ASU, Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation forge partnership to reclaim language

Recent years have seen a concerted effort by many in public-serving institutions to acknowledge the ancestral peoples and cultures that inhabited — and were often displaced from — the lands on which those institutions now exist.

At Arizona State University, for instance, whose four campuses within the Salt River Valley occupy land that was once home to Indigenous peoples including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Piipaash (Maricopa) Indian communities, such acknowledgements are often made before public events and even included as addendums to staff and faculty email signatures.

Tyler Peterson

While that is all heartening for ASU Professor of English Tyler Peterson, he is also aware that part of this reckoning with the history of place is the reality that among those Indigenous peoples, many of whom still live very close to the university, language loss is an ever-present threat to the preservation of their history and culture.

A trained linguist, Peterson has been working for several years with Indigenous communities across the American Southwest, such as the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, to help document, revitalize and maintain their languages.

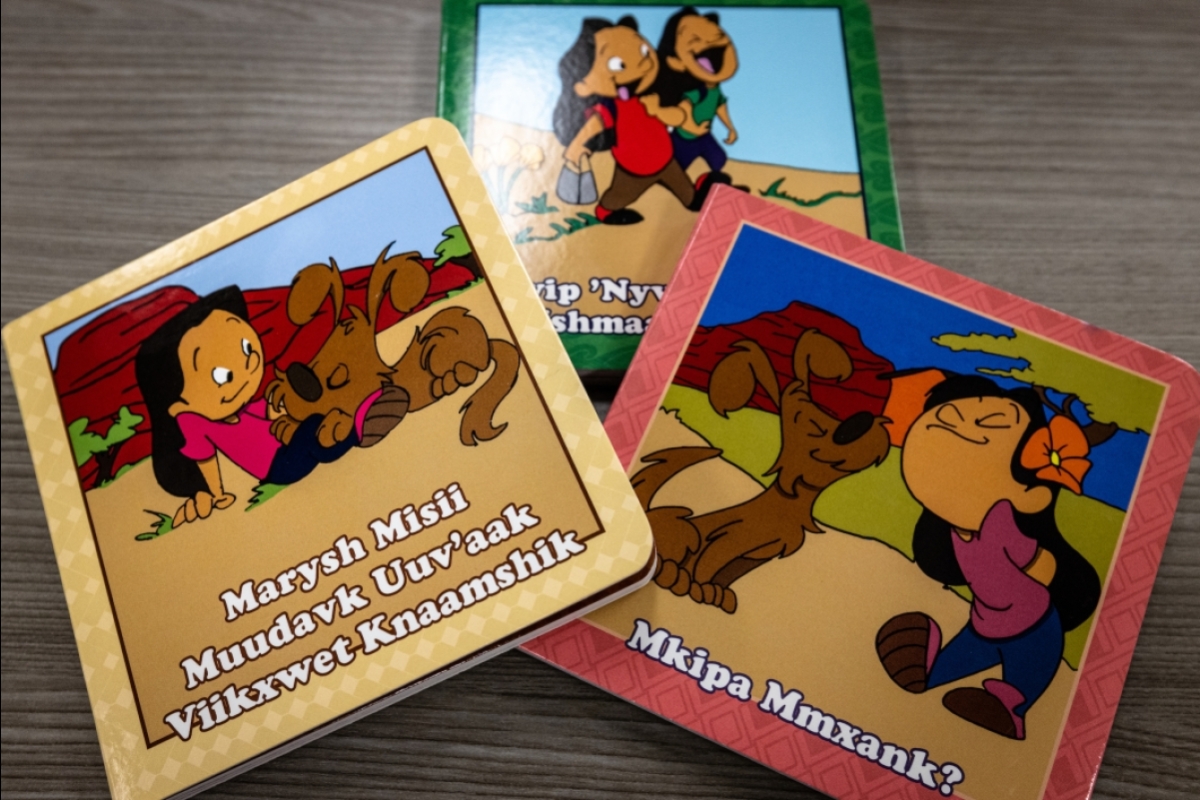

Most recently, Peterson and his colleague Jacob Moore, who is responsible for intergovernmental affairs between ASU and tribal nations and communities, oversaw the formalization of a partnership between the university and the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation Cultural Department to work on Yavapai dictionary building and the creation of a Yavapai language curriculum, among other things.

As with many Indigenous languages, Yavapai is considered to be endangered.

Jacob Moore

“There are things that go beyond language, things like positive self-identity, that are at risk,” Peterson said. “We’re just starting to understand the sort of broader social and psychological impacts of rebuilding linguistic identity.”

Peterson is quick to acknowledge that he’s not Indigenous himself, but rather “just a European dude that works at ASU.”

That said, Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation’s museum and culture department coordinator Albert Nelson thought enough of Peterson’s work to reach out to him about providing assistance interpreting legacy materials on the Yavapai language.

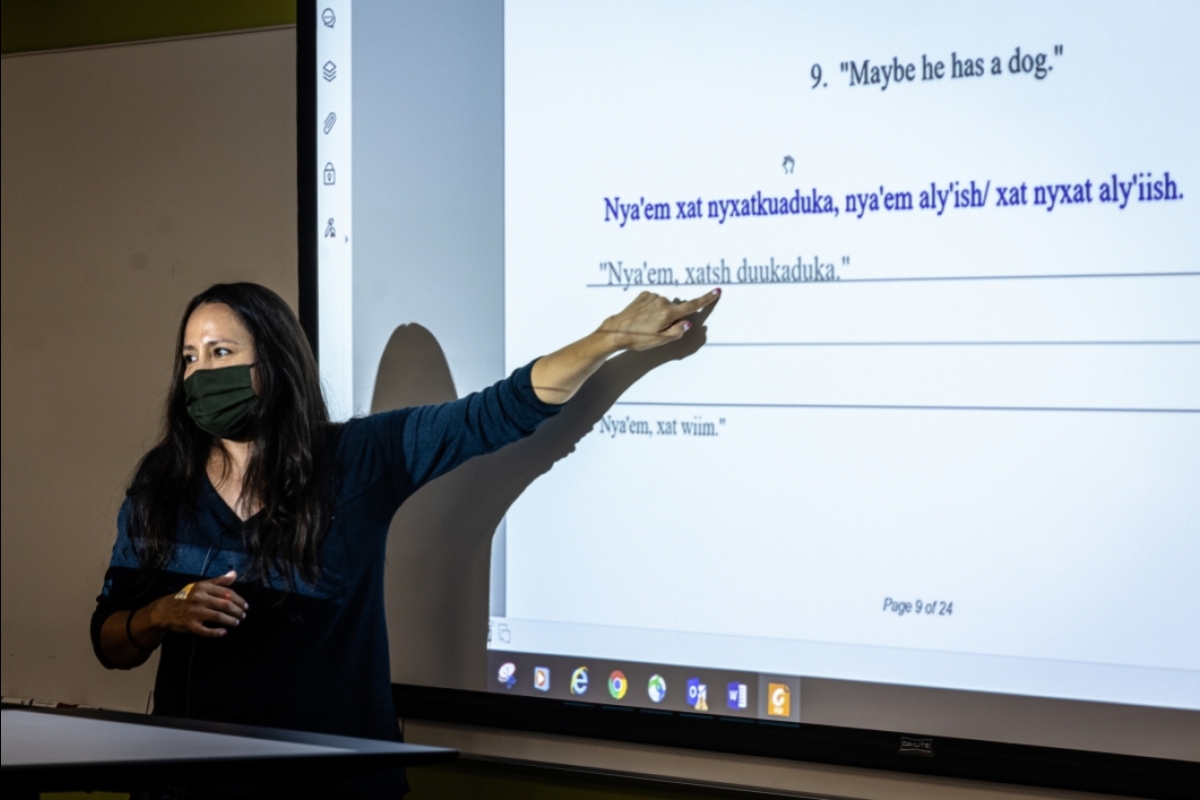

“When we're talking about legacy materials, what we mean is work that was done on the language, usually by linguists and sometimes anthropologists, that was written for an academic audience,” Peterson said. “Usually it's a dissertation or thesis; something that was done in the fulfillment of a degree.”

And while such work is extremely valuable, it’s not often easily comprehensible to those outside academia. So when Nelson reached out, Peterson happily accepted his offer to assist, designing a series of workshops with tribal members to translate the academic language of the documents into something they could work with.

Through that informal relationship, a sense of trust was built that eventually resulted in the memorandum of understanding that now exists between ASU and the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, for which Moore was essential.

“I could not have done that on my own,” Peterson said. “Nor should I have.”

Both he and Moore emphasized the importance of tribal autonomy to the agreement, especially given a long history of often non-Indigenous scholars who go into Indigenous communities to study the language only to satisfy their own scholarly pursuits, without contributing anything helpful to the communities when they leave. What Peterson hopes to do is flip that model on its head.

“There’s this idea of language reclamation, which is where the communities decide what the priorities are, and then we (academics) go in and help to build their capacity for the work they want to do,” Peterson explained. “We’re more like consultants.”

It’s also a great learning opportunity for students, who are currently working with Peterson to develop a series of workshops for the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation to train them in various methods and tools used for language documentation. In addition, Peterson is engaging professors at ASU’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College to develop a curriculum to teach the language to younger generations, a crucial element of the work.

Moore, a citizen of the Tohono O’odham Nation, noted that many individuals from older generations are still marked by their experiences in the now-infamous Indian boarding schools, where they were discouraged and even punished for speaking their ancestral language and, as a result, may not harbor as strong of a desire to preserve it.

“But the generations behind them are saying, ‘No, we do need to reclaim it. Otherwise we're going to lose it,’” Moore said. “So the fact that this young man (Nelson) has kind of taken it upon himself to begin the work of that reclamation puts them on a good path toward that end.”

Meanwhile, Peterson is continuing work on similar projects with the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community to document the Piipaash and O’odham languages. As part of ASU's inaugural Humanities Week this fall, he invited members of the community to speak to his students, who had recently completed a project transcribing stories from the languages.

Sejdina Haseljic, a fourth-year English undergraduate and a native of Bosnia, said it was an eye-opening experience.

“What I’ve learned in this class about how language diversity is declining really got to me,” she said. “Being bilingual myself (I speak Bosnian and English), I feel like it informs my worldview and helps me to be more empathetic, in a way. And I think that's so important, especially considering the brutal history of Indigenous peoples in America. I think they deserve justice for that, and maybe this work can help a little bit.”

Moore shared a similar sentiment about the idea of reciprocity.

“Fort McDowell has always been one of (ASU’s) major donors of the tribes within the metropolitan Phoenix area,” he said. “And I've always felt, what are we giving back? So I think in many ways, what Tyler and his students are doing is kind of extending that relationship so that it goes both ways.”

Top photo courtesy of iStock/Getty Images

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

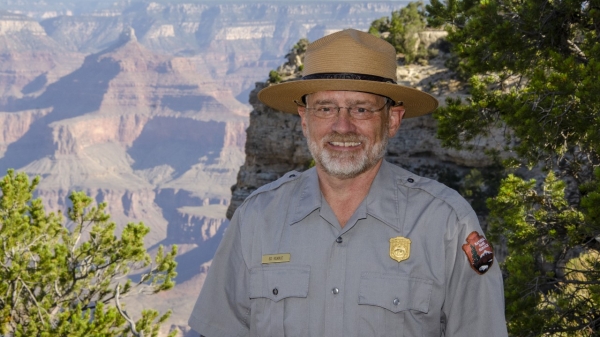

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…