A few months after her husband, David, was killed in the line of duty in February 2020, Kamellia Kellywood was asked to assist with COVID-19 contact tracing for the White Mountain Apache Tribe in northeastern Arizona.

Like her husband, a White Mountain Apache police officer, Kellywood had always wanted to be of service to her community, and after graduating from Arizona State University with her bachelor’s degree in healthy lifestyle coaching, she had been working with Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian Health in Whiteriver, Arizona, as a research assistant for its infectious disease team.

ASU College of Health Solutions Indigenous Health Ambassador Kamellia Kellywood and her sons, Gabriel (left) and David Jr. Photo courtesy of Kamellia Kellywood

When they pivoted to contact tracing, she jumped at the chance to help, finding a kind of solace in the work that distracted her from her grief. Sadly, it also opened her eyes to the health disparities faced by many Indigenous communities.

That experience solidified her decision this fall to accept an offer from ASU’s College of Health Solutions to be an Indigenous health ambassador.

Six other local and national Indigenous community leaders have also signed on as ambassadors for the college: John Molina, corporate compliance officer for Native Health of Phoenix; Donald Warne, director of Indians Into Medicine (INMED) and Public Health Programs, and associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion in the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of North Dakota; Myra Parker, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington; Michael Allison, retired Native American liaison for the Arizona Department of Health Services; Kim Russell, executive director of the Arizona Advisory Council on Indian Health Care; and Rear Adm. Michael Weahkee, assistant surgeon general for U.S. Public Health Service and deputy area director of the Phoenix area for Indian Health Service.

Collectively, the ambassadors will serve as advisers to the College of Health Solutions on ways to strengthen its commitment to Indigenous health, which may include but is not limited to the recruitment and mentoring of prospective or current students, staff and faculty, as well as providing thought leadership related to potential or existing programs, classes, opportunities, lecture series, initiatives or conferences.

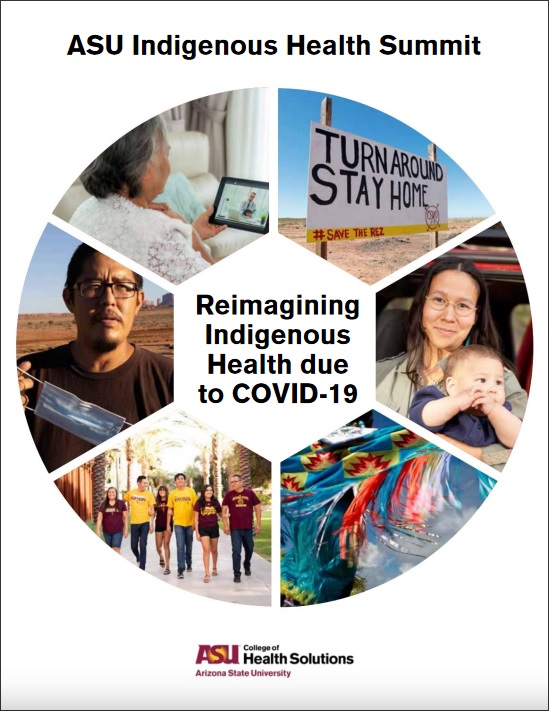

The Indigenous Health Ambassadors program is part of a grant awarded by the Tohono O’odham Nation and is one of the initiatives to come out of the College of Health Solutions’ Indigenous Health Summit, convened in January of this year in response to the disproportionate burden of illness and death experienced by tribal nations and communities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dean Deborah Helitzer, who has previously worked with members of the Navajo Nation and others on improving health conditions, said the need to address Indigenous health disparities is great, but it must be done the right way.

“The only way to know how to help communities is to ask them what they need,” she said. “Very often, people go in with their ideas and say, ‘This is what we’re going to do,’ without asking anything. They parachute in and parachute out. That’s the wrong way to do it. So we put together a summit that would bring Indigenous leaders to the table to tell us how we could use our resources and contacts at the college to help them accomplish what they need.”

This month, the College of Health Solutions released a report summarizing recommendations and detailing outcomes of the summit, including student scholarships and workshops like the 2021 Doing Research in Indigenous Communities Conference, a direct response to one of the report’s key recommendations to facilitate workshops related to data sovereignty for Indigenous communities.

Registration is required and is now open for the conference, which will take place Dec. 16 and 17, both virtually and in-person at SkySong in Scottsdale.

Nate Wade, executive director of strategic initiatives and innovation for the College of Health Solutions, has been leading the various initiatives related to Indigenous health and is serving as the principal investigator for the grant supporting the Indigenous Health Ambassadors program and student scholarships.

Last June, following a Health Talk hosted by the college that focused on the effects of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations and featured Molina as a guest speaker, Wade got a huge response from students, faculty and staff asking how they could help. He relayed the enthusiasm to Molina, and the two began laying out the plans for the January 2021 summit.

With ASU Associate Vice President of tribal relations Jacob Moore on board as co-chair of the summit with Molina, the team was ready to get to work. One of the first things they did was to identify six top challenges:

- Health disparities.

- Health system redesign — continuity and capacity.

- Health workforce of the future.

- Mental and behavioral health.

- Public health education messaging (COVID-19 vaccine).

- Telehealth/telemedicine/telepsychiatry.

“The summit was an amazing experience that shows how people of different cultural backgrounds and expertise can come together in partnership for a common purpose of improving the human condition,” Molina said.

Going forward, based on recommendations from the report, leadership intends to put efforts toward a number of issues, including:

- Increasing the pipeline of health career opportunities for tribal members, starting in early grade levels and strengthening pathways into health and science fields, with the goal of returning home to help their own respective communities.

- Increasing training in cultural competency when serving tribal communities and suggestions of a paradigm shift from a Western approach to medicine that also reflects Indigenous teaching and knowledge of healing and wellness.

- Expanding health care delivery and capacity building, especially as it relates to telemedicine, mental and behavioral health, and public health education messaging.

Kellywood says she is excited to see these various efforts come to fruition and is grateful for the opportunity to be a part of making that happen.

“When my husband wanted to become a police officer, it was because he wanted to make the world a safer place for our children,” she said. “Now I’m doing that, too.”

Top photo: A Navajo family wears face coverings and practices social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Courtesy of iStock/Getty Images

More Health and medicine

New study seeks to combat national kidney shortage, improve availability for organ transplants

Chronic kidney disease affects one in seven adults in the United States. For two in 1,000 Americans, this disease will advance to kidney failure.End-stage renal failure has two primary…

New initiative aims to make nursing degrees more accessible

Isabella Koklys is graduating in December, so she won’t be one of the students using the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation's mobile simulation unit that was launched Wednesday at Arizona…

Reducing waste in medical settings

Health care saves lives, but at what cost? Current health care practices might be creating a large carbon footprint, according to ASU Online student Dr. Michele Domico, who says a healthier…