Giant pandas show an evolutionary turn of the wrist

An artist reconstruction of Ailurarctos from Shuitangba. The grasping function of its false thumb (shown in the individual on the right) has reached the level of modern pandas, whereas the radial sesamoid may have protruded slightly more than its modern counterpart during walking (seen in the individual on the left). Illustration by Mauricio Anton

When is a thumb not a thumb? When it’s an elongated wrist bone of the giant panda used to grasp bamboo.

Through its long evolutionary history, the panda’s hand never developed a truly opposable thumb and, instead, evolved a thumb-like digit from a wrist bone, the radial sesamoid. This unique adaptation helps these bears subsist entirely on bamboo despite being members of the meat-eating order of Carnivora.

In a new paper published in Scientific Reports, researchers, including Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Denise Su and Jay Kelley, an affiliated researcher with the university, report on the discovery of the earliest bamboo-eating ancestral panda to have this “thumb.” Surprisingly, it’s longer than its modern descendants.

Uncovered at the Shuitangba site in Yunnan, China, and dating back 6 to 7 million years ago, a fossil false thumb from an ancestral giant panda, Ailurarctos, gives scientists a first look at the early use of this extra (sixth) digit — and the earliest evidence of a bamboo diet in ancestral pandas — helping us to better understand the evolution of this unique structure.

“It’s exciting that this unassuming-looking fossil is allowing us, for the first time, to understand how the panda’s false thumb evolved,” said Su, co-leader of the project that recovered the panda specimens, and a research scientist with the Institute of Human Origins and associate professor with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

Hand bones of a living giant panda. Illustration courtesy the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

While the celebrated false thumb in living giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) has been known for more than 100 years, how this wrist bone evolved was not understood due to a near total absence of fossil records.

“Deep in the bamboo forest, giant pandas traded an omnivorous diet of meat and berries to quietly consuming bamboos, a plant plentiful in the subtropical forest but of low nutrient value,” said Xiaoming Wang, lead author and paleontology curator of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “Tightly holding bamboo stems in order to crush them into bite sizes is perhaps the most crucial adaptation to consuming a prodigious quantity of bamboo.”

This discovery could also help solve an enduring panda mystery: Why are their false thumbs so seemingly underdeveloped? As an ancestor to modern pandas, Ailurarctos might be expected to have even less well-developed false “thumbs,” but the fossil Su and her colleagues discovered revealed a longer false thumb with a straighter end than its modern descendants' shorter, hooked digit. So why did pandas’ false thumbs stop growing to achieve a longer digit?

“Panda's false thumb must 'walk and chew,'” Wang said. “Such a dual function serves as the limit on how big this ‘thumb’ can become.”

“This is a prime example of the functional trade-offs that so often determine the form of structures during the evolutionary process,” said Kelley, who also co-led the Shuitangba field project and is an affiliated researcher with ASU's Institute of Human Origins and adjunct professor with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

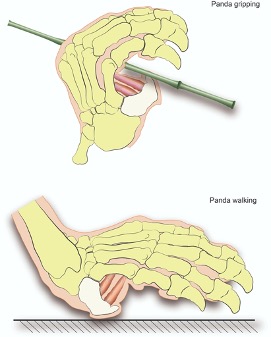

Su and her colleagues think that modern pandas' shorter false thumbs are an evolutionary compromise between the need to manipulate bamboo and the need to walk. The hooked tip of a modern panda’s second thumb lets them manipulate bamboo while letting them carry their impressive weight to the next bamboo meal. After all, the “thumb” is doing double duty as the radial sesamoid — a bone in the animal’s wrist.

Panda gripping versus walking (white bone is the false thumb). Illustration courtesy the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

“Five to 6 million years should be enough time for the panda to develop longer false thumbs, but it seems that the evolutionary pressure of needing to travel and bear its weight kept the ‘thumb’ short — strong enough to be useful without being big enough to get in the way,” Su said.

“In addition to the false ‘thumb,’” said Kelley, “a molar of Ailurarctos also found at the Shuitangba site shares the complex chewing surface of modern pandas, needed to break down tough bamboo stems.”

Authors of this article are affiliated with Arizona State University; the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County; Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; Pennsylvania State University, University Park; Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan, China; Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Kunming, Yunnan, China; and Harvard University.

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, Yunnan Natural Science Foundation, National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Governments of Zhaotong and Zhaoyang, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.

Cowritten with Tyler Hayden, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

More Science and technology

The Sun Devil who revolutionized kitty litter

If you have a cat, there’s a good chance you’re benefiting from the work of an Arizona State University alumna. In honor of…

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s…