50 years later, international experts discuss importance of 'Lucy' discovery at ASU symposium

Illustration of "Lucy" species by Michael Hagelberg

“Lucy” is one of the most famous human ancestor fossils of all time.

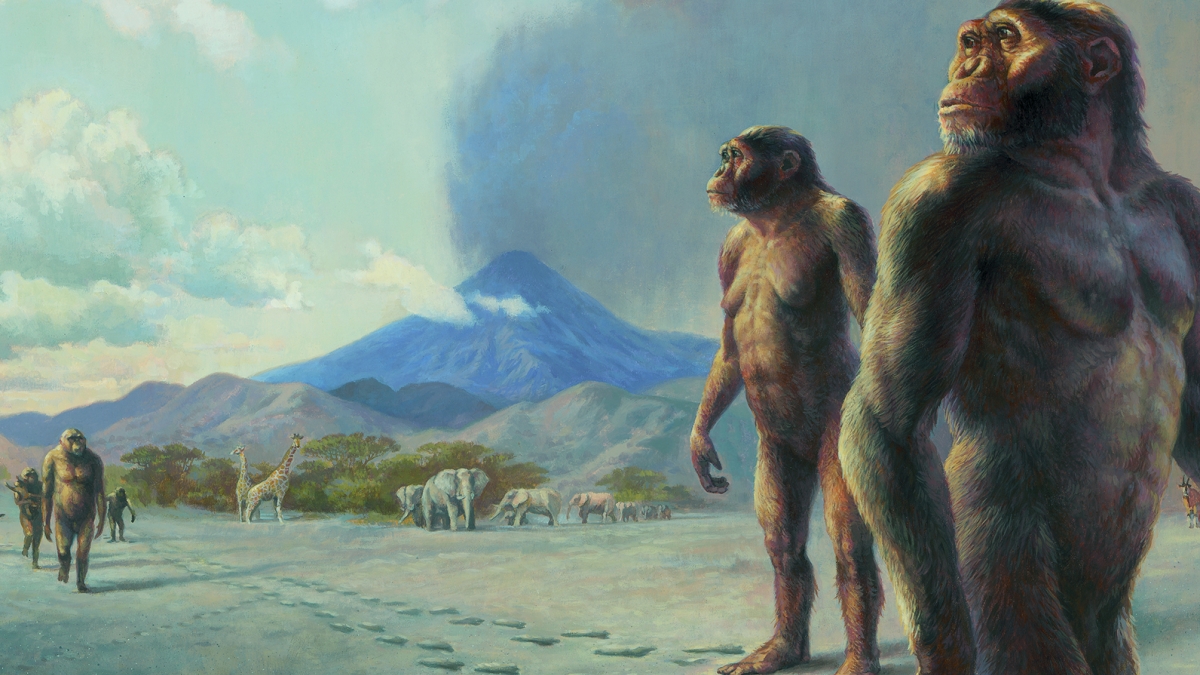

Discovered by ASU Institute of Human Origins Founding Director Donald Johanson in 1974, in the deserts of Hadar, Ethiopia, the unearthing of this 3.2-million-year-old species had a major impact on the science of human origins and evolution and on the public’s understanding of our origins. Now, 50 years later, those in the field are asking how that impact has evolved.

Lucy in the spotlight with diamonds

Explore coverage of the anniversary celebration at news.asu.edu/spotlight/lucy-at-50.

During a three-day event celebrating the 50th anniversary of this discovery, the institute gathered a group of international experts from across every field of human origins study for a one-day symposium to address this question.

Organized by Curtis Marean, ASU Foundation Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and IHO research scientist, and Yohannes Haile-Selassie, Virginia M. Ullman Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and IHO director, the event's goal was to specifically discuss the discovery’s impact through time, starting with what we knew about human origins before the 1974 discovery, its lasting impact on science, and the state of the art in that research area today.

The symposium coincided with the April 5 cover feature article, “Lucy at 50,” in the journal Science written by Ann Gibbons, who also participated in the symposium and discussed Lucy’s impact on understanding human origins science and its appeal to the public.

The article delves into the history of such discoveries — Lucy’s and those of other human ancestor species (hominins) — by a variety of human origins scientists over the past 50 years, including by the institute’s current director Haile-Selassie, who has found early hominin specimens dating back to six million years ago.

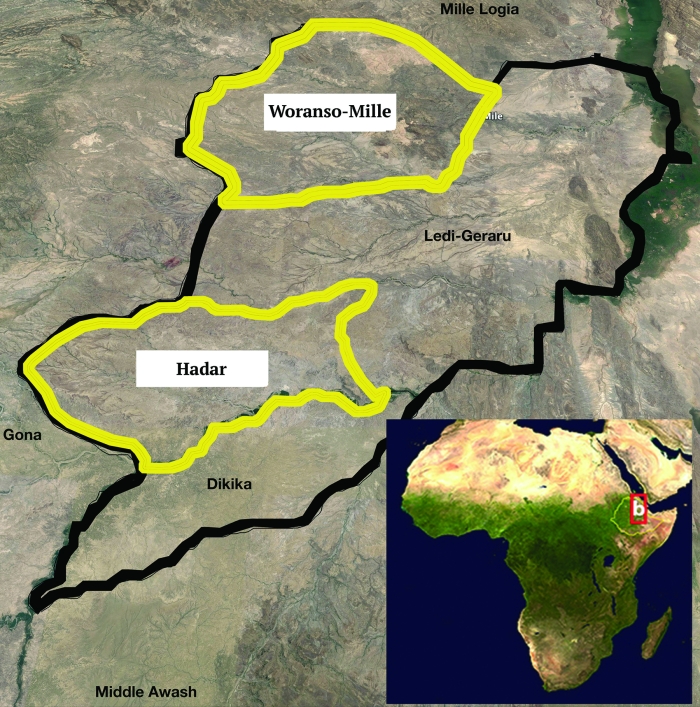

In addition to significant field sites where Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, and other earlier and later hominins were found, the article highlights the three significant Ethiopian field sites currently being investigated by institute researchers — Hadar (where Lucy was found), Woranso-Mille (Haile-Selassie’s research site where three hominin species, including the ancestor of Lucy’s species, have been found) and Ledi-Geraru (where the earliest evidence of our own genus Homo was discovered by a research team led by ASU research scientist Kaye Reed).

In the article, Gibbons highlights the significance of comparing these three sites.

“Lucy’s species was the only known hominin at Hadar — yet only 30 kilometers away at Woranso-Mille, it shared the steeper, more wooded terrain with its potential ancestor, Australopithecus anamensis, and A. deyiremeda, as well as the owner of the 3.4-million-year-old Burtele foot," she wrote. "Reed and Haile-Selassie aim to figure out why one site has so many hominins and only one at Hadar. Haile-Selassie thinks the greater diversity of habitat at Woranso-Mille may have allowed different hominins to coexist in different niches.”

The 1970s was a particularly significant time — the golden decade of paleoanthropology.

Donald JohansonVirginia M. Ullman Chair of Human Origins in ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change and founding director of the ASU Institute of Human Origins

During the thee-day event, Johanson led a discussion on the history of what was known and discovered about our human origins before those early field seasons at Hadar beginning in 1970.

Ian Tattersall, curator emeritus of the American Museum of Natural History, followed with describing what the scientific community thought about Lucy’s discovery, noting that it was a “tipping point” in paleoanthropology.

Bernard Wood, a medically trained paleoanthropologist and professor at George Washington University, reflected on comparing what researchers knew about other species in her genus and members of another related genus, Paranthropus, with Lucy — who, Wood emphasized, was and continues to be the most complete specimen of an early human ancestor ever discovered.

Andra Meneganzin, of the Kaatholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium, provided an overview on the many names of Lucy — not just “Lucy in the sky with diamonds” — and species relationships between fossils and evolutionary genetics.

We are all Lucy’s children — 8 billion people on the planet.

Zeresenay AlemsegedDonald N. Pritzker Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, University of Chicago

Understanding the 'paleoenvironment'

Not discovered until 2000 by Zeresenay Alemseged, the Dikika child, or “Lucy’s child,” was Australopithecus afarensis species and about 2.4 years old when it died. This fossil uncovered secrets of the developing brains of this species, which were about 20% larger than a chimpanzee’s.

By imaging the interior of the skull, researchers were able to determine that Lucy’s species had a longer period of brain growth — or childhood, which is a hallmark of later humans, including us.

Institute of Human Origins Research Professor Kaye Reed reviewed the effect of the “savanna hypothesis” on scientific theories about how a more open environment may have been the cause of hominin bipedality — like Lucy’s species, who were obligate bipeds.

Building on the importance of understanding the “paleoenvironment” were University of Missouri Professor Carol Ward, who discussed the interconnection of bipedality, diet and the encephalization of the brain, and Yale University Professor Jessica Thompson, who touched on the “paleo diet” of Lucy’s species, which is much different than today’s use and understanding of the term.

Tracy Kivell, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, detailed the evolution of the hand and its ability to grasp and use tools before and after Lucy.

Finally, Smithsonian Institution curator Kay Behrensmeyer focused her discussion on how Lucy became a fossil and the past and current ideas about how she may have died and been so well preserved, which is unusual for a fossil of her geological age.

By the discovery of Lucy, there was a real momentum in primate field studies to understand how these (chimpanzee) species think, behave, and interact with their environment.

Melissa Emery ThompsonDepartment of Anthropology, University of New Mexico

Reconstructing early hominin behavior

The deep past serves us as a guide to the present and our global future. The present also provides significant clues to understanding the behavior of our earliest ancestors.

Because behavior of these ancient ancestors does not fossilize, science looks to our living nonhuman primate cousins — chimpanzees — to provide clues to how cooperation and species bonding may have developed.

During the event, Emery Thompson reviewed the past and future of primate research, including that of Jane Goodall, whose Jane Goodall Institute Gombe Research Archive is now housed at ASU.

Another way researchers try to understand how these ancient species may have lived is by considering how traditional modern communities live today.

Kim Hill, an Institute of Human Origins research scientist and professor in the ASU School of Human Evolution and Social Change, has spent over 40 years living with traditional societies in South America and the Philippines and talked about understanding the sequence of steps leading to human uniqueness — how our adaptability, cooperation, and cumulative culture are the foundations of our success as a species.

Lucy’s impact on the development of African paleosciences is as important as the impact that Lucy had on our knowledge on human origins.

Yohannes Haile-SelassieVirginia M. Ullman Professor of Natural Sciences and the Environment, ASU School of Human Evolution and Social Change, and ASU Institute of Human Origins director

Teaching and learning after Lucy’s discovery

Another highlight from the symposium came from National Museums of Kenya Head of Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Job Kibii, who reviewed the history of fossil discoveries — both hominins and other animals — on the African continent by researchers from the United States and Europe, and the development of “paleodoms” by these groups of researchers, which restricts cooperation among each other and by African researchers as well.

To follow this up, Haile-Selassie highlighted the success of African countries in developing preservation and heritage guidelines and laboratories and the success of paleoanthropologist scholars in Ethiopia since the discovery of Lucy.

However, educational programs in Africa to train the next generation of paleoscience researchers has lagged behind, and most students have had to leave the country for advanced training.

To address this, Haile-Selassie suggests developing new advanced educational programs between African, U.S. and European universities.

Watch the presentations

Each of the symposium presentations can be found on the IHO YouTube channel.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…