Legal experts tackle barriers to civil justice at ASU conference

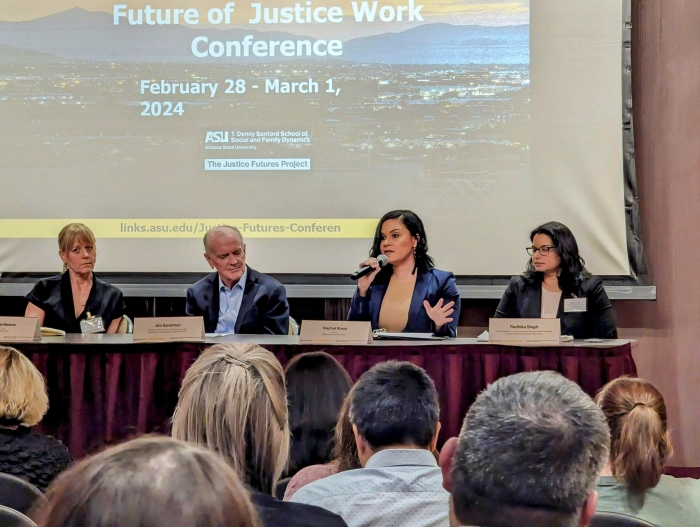

The Access to Justice and the Future of Justice Work Conference brought 150 legal experts and advocates together at ASU. Photo courtesy the Sanford School

Millions of U.S. citizens grapple with civil justice issues each year. These might be in the form of work disputes, custody battles, tenancy challenges or personal injury.

However, many individuals lack the resources or know-how to navigate their issues effectively, which can lead to outcomes in the form of lost wages, benefits or homes. In many cases, a just resolution gets left behind.

At Arizona State University's Access to Justice and the Future of Justice Work Conference, legal experts and advocates gathered Feb. 28–March 1 to challenge this status quo and explore ways to make civil justice more accessible for everyday citizens.

Attendees included supreme court justices from four different states, human rights advocates, reform and deregulation experts and other civil justice leaders. Notably, Rachel Rossi, director of the Office for Access to Justice at the United States Department of Justice, also attended.

“The exciting thing about this conference is that the future of access to justice is in our hands,” Rossi said. “It can go two different directions — it can go the path it’s been going, which is not solving it, or we can think creatively and innovatively about new ways to reduce the justice gap.”

Attendees discussed current challenges and investigated just solutions to everyday legal problems. Their focus was on creating an environment for effective and accessible justice work, empowering new kinds of justice workers and democratizing access to justice.

"What we’re after is justice for every person and every community, and the inclusion of everyone through their legal empowerment and participation in democracy,” said Rebecca Sandefur, professor and director of ASU's T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, who organized the event.

“We want to be a catalyst for the change to make those things happen," Sandefur added.

The need for approachable justice solutions

The urgency for increased access to justice is clear. Sandefur estimates there are 150 to 250 million new civil justice issues experienced by Americans yearly, with problems including legal guardianship, caretaking for the elderly, unsafe housing, unpaid benefits, getting food stamps and divorce. They affect every age and income group in society.

“These are really significant issues,” said Sandefur, a faculty fellow in the American Bar Foundation and co-founder of Frontline Justice. “They’re happening to lots of different groups, and they’re about things like making a living and having a place to live and caring for people who need you.”

Without the necessary knowledge and resources, it isn’t easy for ordinary citizens to successfully reach a just resolution on their own. Traditionally, a lawyer would be the next step. Lawyers, however, are not only prohibitively expensive for many but also unable to meet the high demand.

“The justice gap just keeps getting bigger,” Sandefur said. “Part of the problem here is that lawyers don’t scale. ... They simply can’t grow fast enough to meet 120 million new unresolved justice problems every year. So we have to start thinking about other kinds of justice solutions for all of that activity.”

Looking back to understand the future

So, what’s the solution?

Attendees discussed the most promising ideas to tackle the justice gap.

Sandefur outlined a framework called “T4” — targeted, timely, trustworthy and transparent — to meet people where they are and offer the solutions they need. In other words, people need help that is specific to their problem, available at the right time, comes from a trustworthy source and is clearly explained.

States have attempted such solutions. The state of Alaska, for example, implemented the Community Justice Worker Program, a community-led justice model that trains nonlawyers to provide limited legal aid. Since its inception in 2019, the program has trained around 300 workers with largely successful outcomes.

Several states, including Utah, have also experimented with a “regulatory sandbox” in which nonlawyers can assist citizens with civil issues without fear of repercussions. There have also been efforts to design mobile apps that provide personalized legal guidance.

Attendees also described the importance of remote legal proceedings. These allow citizens with limited transportation options or daily caretaking responsibilities, for example, to attend court sessions remotely.

Ultimately, however, bridging the justice gap at scale will require strategic collaboration, Rossi said.

“We have to use all the tools at our disposal,” she said. “We can’t just think of one solution — and that means we have to empower new voices (and) bring new people to the table. Bring the researchers, the nonlawyers, bring everyone to the table. If we do that, I think we can improve justice and reduce the justice gap.”

More Law, journalism and politics

A new twist on fantasy sports brought on by ASU ties

A new fantasy sports gaming app is taking traditional fantasy sports and mixing them with a strategic, territory-based twist.Maptasy Sports started as a passion project for Arizona State University…

'Politics Beyond the Aisle' series to explore the stories of public officials

In an effort to build a stronger connection between students and political and civic leaders, Arizona State University’s School of Politics and Global Studies hosted the first event of its new series…

ASU committed to advancing free speech

A core pillar of democracy and our concept as a nation has always been freedom — that includes freedom of speech. But what does that really mean?Higher education doesn’t have an agenda to curate a…