ASU global health student researches the importance of community-rooted birth workers in Arizona

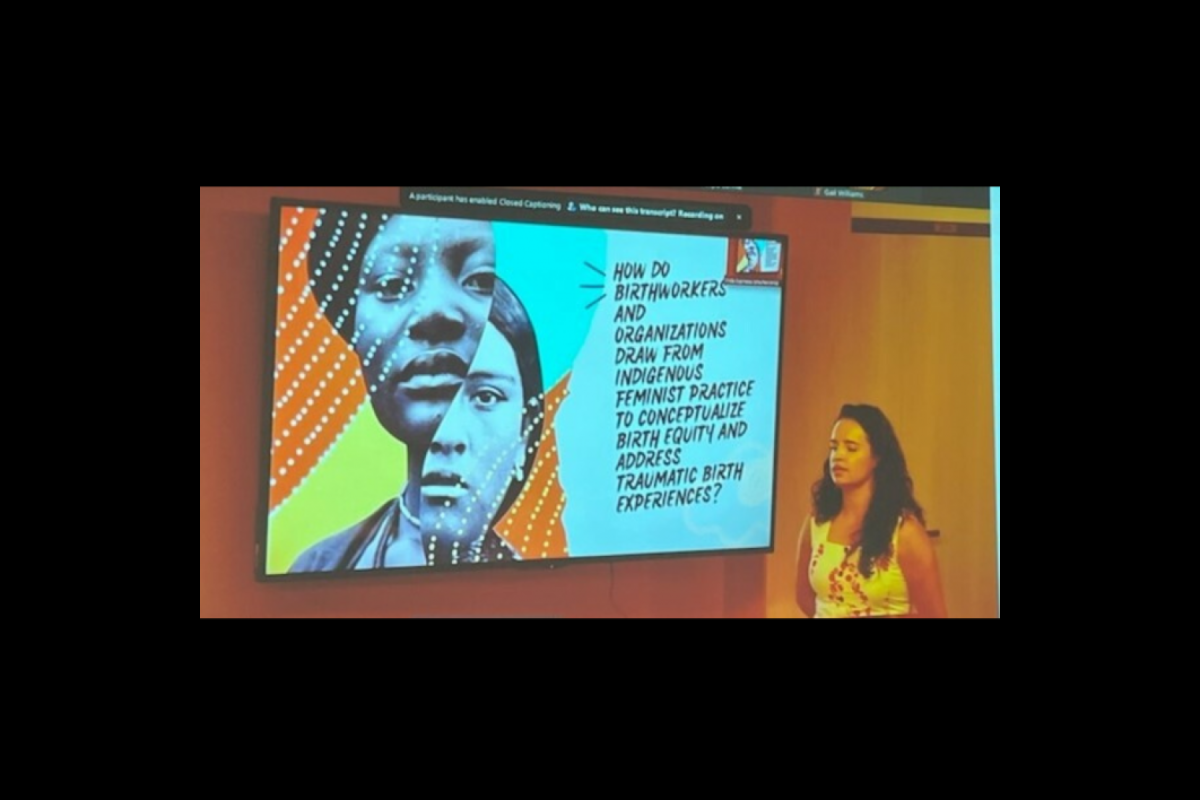

Frida Espinosa Cárdenas completed a health policy and research internship with the Institute for Medicaid Innovation. During her time in Washington, D.C., this summer, she also was a presenter at the Birth and Beyond Summit. Courtesy photo

A woman dies every two minutes from pregnancy or childbirth, according to a 2023 report from the United Nations, and up to 45% of new mothers experience birth trauma. One Arizona State University researcher is studying how ancestral knowledge and cultural practices of birth workers may help lower those numbers.

Bringing attention to maternal morbidity as a category of traumatic childbirth and the impact of colonialism in rising birth inequities is what Frida Espinosa Cárdenas’ research is about.

“Despite our technological and diagnostic advancements as providers and as public health professionals working to improve health care systems, maternal morbidity has increased,” said Espinosa Cárdenas, a global health PhD candidate with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“Between 1993 and 2014, maternal morbidity has increased by 200%, and we continue to be on this upward trend.”

Espinosa Cárdenas once was undocumented, growing up as an immigrant rights organizer during the SB1070 era, and has worked for over a decade in public health. From informing public policies to working with judges on the reunification of deported mothers and helping refugee families navigate the health care system, she has seen a lot.

With her new research, the Arizona Birthkeepers Project, Espinosa Cárdenas hopes to bring more awareness to the erasure of effective and safe, culturally grounded practices and practitioners by the biomedical system.

“My study aims to identify Indigenous feminist principles in current advocacy efforts and doula training programs in Arizona to inform a culturally restorative framework that advances birth equity policies and practices,” she said.

“As a transterritorial mother of mestiza Mexican heritage, raised on Tohono O’odham borderlands, my study allows me to engage in a reflexive research process and establish my own Indigenous feminist practice, as a scholar and member of my home communities in central Mexico, Tucson and Phoenix.”

With a background in public health, Espinosa Cárdenas hopes to bring awareness to the voices of midwives and doulas and current legislation in Arizona that can lead to increased visibility and equitable compensation for these community-rooted birth workers and knowledge keepers.

Research has shown that having doula care is one of the most effective tools to improve health outcomes and reduce racial disparities, explained Espinosa Cárdenas.

“In Arizona, severe maternal morbidity rates in Black, Indigenous and LatineA gender-neutral term for Latino. birthing people are 1.5 to 3.5 times higher than white communities,” she said. “Rates are even higher for people of color on Medicaid. Medicaid funds 47% of all births in Arizona, which demonstrates we have the opportunity to improve perinatal and birth outcomes on a large scale.”

Espinosa Cárdenas explained that she intentionally uses the term "birthing people" because not all people who give birth identify as women.

She has worked closely with the Cihuapactli Collective, a Phoenix nonprofit organization that offers the Sacred Community Birthworker Training program.

“Cihuapactli Collective embodies my heart work and now is a partner of my academic work as well,” said Espinosa Cárdenas. “Together, we are the recipients of the College of Health Solutions Maternal and Child Health Translational Research Team mini-grant, which will fund the data collection phase of my dissertation project.”

Encouraged by her elder and mentor, Patrisia Gonzales, Espinosa Cárdenas returned to her ancestral homelands for part of her research last summer. She has conducted over a dozen interviews with birth workers in central Mexico.

Her current goal is to conduct several public listening sessions and talking circles, or pláticas, to share the perspective and priorities of Arizona doulas and midwives with policymakers and birth equity stakeholders. She wants her work and information sessions to be accessible to everyone. Emphasizing her research belongs to the community and the importance of co-constructing knowledge in her work.

“The reason I center not only on gender, but Indigenous epistemologies — which is at the center of decolonial theory — is because Indigenous peoples, wherever you stand, have historically been the caretakers of the land,” she said. “So for me, it’s important to center our relationship with the land as the source of knowledge and the source of well-being and justice.”

More Health and medicine

College of Health Solutions launches first-of-its-kind diagnostics industry partnership to train the workforce of tomorrow

From 2007 to 2022, cytotechnology certification examinees diminished from 246 to 109 per year. With only 19 programs in the…

ASU's Roybal Center aims to give older adults experiencing cognitive decline more independence

For older people living alone and suffering from cognitive decline, life can be an unsettling and sometimes scary experience.…

Dynamic data duo advances health research

The latest health research promises futuristic treatments, from cancer vaccines to bioengineered organs for transplants…