ASU librarian on a mission to 'reclaim and repatriate' Indigenous knowledge

Starting this fall, students and researchers visiting ASU Library’s Labriola National American Indian Data Center at Fletcher and Hayden libraries (on the West and Tempe campuses, respectively) will have the opportunity to work with an expert in Native American and Indigenous libraries and archives.

Begay most recently worked as a librarian and archivist at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and as an archivist at Diné College. In her role with the Labriola Center, she will ensure culturally appropriate collections management and is available to work with all Arizona State University students and instructors seeking research assistance about Indigenous peoples.

Over 15 years ago, a dedicated group of Native American and non-Native American archivists, librarians, museum curators, historians and anthropologists came together to develop the Protocols for Native American Archival Materials. The best practices developed during that time tried to address the centuries of misuse and trauma that occurred with Native American and Indigenous materials.

The protocols were endorsed by the Society of American Archivists in 2018 and adopted by the ASU Library in 2019. In many places, that work to safeguard culturally sensitive materials and implement these protocols into non-Native repositories is just beginning.

Begay spoke to ASU News about her journey in libraries, archives and museums, how her theater background informs her work in storytelling and her goals for safeguarding Indigenous materials in the library collections.

Editor's note: The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: How did you become interested in working in libraries?

Answer: Like most librarians entering the field would commonly say, merely by accident. That rings true for me. Becoming a librarian was never on my radar. My passion was theater and film, and that was all I wanted to do. I needed a job to support my commute to Fort Lewis College. I saw a public library job posting for a library technician with a theater background, so I applied. I was fortunate to get that job in youth services. My sole purpose was to help youth storytellers, ages 6–17, prepare and refine their craft for the annual storytelling festival. This included getting them comfortable on stage, helping them with dictation, memorization, blocking, story analysis and so on.

My responsibilities later transcended into creating puppet shows from books, story time for the kiddos, readers theater for tweens and costume and makeup programs for teens. I enjoyed the puppet show the most because we did a whole production of it. We recorded the story with my staff as voice actors, drawing the backdrop, and trained my staff in stage blocking of the puppets. It was at that moment in my experience that I realized that libraries were not all about books. It changed my outlook on libraries and the impact they have on communities. I did go back to theater after completing my degree, but the economy was hit severely in 2008, which changed everything for me and everybody else, which resulted in me returning to libraries and going back to school to get my MBA and MLIS.

Q: How did going to library school change your perspective about working in museums and libraries?

A: The hook and grab that solidified my chosen career as a librarian and archivist was my archival courses. My instructor did a unit on culturally sensitive information of marginalized groups. The unit on Indigenous materials left me irate and hit me personally. It was infuriating to hear how Western institutions were improperly and disrespectfully administering and accessing our Indigenous traditional knowledge materials. While in grad school, I began doing my own research by examining other universities, museums and cultural institutions’ policies, catalog descriptions, acquisitions, etc. regarding Indigenous materials. Mind you, all this was prior to the endorsement of PNAAMProtocols for Native American Archival Materials. I talked with professionals at conferences about their approach ... to give this information back to the tribe it belongs to. There was none.

This also includes the ownership of our materials. It infuriated me more to hear various institutions tell me and other tribal members that due to intellectual property and institutional policies, you cannot just give (materials) back to the tribe. Due to copyright, intellectual freedom, fair use and institutional practices, tribal communities do not have a say on how our information should be accessed. Yet, Western institutions seek grants to preserve our Indigenous materials without the consultation of tribal communities ... This is another example of marginalization, racism and profitization of Indigenous culture and identity. More importantly, it is not inclusivity when institutions do not include and inform tribal communities of their information, which rightfully and culturally belongs to us. Henceforth, I made it my mission to fight in reclaiming and (helping to) repatriate our Indigenous knowledge and information, (and) also, (to) be the voice of change to library and archival practices for our materials.

Q: Before becoming a librarian, you were a theater major. How does your theater and storytelling background inform your current work?

A: Theater is not just entertainment; it brings a community together behind the stage and in the house. Theater is a teaching tool in the process of telling stories, communities learning from these stories and bringing awareness to injustices. Storytelling and oral history are integral elements to theater. The objectives and approaches of theater storytelling are parallel to Indigenous cultural storytelling. Storytelling and oral literacy are important learning fundamentals in our Indigenous way of life. For Indigenous people, we must never lose sight of this, especially in our process of evolving and continual survival in this colonial world. We must implement this Indigenous learning tool in all disciplines and allow books to be supplementary. For our youth to regain their culture, the details are not in the books, but in our oral literacy combined with guided hands-on instruction from our elders, spiritual practitioners, parents and so on. It’s a strong relationship to our community.

My stage may not be a performance venue, but my stage is libraries and archival repositories. In archives, the stories are the archival collections. Like audiences to the theater, researchers are my audience. When it comes to processing our Indigenous archive collections, my archiving processing is storytelling. I let the collections speak for themselves. Not all collections can be told through storytelling, so it's a case-by-case basis. I still apply Western archival processing, but only when it is needed. Our student worker, staff member and I are working on the reorganization of the Jean Chaudhuri papers and implementing this storytelling method. Upon my arrival, the collection was already organized in Western practice. After reviewing, it did not do justice to Jean in telling her story or its purpose. Why did Jean save all these documents? Why did the Labriola Center acquire this collection? How does this collection fit in Labriola’s mission? How will this attract and impact researchers? As an Indigenous archivist, my answer to these questions is through storytelling.

Q: You've talked about resilience and how important it is for Native American and Indigenous people to reclaim their culture and identity. How can tribal communities use archives to preserve and protect their knowledge?

A: Being raised with my Diné traditional practices and being a mother, I know firsthand the importance of preserving and protecting our knowledge. With each generation that follows and the influence of Western mainstream culture, we are losing our language and culture at a fast rate, especially for our tribal communities (that) lost our elders during COVID-19.

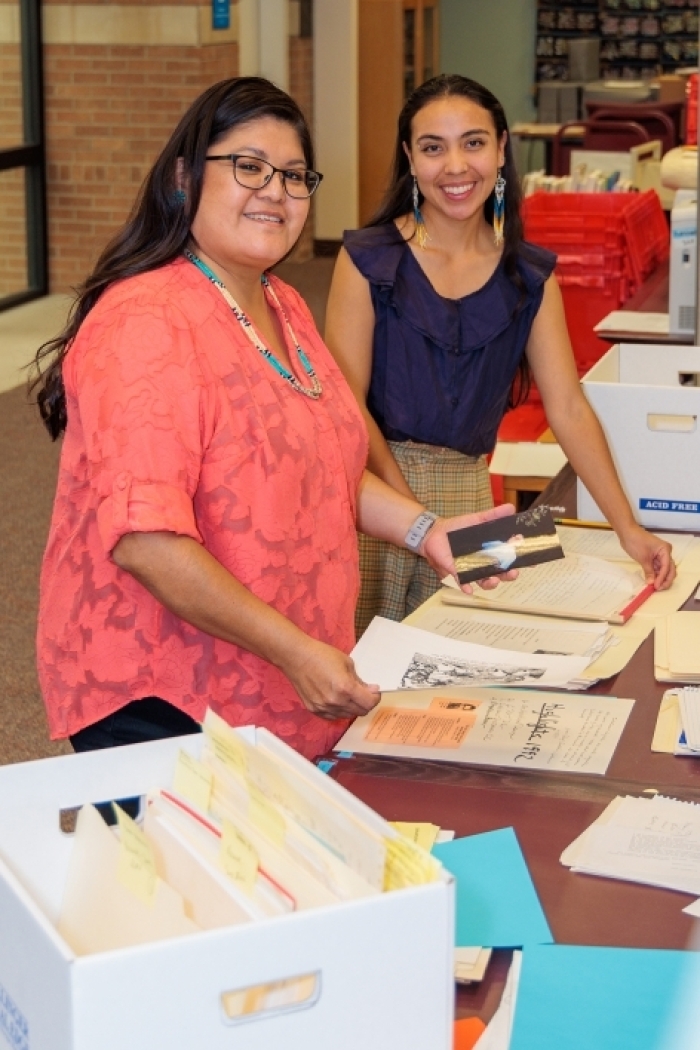

Vina Begay and Program Coordinator Yitazba Largo-Anderson at the Labriola Center in Fletcher Library on the West campus. Photo by Kyle Knox

When I train and work with tribal communities in the development of their archive centers, I provide guidance on creating the policies and procedures tailored to their cultural belief and practices. I inform tribal communities that the resurfacing of this historical information is a “blessing in disguise” towards our mission in using archives to preserve and revitalize our language and culture. These materials are our ceremonial songs, dances, prayers, creation stories and so on. The care and safeguarding of this information (is informed by) how we were taught to care for, protect and pass on our traditional knowledge. Books, video and audio recordings are foreign to our culture, but the information on these materials is what we have to protect, thus requiring us to implement these Western preservation practices for these formats. The unethical documentation of these historical materials is (still) our traditional knowledge and our elders’ voices who have passed on. It may be in books or audiovisual, but it’s still our elders’ voices.

The same applies to the cultural documentation in photographs, manuscripts, etc. I believe the resurgence of our information is our elder’s spirit wanting to be discovered and return home. For Indigenous people, we know how our songs, prayers, dances, etc. have a strong connection to our way of living and to the land. We know what is out there; now is the time to bring these home to our community to begin our healing, re-telling of our history, educating and passing our traditional knowledge – all for our community only.

Q: You also have a focus on digital archiving and accessibility. What are some of the issues when searching for Indigenous materials digitally?

A: I can discuss a lot of these issues, so I will focus on the main issue, which is description. Description, taxonomy and Dublin Core plays a crucial role in discovery of information in digital archives and information. The description of our Indigenous materials is based on controlled vocabulary, often set and based on the Library of Congress (LOC) Classification systems. The LOC subject headings do not capture or culturally describe our Indigenous materials.

I did a presentation three years ago with my colleagues from Northern Arizona University on this topic. From their collection, I took three pictures in relation to my tribe. I went to my parents, we had lunch and I asked them how they would describe each of these photographs. I took my parents description and placed it side by side to the LOC description; neither description had a connection. My parents’ description included describing objects and action in the Diné language, cultural name identifications, clanship, cultural background and sharing of traditional knowledge along the way. This disparity in description does not allow our tribal communities (to participate) in the retrieval and discovery of our information.

This not only applies to digital archives, it also applies to circulating books. It becomes difficult for Indigenous students who are looking for Indigenous materials through the library catalog and database. Believe it or not, it does impact our community, including our Indigenous students and instructors. Referring back to my parents, this was just their description. Now picture the impact on an entire collection when institutions collaborate and allow tribal communities to describe their materials. Huge impact.

Q: Your role to implement protocols for Indigenous materials is unique to the ASU Library and academic libraries. How will this support Native American students, faculty and the community?

A: First, I want to thank the ASU Library for taking this initiative in supporting and adapting the protocols. It’s an honor to be selected for this role and help drive it, yet it is a huge responsibility all together. The PNAAM is not only applicable to archives; it impacts Open Stacks, or circulated materials, Interlibrary Loan and library instructions. Professional Indigenous librarians and archivists, like me and Alexander Soto, are taking that role as traditional knowledge keepers for and in a Western institutional environment.

The protocols we implement in Labriola will help our students or faculty reconnect to their culture, such as informing our Indigenous students the reason why it's only accessible for seasonal purposes, or why only certain materials are meant for women or men, etc. These protocols also protect our traditional practicing Indigenous students and staff, including myself, from any harm when accessing information that is taboo. This has been the role and responsibility of traditional knowledge keepers and what are our elders instill within our community, especially with our youth.

On a different note, now that PNAAM is endorsed, many Western institutions are immediately incorporating the PNAAM approach ... It is one thing to say you support PNAAM, but implementing these cultural protocols in the policies and procedures is an entirely different story, especially when dealing with various tribal nations. This means incorporating various tribal cultural protocols ... Keep in mind, our Indigenous culture was never meant to be documented and was meant for our community alone.

Q: What are you most excited about for the fall semester and working with students in the Labriola Center?

A: There are so many exciting projects to look forward to, because Labriola has so much work ahead in our goal to define and show what Indigenous librarianship and archivist actually means. I love that Labriola is led by Indigenous community members and consists of a unified team with a shared vision, mission and message we want to convey regarding Indigenous information.

I am ecstatic to work with our student workers because they have an immense passion for wanting to learn our Indigenous way of librarianship and archives. They are embarking on this journey with us in paving the way and learning from us in our efforts to implement these decolonizing strategies. I am not ready to be called an elder, but that literally is what I am doing when I train my Indigenous student workers and staff, because I share the cultural dos and don’ts of documentation and determining accessibility.

Q: Is there anything we haven’t asked that you would like to share?

A: Keeping it on the topic of protocols, along with diversity and inclusivity that make up PNAAM, one of the many questions I often get asked when I talk to non-Indigenous professionals is, “How can we become a great ally to the Indigenous community?” Let me try to put this delicately and relatably: The answer is using your privilege for the greater good in support of our cause.

Look at it this way: The Bentley is the symbol of privilege and the Rez car is our Indigenous symbol. We know our Rez car can only take us so far, but we know the Bentley is what we need to get us further. A good ally will provide their Bentley and say, “Here are my keys. You’re the driver. I’m just the passenger. I'll provide the gas. If you need a plane, I can get you that plane. You lead the way, tell me where you need to be or where you would like to go.” A good ally is not about speaking on our behalf; a huge part of it is putting your own Anglo community and the colonial system in check to help us achieve our mission of equality, inclusivity and, most importantly, respecting our Indigenous way of life.

More Arts, humanities and education

Upcoming exhibition brings experimental art and more to the West Valley campus

Ask Tra Bouscaren how he got into art and his answer is simple.“Art saved my life when I was 19,” he says. “I was in a…

ASU professor, alum named Yamaha '40 Under 40' outstanding music educators

A music career conference that connects college students with such industry leaders as Timbaland. A K–12 program that…

ASU's Poitier Film School to host master classes, screening series with visionary filmmakers

Rodrigo Reyes, the acclaimed Mexican American filmmaker and Guggenheim Fellow whose 2022 documentary “Sansón and Me” won the Best…