Scientists study microorganisms on Earth to gain insight into life on other planets

Lead author Alta Howells (left), co-author Alysia Cox (standing right) and co-author James Leong (seated) take a gas sample for H2 analysis, review field notes and analyze aqueous chemistry on a spectrophotometer in Oman for this study. Photo by Kirt Robinson

In Oman, on the Persian Gulf, there is a large slab of ancient seafloor — including ultramafic rocks from Earth's upper mantle — called the Samail Ophiolite. These unique rocks not only provide valuable information about the ocean floor and Earth’s upper mantle, they may also hold clues to life on other planets.

To find these clues, a team of scientists from Arizona State University, who are members of the Group Exploring Organic Processes in Geochemistry led by Everett Shock of the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the School of Molecular Sciences, traveled to Oman to investigate a geological process unique to these rocks, where water reacts with them to create hydrogen gas. This process, called “serpentinization,” supplies hydrogen gas to microorganisms that oxidize it for energy.

For this team, gaining an understanding of this process may lead to a better understanding of life on other planets and the development of space exploration instruments that can detect life on ocean worlds beyond Earth. The results of their findings have been published in AGU’s JGR Biogeosciences, with lead author Alta Howells, who is a former ASU graduate student in the School of Life Sciences and is now a NASA Postdoctoral Program Fellow at NASA Ames Research Center. Shock is a co-author on this study.

“It is believed that processes like serpentinization may exist throughout the universe, and evidence has been found that it may occur on Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus,” Howells said.

For their study, the research team set out to determine what might influence the biodiversity of serpentinization-hosted ecosystems on Earth. Specifically, the team focused on methanogens, which are microorganisms that produce methane by oxidizing hydrogen gas with carbon dioxide. Methanogens are found in serpentinization-hosted ecosystems and are simple life forms that likely evolved early on Earth.

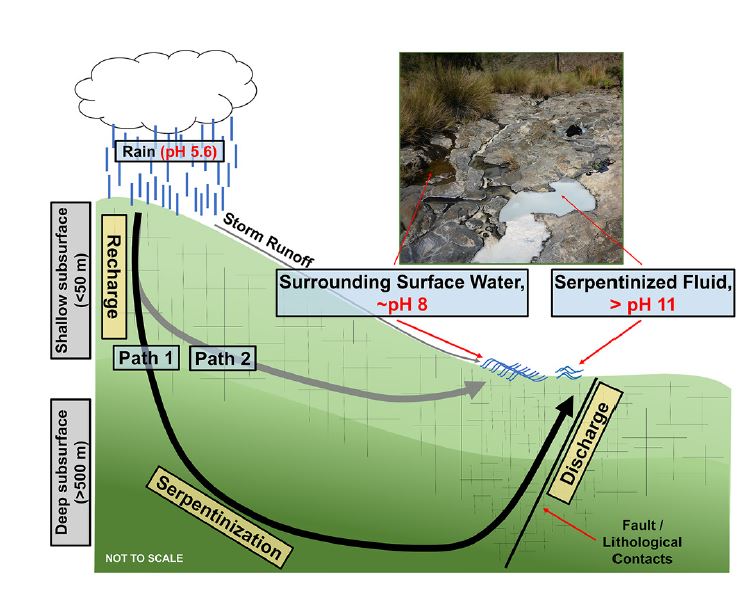

Conceptual diagram of the process of serpentinization in Oman. At the surface, serpentinized fluid, surrounding surface water, and storm runoff can mix, which results in geochemical gradients. The inset picture shows one of the sites in this study where surrounding surface water is gently mixing into serpentinized fluid. Image by Howells et al.

When studying the serpentinized fluids in the Samail Ophiolite of Oman, the team found that not all serpentinization-hosted ecosystems may support methanogens. In systems where methanogens are not supported, organisms that reduce sulfate for energy may be prevalent.

“Because sulfate reducers don’t produce methane, this can have a big influence on the instrumentation we develop and deploy on missions to detect life on other planets,” Howells said.

Additionally, from an Earth perspective, the distribution of methanogens across the sites they studied suggests that methanogens in serpentinized fluids require more energy than methanogens found in freshwater or marine sediments.

While the cause of this has yet to be determined, it may be attributed to the high pH of serpentinized fluids or the low availability of their electron acceptor, carbon dioxide.

“A requirement for energy is fundamental to all life on Earth,” Howells said. “If we can develop simple models with energy supply as a parameter to predict the occurrence and activity of life on Earth, we can deploy these models in the study of other ocean worlds.”

Additional co-authors on this study from ASU include James Leong, Tucker Ely, Kirt Robinson, Sofia Esquivel-Elizondo, Rosa Krajmalnik-Brown and Michelle Santana, with Alysia Cox of Montana Technological University and Amisha Poret-Peterson of the USDA-ARS.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…