Editor's note: Explicit verbal permission was given by Louise Wilson to publish photos depicting the Gitksan language.

This summer, when Peru made its first appearance at the World Cup since 1982, a daily sports program host decided to broadcast coverage of the event in Quechua, one of the country’s Native languages, spoken by their Incan ancestors. The New York Times called it “the latest move to keep a fading oral tradition alive.”

Across the globe, but especially in North America, Indigenous languages are becoming critically endangered.

“Of the hundreds of Indigenous languages spoken in North America, maybe a dozen or so will still have native speakers by the time our lives are over,” said Tyler Peterson, ASU assistant professor of English.

Generally, a language is considered to be endangered when children are no longer acquiring it.

“Language loss,” Peterson said, “is often coextensive with cultural loss, and these cultures have been decimated throughout the centuries through colonization.”

Peterson, a linguist, came to ASU in January but has been working with Native American communities across the American Southwest to help document, revitalize and maintain their languages since he came to the region about five years ago. During the spring 2018 semester, he invited students to participate in an internship where he introduced them to the scientific methodology that entails. By the summer, students were able to venture out into local Native communities and apply that knowledge firsthand.

Tyler Peterson. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

“This internship was profoundly enlightening for me,” said Rickah Dillard, who graduated in May and began her master’s degree in applied linguistics this fall. Over the summer, she worked alongside Peterson to conduct a two-week language-teacher training workshop with members of the San Carlos Apache Tribe.

Born and raised in northern Canada, Peterson, who is of European descent, grew up surrounded by the language and culture of the Gitksan, Indigenous peoples whose home territory covers roughly 20,000 square miles to the east of the Alaskan panhandle.

“Growing up, my classmates and neighbors were Indigenous people, which is also a familiar thing in Arizona,” he said.

That history and a natural love of language steered him toward the field of linguistics. At the University of Arizona’s American Indian Language Development Institute, Peterson began working with local tribes — including the Gila River Indian Community, the San Carlos Apache Tribe and the Colorado River Indian Tribe in western Arizona — conducting workshops to train community language activists in Indigenously-informed language documentation practices. Some of that work is supported by a National Science Foundation grant. After a brief stint at the University of Auckland, where he studied Cook Islands MāoriA Polynesian language spoken on a remote South Pacific island., he returned to the Southwest to continue developing the relationships he had already established in an area of the world he felt it was most needed.

“Navajo has tens of thousands of speakers,” he said. “So you might reasonably think the language is doing OK. But in fact, things are vulnerable for Navajo because the kids aren’t learning the language at an ideal rate to ensure a sustainable future for the language.

Among other Indigenous people, such as the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community situation is far more grave. When it comes to the Maricopa language, there are only about 15 speakers left.

“This is not unusual," Peterson said. "It’s striking, but it’s not unusual. With this high degree of urbanization, coupled with the historical traumas of colonization over several decades and even centuries, there are many languages in North America where there are less than 10, or even less than five speakers of many Indigenous languages.”

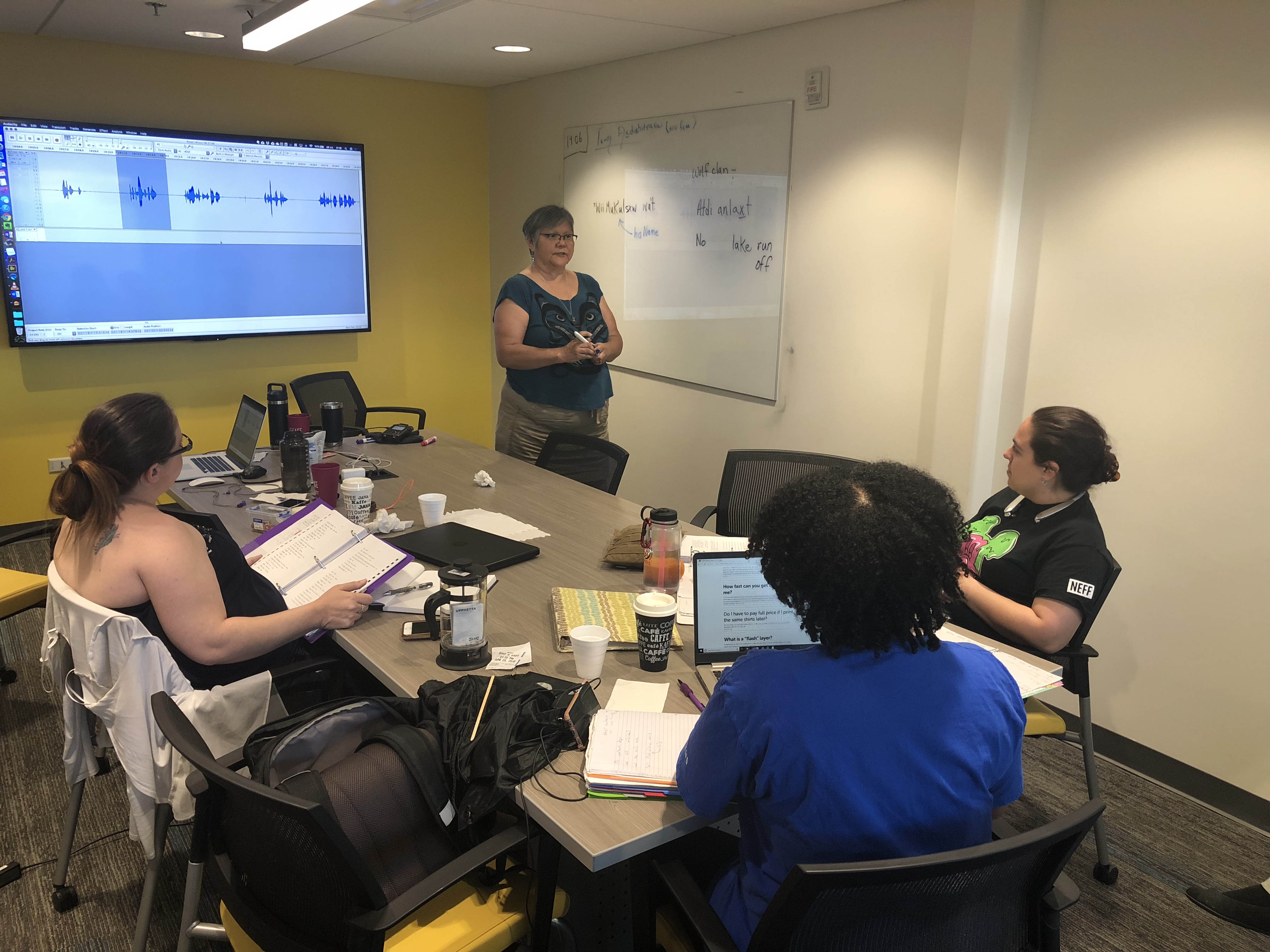

Louise Wilson, a member of the Gitksan Indigenous people of Canada, demonstrates a language point to ASU linguistics students. Photo courtesy of Tyler Peterson

Gitksan, by comparison, has anywhere from 200 to 300 speakers. One of them, Louise Wilson, came to ASU for two weeks during the spring semester to work directly with the students translating a 26-minute interview into English — writing it down, analyzing it and translating it, line by line, word by word, for hours on end.

“It’s an understatement to say they were eager and enthusiastic. They were fearless and gained confidence with every encounter in the two short weeks we spent together,” Wilson said.

Before that, students had spent four weeks learning the ins and outs of language-documentation methodology. They learned how to ask meaningful questions and use certain skills and tools to record languages that only a small number of people speak and that often aren’t written down — or, if documents do exist, are of varying quality.

“That’s a major responsibility, to document an endangered language,” Peterson said.

Students trained in how to use such tools as recording devices and transcription software, and how to navigate unfamiliar grammatical structures and sounds that don’t occur in English. They also learned how to document the meaning of words that have no concrete definition. A question Peterson likes to ask of his students to demonstrate that notion is the meaning of the word “the.”

“Everybody knows what that word is; it’s probably the most frequently used word in English,” he said.

But it’s not the same as giving the definition of something concrete, like "chair."

“That’s where things get tricky and you have to apply a very rigorous methodology in order to document meanings of things that you can’t ask direct questions about.”

ASU English Assistant Professor Tyler Peterson (left) and native Gitksan speaker Louise Wilson hold up T-shirts that say, "Team Axdiixbits’axw," which translates to "Team Fearless." Photo courtesy of Tyler Peterson

The relatively short amount of time it takes to acquire the basic skills needed for language documentation means students can get out into the community and put those skills to work quickly.

“One of ASU’s aspirational goals is to engage with the local communities and put our expertise and the university's resources in the service of our neighbors,” Peterson said. “And the local communities include the Indigenous people, the tribal people who live in this area.”

On the first day of classes in the spring semester, he was surprised when he asked his linguistics students what the local language is and confusion ensued. Then he explained that it is MaricopaMaricopa people refer to their language as "Piipaash.", the same name of the county they’re in and of the people who live within a 5-mile radius of the campus they’re on.

He hopes that sharing and involving ASU undergrads in the work and research he does with those communities outside of class will help to raise that awareness. And though he says those workshops and training sessions are just “a little tiny piece” of the effort it will take to maintain and revitalize Indigenous languages, it’s more about spreading the attitude that it matters.

“Beyond just communication, the transmission of ideas, language transmits culture and can even teach us about how the brain works,” Peterson said, referring to the field of neurolinguistics, which explores the relationship between language and the structure and functioning of the brain.

“If you think of what language does, it’s arguably the most important thing we do as humans,” he said. “It defines us.”

Top photo: A student in Tyler Peterson's Indigenous language internship transcribes a recording of Gitksan, an Indigenous language of Canada. Photo courtesy of Tyler Peterson

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU English professor wins NAACP Image Award for fiction

Nnedi Okorafor can’t imagine writing a book that wasn’t personal to her.In fact, Okorafor, a professor of practice in Arizona State University’s Department of English, knows she wouldn’t be…

A loaf of bread, a sense of community

It’s just past 8:30 on a Wednesday morning and already more than 50 people are in line waiting for Barrio Bread bakery in Tucson, Arizona, to open.The doors to the bakery, located just east of…

ASU Gammage unmasks new Broadway season with return of 'Phantom of the Opera'

ASU Gammage has unveiled its 2026–2027 Desert Financial Broadway Across America-Arizona Broadway season with a dynamic blend of Tempe premieres, beloved classics and acclaimed new hits.It’s launching…