Keith Harrison spent nearly three decades in a small cell in the Arizona state prison system, serving a life sentence for a crime that should have put him away for 11 years.

In November 2022, thanks to Arizona State University’s Post-Conviction Clinic, Harrison, 58, walked out of prison a free man.

The Post-Conviction Clinic is both a class and a clinic that offers pro bono legal services through the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law.

Students taking the class develop the necessary skills to investigate claims of wrongful convictions from Arizona prisoners. The six-credit class requires hundreds of hours in the clinic.

Randal McDonald, supervising attorney for the clinic, was in the courtroom the day Harrison was resentenced. He was joined by an ASU Law graduate and two law students who worked on the case.

“It was wild,” said McDonald, who teaches the Post-Conviction Clinic class. “It really was a moment to remember.”

The Post-Conviction Clinic is small — so small that the only sign that exists is a placard on McDonald's office door on ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus.

But it’s making a big difference.

Since its inception in 2009, more than 100 second- or third-year law students have taken the course.

McDonald meets with students once a week to discuss their cases. Since joining the clinic in 2021, McDonald and his students have helped seven Arizona inmates regain their freedom.

The clinic is part of the innocence movement that’s revolutionizing the criminal justice system throughout the country. Many of the cases McDonald and his students work on enable them to do what few people can — save lives.

That’s exactly what happened with Harrison.

A tough-on-crime time

In 1994, Harrison and two other men were charged in an attempted robbery. According to court records, Harrison drove alongside a truck, while the other two men jumped into the back of the pickup, pointing guns at its occupants.

Harrison and his accomplices were picked up by the police, and he was charged with aggravated assault — a crime that should have resulted in an 11-year sentence, according to McDonald.

However, Harrison’s crime occurred when an Arizona law made life sentence mandatory for anyone convicted of a felony while on parole, and he was on probation for the possession of marijuana when he was arrested.

So, the judge handed Harrison a life sentence. Harrison was 30 years old.

Then in 2020, Arizona voters passed Proposition 207, which made the purchase of recreational cannabis legal for adults 21 and older.

The initiative came with a potential get-out-of-jail provision — prisoners could petition the court to expunge or seal any of their marijuana-related criminal records, which would reduce their prison time.

The problem, McDonald explains, is that finding prisoners with charges magnified by prior marijuana convictions is not easy.

If it wasn’t for a random referral in a conversation, Harrison would still be incarcerated.

Not every inmate is that fortunate.

"That’s the biggest hurdle,” said McDonald, a Harvard Law School graduate. “We can help, but there is no centralized database. So, finding these people has been a real challenge.”

By the time McDonald reached out, Harrison had exhausted his appeals. McDonald’s helping hand gave Harrison a second shot at life.

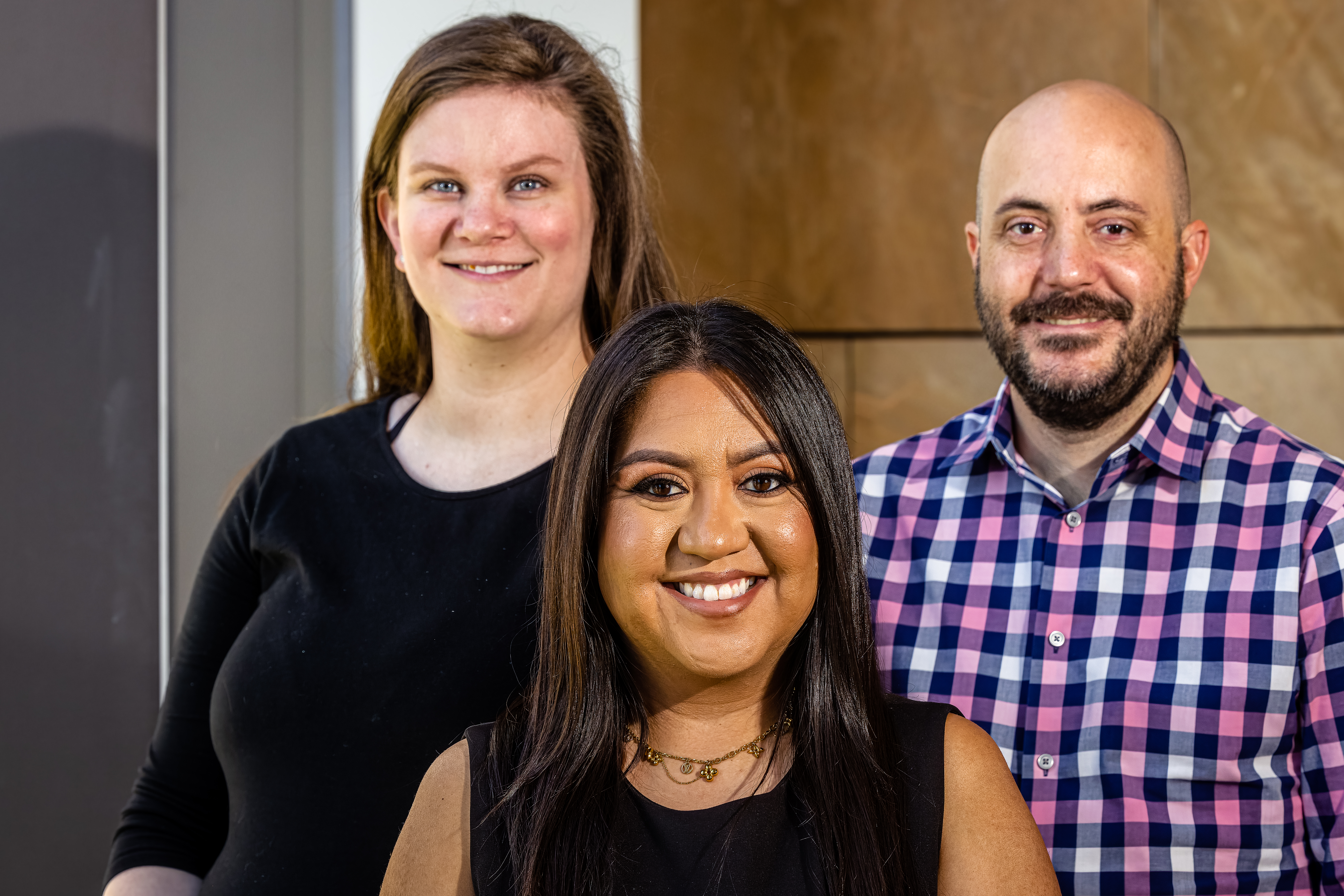

From left: ASU Law graduates Andi Humphreys and Samantha Rincon and ASU Law Professor Randal McDonald were part of the Post-Conviction Clinic effort that freed a man who was incarcerated for 30 years. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Practicing the law

The Post-Conviction Clinic is one of many ASU Law clinics that help bridge the gap between earning a degree and practicing law outside of a school setting. In the classroom, students learn the intricacies of post-conviction law and then practice what they’ve learned in the clinic.

Over the course of a semester, students will have the opportunity to collaborate with inmates, defense lawyers, prosecutors, law enforcement and investigators. They work on cases that involve everything from DNA evidence to juveniles sentenced to life in prison.

“We've worked on cases involving claims of innocence, excessive sentencing cases, cases involving prisoners in imminent danger of death, and clemency and parole cases,” said Katie Puzauskas, former supervising attorney for the Post-Conviction Clinic.

Many of the cases the Post-Conviction Clinic works on are referrals from the Arizona Justice Project — a nonprofit established in 1998 to help Arizona inmates whose claims of innocence have been disregarded. It was a grant awarded to the Arizona Justice Project that opened the Post-Conviction Clinic and grants that keep it going.

The clinic is “oftentimes the last resort for indigent Arizona prisoners who have exhausted all other appeals,” said Puzauskas, who works with the Arizona Justice Project.

Post-conviction work is a specialized, niche practice area that is becoming increasingly vital with more and more prisoners nationwide being exonerated by DNA testing and through legalized marijuana. According to NORML, a nonprofit that advocates for legalized marijuana, nearly 2 million pardons and expungements have been given to people with marijuana convictions in recent years.

Benefits for all

Andi Humphreys has been with the clinic for two years — first as a student, and now, after passing the state bar exam in October 2022, as a lawyer. Her work focuses specifically on Proposition 207 cases.

“We help people that don't have any other options," Humphreys said. "And that's very rewarding.”

When ASU Law students Samantha Rincon and Cody Jackson signed up for the Post-Conviction Clinic in August 2022, their first case was Harrison’s. The focus of their work was to get Harrison's marijuana charge dropped and then have him resentenced.

And they did.

In the process, they went through a range of motions — frustration, sadness and anger.

“Our position as law students is to turn that anger into passion for our work,” said Rincon, who graduated from ASU Law in May and will be working in civil litigation.

The work impacted both students in significant ways.

Rincon said the minute she heard Harrison’s thankful voice on the phone, “I knew that everything that I was doing had a true purpose.”

When Harrison was released just a few days before the holidays, Rincon cried.

"We take it for granted that we can spend the holiday with our family, and for the first time in nearly 30 years our client had the privilege to do so,” she said.

Both students said they were surprised on the day of the court hearing. After a couple of months of hard work, they were only in the courtroom for a couple of minutes before the judge set Harrison free.

Jackson, who is going into his third year at ASU Law, said working on the Harrison case is something he will never forget.

“This is probably one of the most rewarding experiences of my law school career,” Jackson said, “because we are able to use the skills that ASU Law gave us and work to give back to the community and help someone whom the justice system has forgotten and left behind.”

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…