What can be done about cynicism, hopelessness in the face of climate change?

Photo courtesy of pexels.com

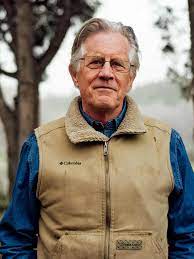

On Wednesday, Nov. 16, conservationist and writer William deBuys will be presenting a lecture titled, “Rediscovering Earth in an Age of Loss,” on the way people view and have viewed climate change and species loss over the last 50 years.

DeBuys is the author of 10 books, including his most recent, "The Trail to Kanjiroba: Rediscovering Earth in an Age of Loss,” published in 2021. He has been a Kluge Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the Library of Congress, a Guggenheim Fellow, and a Lyndhurst Fellow. He was the founding chair of the Valles Caldera Trust, responsible for administering the 89,000-acre Valles Caldera National Preserve in northern New Mexico.

This lecture is hosted by the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and the Arizona Historical Society and will begin at 6 p.m. at the Arizona Heritage Center, 1300 N. College Ave., Tempe.

Prior to the lecture, attendees can explore the Climates of Inequality exhibit at the center, which explores environmental injustices in over 20 communities and how these communities are confronting the climate crisis.

We sat down with deBuys to talk about his research and latest book.

Question: When did you first begin conducting climate research, and what brought you to this discipline?

William deBuys

Answer: I have been aware of the threat of climate change since reading Bill McKibben’s “The End of Nature” in 1989. In January 2006, however, I saw a map depicting future water woes that would afflict the Southwest and the world. The challenge embodied in the map inspired me to search out the people who made the map and find out how they reached their conclusions. That was the beginning of the research for “A Great Aridness.”

Q: The “Trail to Kanjiroba” is the third book in a trilogy that began with “A Great Aridness.” Tell us about that journey? How do these books fit together?

A: The first book, “A Great Aridness,” was a deep dive into the dynamics and probable effects of climate change in the Southwest. The second, “The Last Unicorn,” told the story of a wildlife expedition I accompanied into the remote and little-explored mountains separating Vietnam and Lao People's Democratic Republic. Our quarry was the rarest, largest terrestrial mammal on Earth, a forest browser called the saola, which looks like a beautiful, stocky antelope. We found no saola, and today the species is at the very brink of extinction, but we encountered much evidence of the ghoulish wildlife trade that provides animals and animal parts for traditional medicine practices throughout much of East Asia. “The Last Unicorn” is ultimately an adventure story and a tribute to one of the planet’s most enigmatic creatures, but it is also an account of a grisly theater in humankind’s global assault on wildlife.

After those two books, I needed renewal. I needed to answer the question, “How do we face the facts of climate change and biodiversity loss without losing heart? How do we take heart and increase our efforts to protect the beauty and splendor of the natural world?”

I hasten to add that the trilogy was unplanned. In fact I would never have had the audacity to set out on such a large project at the outset. It had to develop organically out of real and personally pressing questions.

Q: One of the striking things about “A Trail to Kanjiroba” and “The Last Unicorn” is the stunning loss of biodiversity in the past 50 years. What are the implications of that change, and how do we explain that loss to our neighbors or our children?

A: I have a young grandchild. When I am with her, I am struck by how animals dominate her books and toys, which are full of elephants, alligators, turtles and countless other species. These animals embody the wonder of the world. That’s why we delight our children with their images. Yet today, there exist only about a third of the number of wild mammals and birds that existed when I was in college. Large oceanic fish are down by 90%. And the culprit, even more than the poachers serving the wildlife trade in Southeast Asia, is the habitat loss, pollution and general rapacity of industrial civilization in which we all share responsibility. Like climate change, this is a solvable problem. We can do much better. We must.

Q: Climate change is often viewed as an exclusively policy and scientific issue; your work — especially “Trail to Kanjiroba” — brings a deep emotional connection to the problem, and the planet. Why does emotion belong in this conversation, and how might we inject human compassion into the discussion?

A: We can only meet the challenges of the future if we avoid cynicism, numbness and despair. The cynical forces that benefit from the problems beleaguering the planet would be delighted if we all sank into mindless consumerism. And, alas, far too often that’s what many of us are doing. To remain engaged and focused, to keep fighting for solutions, we have to stoke our passion for justice and for the beauty of our lands and waters. We also have to be prepared to grieve over inevitable losses and yet carry on. We can only do this as whole people, unified in body, mind and spirit. The challenges we face are not a numbers game. Reason alone will not take us through them. We have to have heart.

Q: “A Great Aridness” was published over a decade ago. Where does Arizona stand now?

A: Except for people who live under an ideological rock, everybody in the Southwest knows that water supplies are getting stretched to the breaking point and that our forests are succumbing to fires, insects and drought as never before. For a long time, climate scientists have told us to prepare for these changes, but we have done a lackluster job of heeding their warnings. Pretty much all the predictions of the climate models are coming true, except in one respect — they are arriving faster than forecast. The further truth is this: Future changes will not proceed in easy manageable increments; they will tend to snowball. The time for hemming and hawing is long past.

Q: The challenges facing the Colorado River and Arizona, specifically the increasing urban demand and declining water levels, are not unique when it comes to America’s rivers, or those around the world. Could you speak to some of the more innovative ways that communities along rivers have been responding?

A: We are going to see big reallocations of our declining water resources from agriculture to urban and industrial uses. We Southwesterners should be devoting our social energy and imagination to how we make those reallocations as equitable as possible. Here I am thinking not so much of land and water rights owners, as I suspect they will be compensated and do all right, but of farmworkers, equipment salespeople and the others, like schoolteachers, who get paid from the tax stream of the agricultural economy.

Q: In your own words, why is your research important?

A: I am not sure I can answer that question. The research is important to me personally, and I hope by sharing it, it becomes important to others. I don’t expect it to change people’s minds directly, but perhaps as one more quantum in a sea of information, something I have written might help to change the balance of social understanding. If nothing else, I am bearing witness to my world. In terms of my own interior dialogue, this is something I am obliged to do if I am to be at peace with myself.

Register to attend deBuys’ talk on the Arizona Historical Society’s website.

More Environment and sustainability

ASU event to highlight importance of urban climate research

Arizonans need look no further than their neighbor state to the west to understand why urban climate research is important.As the…

Depending on a car could be impacting your life satisfaction

A viral research study led by Rababe Saadaoui, a PhD planning student in Arizona State University's School of…

The state of water solutions

Water solutions and management must be efficient, affordable, forward-looking and leverage on innovation in order to support…