ASU partnership helping students learn ‘democracy by doing’ celebrates 10 years

In the past 10 years, School Participatory Budgeting has engaged over 70,000 students from 63 campuses across Arizona school districts in direct decision-making over a portion of their school’s budget. Stock photo by Joe Davies/Pixabay

Many may assume that, given the opportunity to make decisions in their schools, students would call for things like less homework and more pizza in the cafeteria.

But not students engaged in School Participatory Budgeting (SPB) who "learn democracy by doing" and in the process understand how government officials decide public budget allocations. In the program, students deliberate and decide how to spend actual public money on projects at their schools.

The program celebrates its 10th anniversary in the United States this year. SPB is the result of a partnership between Arizona State University’s Participatory Governance Initiative, the Center for the Future of Arizona and over 60 schools in eight school districts. The process teaches K–12 students how to develop and advocate for projects within their schools. Then, students are empowered to vote on which project options will be chosen to receive actual funding provided by schools, districts or donors.

Chosen projects include building shade structures to protect those on campus from the Arizona sun and water stations that dispense purified water into reusable bottles to cut down on plastic pollution.

School of Public Affairs Professor Daniel Schugurensky, who is also director of the Participatory Governance Initiative, calls SPB “a tool that simultaneously promotes citizenship education, civic engagement and school democracy. It is an inclusive process that draws on the associative intelligence of the school community and brings more transparency and accountability to budget allocations.”

SPB comes from the municipal participatory budgeting that originated in Brazil in 1989 to involve community members in the allocation of tax revenue and has been adopted by more than 11,000 towns and cities around the world.

SPB was first implemented in the United States in 2013, when the Phoenix Union High School District began its first process with ASU at Bioscience High School in downtown Phoenix. By 2016, a partnership between the university, the center and the Participatory Budgeting Project was formed, and the process was expanded to more district schools.

Quintin Boyce, an ASU associate vice president with the university’s Educational Outreach and Student Services, was principal of Bioscience High School when the students first piloted the program. He said the process has as much relevance today as it did then.

“In democratic societies, everyone should have a place at the table and have a voice. Our schools can play a key role in preparing citizens to participate effectively in different spaces,” Boyce said. “Reflecting on the current situation of our country, SPB provides an innovative process of deliberation and collective decision-making to catalyze a lifelong venture of active engagement in our communities."

In 2018, Phoenix Union began offering SPB in all 22 of its schools, involving approximately 28,000 students. Today it is implemented in schools in other Arizona districts (Chandler, Queen Creek, Sunnyside, Roosevelt, Phoenix Elementary and Mesa), and by schools in other states like California, New York, Rhode Island and Illinois.

From 285 students a year to 70,000 today

In the past 10 years, SPB has engaged over 70,000 students from 63 campuses across Arizona school districts in direct decision-making over a portion of their school’s budget. Nearly a million dollars in public money has been invested in student-developed school improvement projects through the program. Additionally, through SPB, more than 5,700 students have been registered to vote during annual Vote Day partnerships with local elections officials and voter engagement groups.

Madison Rock, Center for the Future of Arizona project manager for civic health initiatives, expressed her organization’s great satisfaction with its involvement in SPB.

“Center for the Future of Arizona is very proud to partner with ASU (Participatory Governance Initiative) and schools across Arizona in implementing School Participatory Budgeting as a powerful strategy for engaging students to learn democracy by doing,” Rock said. “It has been thrilling to support the process as it has grown from a promising pilot here in Phoenix to a statewide initiative, which is demonstrating the power of SPB to help students become informed, equipped and empowered participants in civic life.”

Schugurensky said that SPB’s emphasis on gaining democratic competencies from participation, beyond studying or hearing lectures, comes from a long tradition in education called experiential learning.

“Like learning to swim or to ride a bike, one of the best ways to learn democracy is by doing it, not just reading about it,” Schugurensky said. “In SPB, students listen to each other and make collective decisions, and in that process acquire a great variety of civic knowledge, skills, attitudes and values, and engage in democratic practices in their schools and eventually in their communities.”

During the idea collection phase of the SPB process, students start by proposing an initial list of hundreds of items, then eliminate unfeasible options using the skills that real-life public decision-makers also use. Finally, Schugurensky said, students deliberate on the pros and cons of the selected projects, and choose their favorites by casting ballots.

Through setting budget priorities, students learn to find agreement, an important skill in our increasingly polarized society, Schugurensky said. Moreover, he said, “they learn to take ownership of their decisions, because they have to live with the consequences of those decisions.”

Tara Bartlett, education policy and evaluation doctoral candidate in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, said she was first introduced to SPB in 2015, as a teacher in the Mesa Unified School District. After implementing the process for four years, she decided to work with Schugurensky on her PhD degree at ASU and conduct research on innovations within SPB.

Students learn confidence, belonging

Bartlett said her research into schools that have implemented SPB involves interviews with students, teachers, school administrators and parents and has documented not only the projects the students chose but also intangible results, such as how participating students see themselves and their roles in society — factors she said she finds impressive.

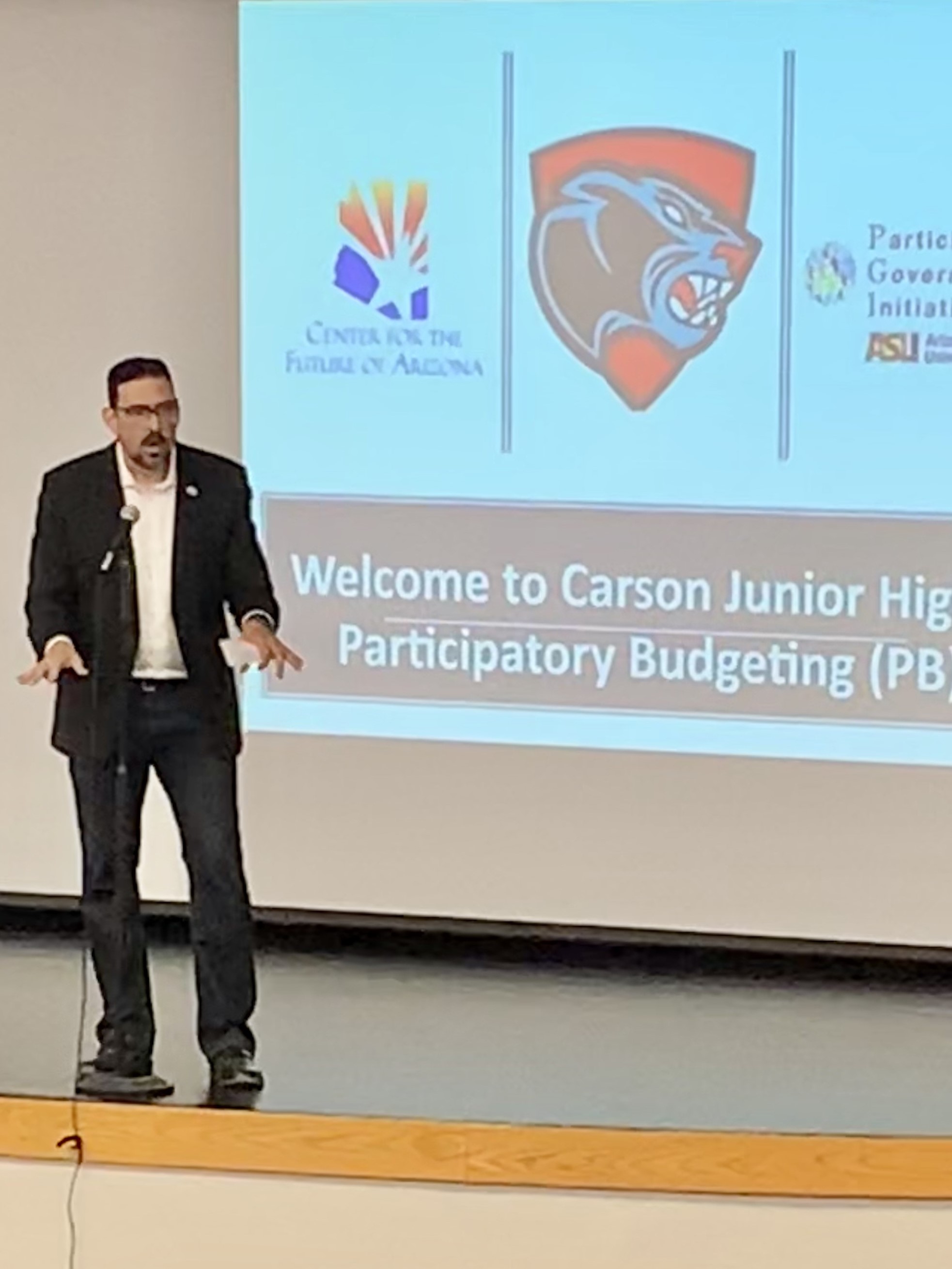

Then-Maricopa County Recorder, now Arizona Secretary of State, Adrian Fontes explains how government officials create a budget to students during an assembly at Mesa's Carson Junior High School. Photo by ASU

“Students feel they can be greater advocates for themselves and their school communities,” Bartlett said. “They report feeling more confident in public speaking and leadership skills and have a greater sense of belonging. We’re also really starting to see this kind of bleed over into each school’s climate, another unseen phenomenon that’s come of the SPB process.”

SPB encourages innovation as well as process, Bartlett said. Instead of a typical shade structure, students in a school in Tucson’s Sunnyside Unified School District partnered with the Tohono O'odham tribe to create a sustainable shade structure with elements such as wood and plant fronds. Tribal leaders will conduct a ceremony dedicating it later this year, she said.

Through SPB, many students are leading what Bartlett called the “next wave” in sustainability and climate-change education initiatives, since many of the projects they recommend involve more shade, more plants and trees, and refillable water stations. “Students are using their lived experiences, sustainability practices and concern for the environment to improve their school communities.”

Cyndi Tercero, family and community engagement manager for the Phoenix Union district, has led the implementation and expansion of SPB in her district since 2016.

She remembered retooling the SPB process during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When schools and businesses closed in March 2020 in response to COVID, district schools were in the middle of having entire student bodies vote on projects, using real voting booths borrowed from local elections officials.

“There were four or five schools that hadn’t finished,” Tercero said. “We had to scramble to figure out a way to include them.” They eventually finished balloting online.

Tercero said she is impressed by what students gain from involvement in SPB, which for many marked the first time they felt connected to their school communities.

“Some of the outcomes I see that are so inspiring, and not expected, are that our students, given the opportunity, have become so much more socially conscious,” Tercero said. “They understand the power of their voice, being empowered to say, ‘How can I make a difference in my home community as well as in my school?’”

More Arts, humanities and education

Professor's acoustic research repurposed into relaxing listening sessions for all

Garth Paine, an expert in acoustic ecology, has spent years traveling the world to collect specialized audio recordings.He’s been…

Filmmaker Spike Lee’s storytelling skills captivate audience at ASU event

Legendary filmmaker Spike Lee was this year’s distinguished speaker for the Delivering Democracy 2025 dialogue — a free…

Grammy-winning producer Timbaland to headline ASU music industry conference

The Arizona State University Popular Music program’s Music Industry Career Conference is set to provide students with exposure to…