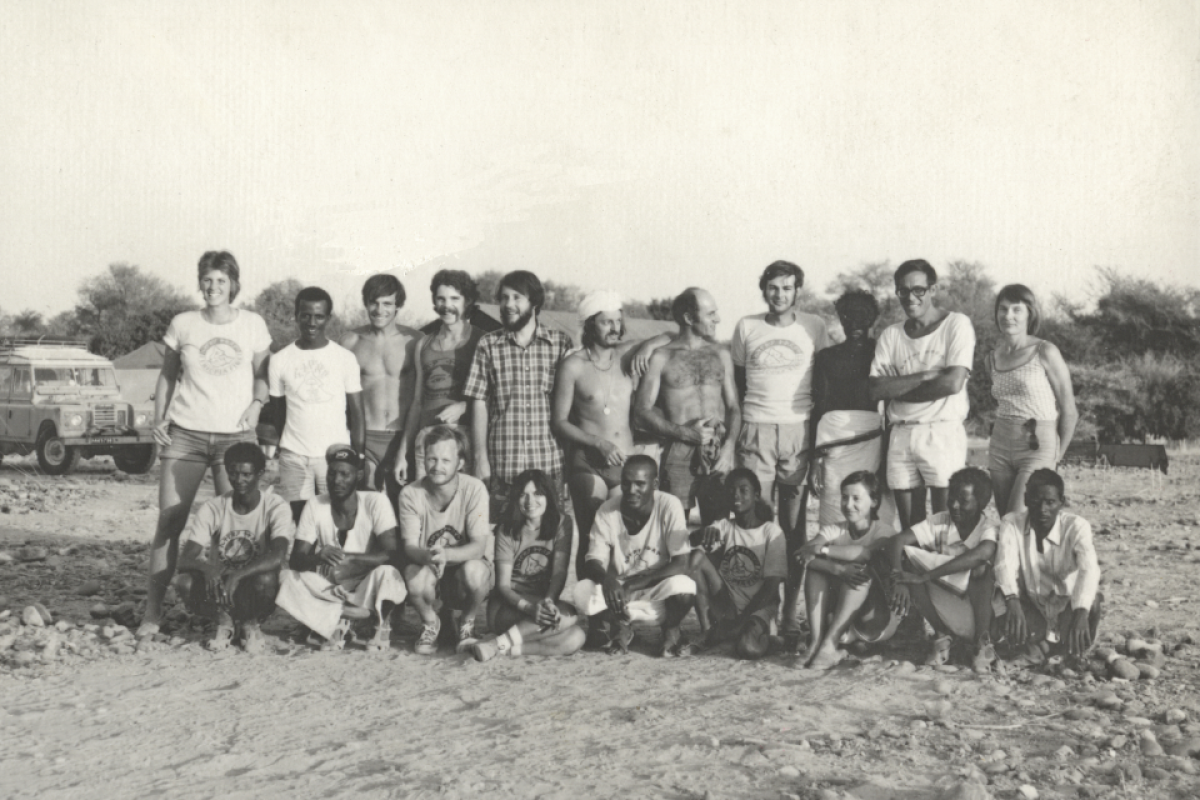

Fifty years ago, only a few years after humans’ first steps on the moon, the fossil of the first human ancestor who walked reliably upright on two feet was discovered by a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, in the dusty landscape of the Afar Rift Valley of Ethiopia.

After a long, hot morning of mapping and surveying for fossils, Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray headed back to their vehicle taking an alternative route. As he walked, within moments, Johanson spotted a right proximal ulna (forearm bone) and identified it as that of a human ancestor, a hominin.

Then he saw an occipital (skull) bone, then a femur, some ribs, a pelvis and the lower jaw. After many days of excavation, screening and sorting, the team recovered several hundred bone fragments, 47 of which represented 40% of a single hominin skeleton. Hominin refers to the zoological family Hominidae, which uses bipedal locomotion, meaning they walk upright.

What is a hominin?

Hominidae encompasses all species originating after the human/African ape ancestral split, leading to and including all species of Australopithecus and Homo. While these species differ in many ways, hominids share a suite of characteristics that define them as a group — primarily that they walk upright.

The discovery would forever change how we think of human origins.

The impact on science

Popularly known as “Lucy” because the discovery team listened to The Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” the 3.2-million-year-old fossilized skeleton remains the most complete representative of human ancestors who were adapting to life on a changing landscape.

News of Lucy’s discovery on Nov. 24, 1974, sparked a worldwide interest in human evolution and created a tremendous controversy in 1978. That’s because Lucy proved the existence of an entirely new species — Australopithecus afarensis. It changed how we think about humans’ ancestry and history on the planet.

Since Lucy’s discovery, scientists have learned that many variations of bipedal creatures thrived — and then went extinct — before and alongside Lucy and her descendants. And that these extinct ancestors didn’t necessarily start in the African savannah, but more likely roamed in grassy woodland with deciduous trees, says Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of the Institute of Human Origins and Virginia M. Ullman Professor of Natural History and the Environment in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

Lucy in the spotlight with diamonds

Explore coverage of the anniversary celebration at news.asu.edu/spotlight/lucy-at-50.

Lucy’s species survived for almost 1 million years before the pressures of environmental changes likely drove her species to adapt and evolve. Those changes paved the way for the origin of our genus Homo, which became better equipped with unique adaptive strategies, including technology.

In an April 2024 cover story in Science magazine, the article points out that “Even as paleoanthropologists debate her place in the human family tree, they agree no known human ancestor has had the impact of Lucy. They still marvel at the detailed view of our past revealed by her skeleton. Forty percent complete, it has served as a template for fitting together the isolated bones of dozens of other members of her species, like pieces in an incomplete puzzle.”

The article continues by noting that today most scientists think that 3 million to 4 million years ago, the human family tree was more like a bush than a bonsai, with multiple stems growing side by side rather than a single trunk.

Haile-Selassie “and others now see Lucy as more of a great-great-great-aunt than a direct human ancestor. But (postdoctoral researcher Zeresenay) Alemseged and others point out that so far, no other fossil is a better candidate for being the mother of us all,” according to the article in Science magazine.

Today, ASU houses a replica skeleton of Lucy, along with a model of what she might have looked like when she roamed Earth.

The lab at the National Museum of Ethiopia, where the ancient fossil bones of “Dinknesh” — Lucy’s Ethiopian name, meaning “you are wonderful” — houses the Lucy fossil, along with over 500 specimens of Lucy’s species.

Connecting the human past to the global future

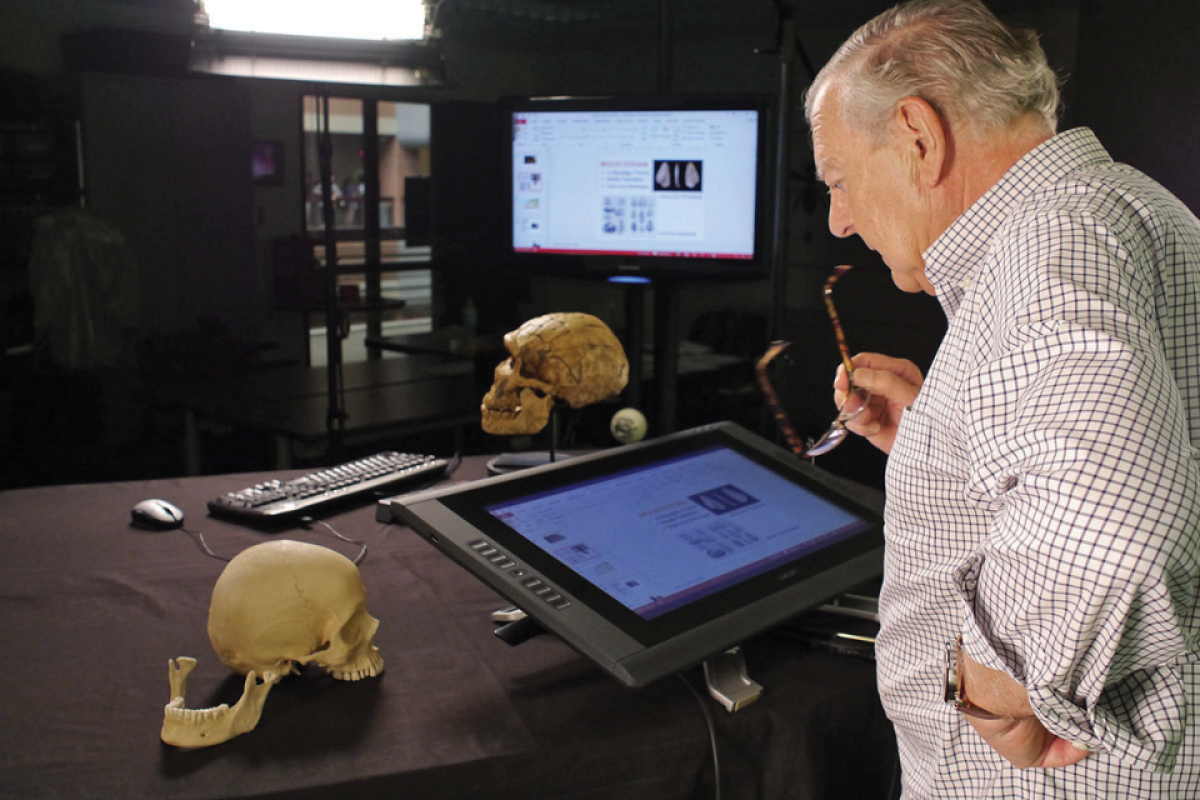

In 1997, the Institute of Human Origins, along with Johanson, moved from California to ASU. Today, the institute, part of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, is a preeminent research organization devoted to the science of human origins.

The institute’s scientists are global collaborators at the forefront of paradigm-shifting discoveries. They study how humans adapted to a changeable planet, what DNA research reveals about human origins, the genetic bases for human behavior, and how we have used our innate cumulative curiosity, ingenuity and creativity to ensure our survival and to thrive as a species.

The institute is housed in the Walton Center for Planetary Health on ASU’s Tempe campus. The building, built at an ancient crossroads, takes visitors on a journey from the ancient past to the thriving global future. Starting with the Ancient Technology Lab on the first floor, the Lucy skeleton replica and the institute on the second floor, scientists across newer disciplines work on climate challenges on upper floors.

“As stewards of Earth, we have an opportunity to actively promote a balance with nature grounded in science with an aim to protect and preserve our species and our planet’s health,” Haile-Selassie says.

Get involved

Throughout 2024, the institute is engaging ASU community members and supporters, and national and international academic and K–12 communities, with events, activities and resources.

Learn more at iho.asu.edu/Lucy50.

Read the Science magazine cover story at science.org/content/article/was-lucy-mother-us-all-fifty-years-discovery-famed-skeleton-rivals.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…