One man wants to know how his cousin died while escaping the political tyranny that overwhelmed his homeland.

A woman yearns to find out the root of the collapse of her nation’s seemingly bulletproof Air Force.

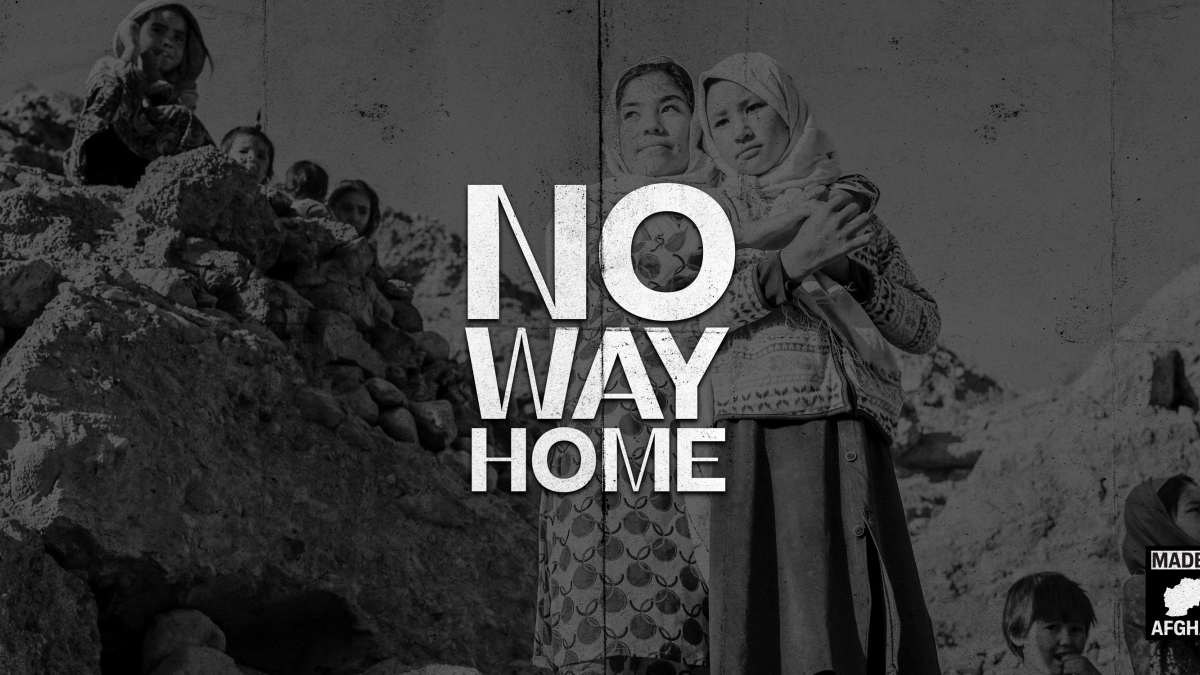

These searches for answers come to life in “No Way Home,” a four-part documentary podcast told through the lens of native Afghan storytellers who were either already outside of the country or forced to leave in the wake of the Taliban takeover in August 2021.

The podcast is a collaboration between New America and The Intercept. The Afghanistan Observatory initiative, which launched just weeks after the fall in Kabul and gives Afghan voices an opportunity to explore the tragedies surrounding the government’s collapse, provided training and editorial support for the podcast.

Candace Rondeaux

Candace Rondeaux, a professor of practice and fellow at the Melikian Center for Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies and the Center on the Future of War at Arizona State University, developed the program.

Rondeaux’s involvement comes from her role as the director for New America’s Future Frontlines program, a public intelligence service for next-generation security and democratic resilience through open source investigative tools and journalistic methods.

“The partnership with Intercept is to make sure the voices of Afghan journalists, researchers, educators and human rights defenders are not silenced and that no one at home is forgotten,” said Rondeaux during a livestream presentation hosted by New America that offered a behind-the-scenes look into the podcast, which broadcast on Sept. 15.

Rondeaux, along with Vanessa Gezari, national security editor at The Intercept, facilitated the discussion, titled “Leaving Afghanistan.”

They said the project is key to keeping the issue on people’s radars more than a year later.

“I always know that Afghanistan always gets forgotten … One motivator for us at The Intercept was to keep on this story,” Gezari said. “Being able to tell your own story in your own way, being able to ask for and seek accountability from people in power who let down 30-plus million Afghans … this can be important to healing and rebuilding your identity and your life.”

The podcast takes a deep dive into what went wrong, and the impact it had on real people.

Mir Abdullah Miri and Humaira Rahbin, Afghanistan Observatory scholars who participated in the livestream discussion, are among them.

Miri was born and raised in Afghanistan and was in Kabul for 75 days following the collapse. His work with the British government allowed for his evacuation from Afghanistan to the United Kingdom, where he is based now.

He was in a hotel room in 2021 when he got a call informing him that his cousin died while attempting to cross the border into Iran.

Miri’s story on the podcast unravels as kind of a mystery he’s aiming to solve, as he searches for his cousin’s body. He described it as a family story that allows him, as a recent refugee himself, to explore the struggles and experiences of refugees.

“I hope the podcast provides some small comfort for them and their stories are being heard,” Miri said. “This was at least a small thing I could do.”

Rahbin was in the United Kingdom, where she is currently based, with her son when the government collapsed, but worried about her husband and the rest of her family who were still in Afghanistan. She had left a month earlier, at the peak of the target killings of scholars since she and her colleagues were threatened due to their work for the Afghan government.

As the days following the fall passed, she said the tiny rays of hope she first had disappeared as the government rapidly declined.

“(I had) a feeling of shock, feeling of fear and feeling of hopelessness. … After all I accomplished and worked for in Afghanistan, my life had come down to just survival,” Rahbin said. “Slowly, I looked for opportunities to take my power back and collect all the shattered pieces of me. And then came The Afghanistan Observatory.”

For the podcast, she chose to examine the crumbling of the Afghan Air Force to investigate what went wrong, who played key roles and the impact of it all.

“I liked how (the project) really focused on storytelling. Personally, I believe in the power of storytelling, and how it connects people and how it ignites compassion,” Rahbin said.

Rondeaux realizes from personal experience that sharing trauma can be therapeutic.

In 2012, Rondeaux, who is also a journalist and public policy analyst, was in Afghanistan and wrote a piece that elicited death threats, and she was forced to leave the country quickly.

She said she wonders what the following days, weeks or months would have been like if she had had a platform like the podcast to share her experience.

“Had I been given this opportunity, I think I would've been in a different place,” she said.

“These kinds of questions are not going to be asked or answered and they should be. We’re trying to do all we can to make sure those who are responsible are not allowed to forget.”

Written by Georgann Yara.

Top photo courtesy The Intercept and Getty Images

More Law, journalism and politics

A new twist on fantasy sports brought on by ASU ties

A new fantasy sports gaming app is taking traditional fantasy sports and mixing them with a strategic, territory-based twist.Maptasy Sports started as a passion project for Arizona State University…

'Politics Beyond the Aisle' series to explore the stories of public officials

In an effort to build a stronger connection between students and political and civic leaders, Arizona State University’s School of Politics and Global Studies hosted the first event of its new series…

ASU committed to advancing free speech

A core pillar of democracy and our concept as a nation has always been freedom — that includes freedom of speech. But what does that really mean?Higher education doesn’t have an agenda to curate a…