The ASU Art Museum is opening a new social justice exhibit on Friday in which 12 artists have created new works that explore the tragedy of mass incarceration.

“Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration” will run through Feb. 12. The show is the first one ever to take over the entire ASU Art Museum space.

The museum began working on the project three years ago when it received a grant from the Art for Justice Fund, according to Miki Garcia, director of the museum.

“I would say that this is the most ambitious and largest exhibition the museum has ever endeavored, and it’s in the midst of Black Lives Matter protests and of the museum seeing itself as a champion of the community’s well-being,” she said.

“We wanted to take a risk and say, ‘This is what we stand for — putting artists in the midst of these urgent conversations.’”

The exhibit, which is kicking off with a celebration and panel discussion on Friday, will include never-before-seen sculpture, film, paintings and drawings from the artists, whose work combines history, research and storytelling. They are: Carolina Aranibar-Fernández, Juan Brenner, Raven Chacon, Sandra de la Loza, Ashley Hunt, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Michael Rohd, Paul Rucker, Xaviera Simmons, Stephanie Syjuco, Vincent Valdez and Mario Ybarra Jr.

Aranibar-Fernández is the current Race, Arts and Democracy Fellow in the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at ASU. Her mixed-media installation is called “Multi-ples Capos (Multiple Layers)” and includes sculpture, sound and organic plants.

“I was thinking a lot about displacement of land through incarceration but also what happens to the multiple layers and histories of the land that we see and what we don’t see,” she said.

Her installation includes a small wall out of adobe bricks made in Arizona, with some covered in gold leaf.

“Gold is an extracted resource but also a form of power,” she said.

Aranibar-Fernández hand-made dozens of tiles from clay and soil that are placed on the floor in front of the bricks. On each tile is etched the name of a company that profits from the carceral system such as through prison labor or surveillance systems. Museum-goers will walk on top of the tiles, which, as they break and grind down, will create dust that will settle into the plants.

“I’m thinking about what can grow again after things get destroyed and the cycles of destruction,” she said.

“For something to be constructed, something gets destroyed.”

Suspended above the tiles are several planters with medicinal plants such as sage and tobacco.

“The plants are medicinal for organs that have been damaged by oppression, such as the liver and lungs,” she said.

The installation also includes bright lights to mimic the use of light in prisons as a form of manipulation.

While Aranibar-Fernández’s previous work hasn’t dealt directly with mass incarceration in the U.S., her themes are related.

“All of my work has a conversation about extractive resources, exploitative labor, the histories of slavery and contemporary slavery, which incarceration is borne from,” she explained.

“Undoing Time” is an important way to have conversations about incarceration, she said.

“Art allows for that. We don’t have to speak the same language or know the same things,” said Aranibar-Fernández, who was a Projecting All Voices Fellow in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts in 2018.

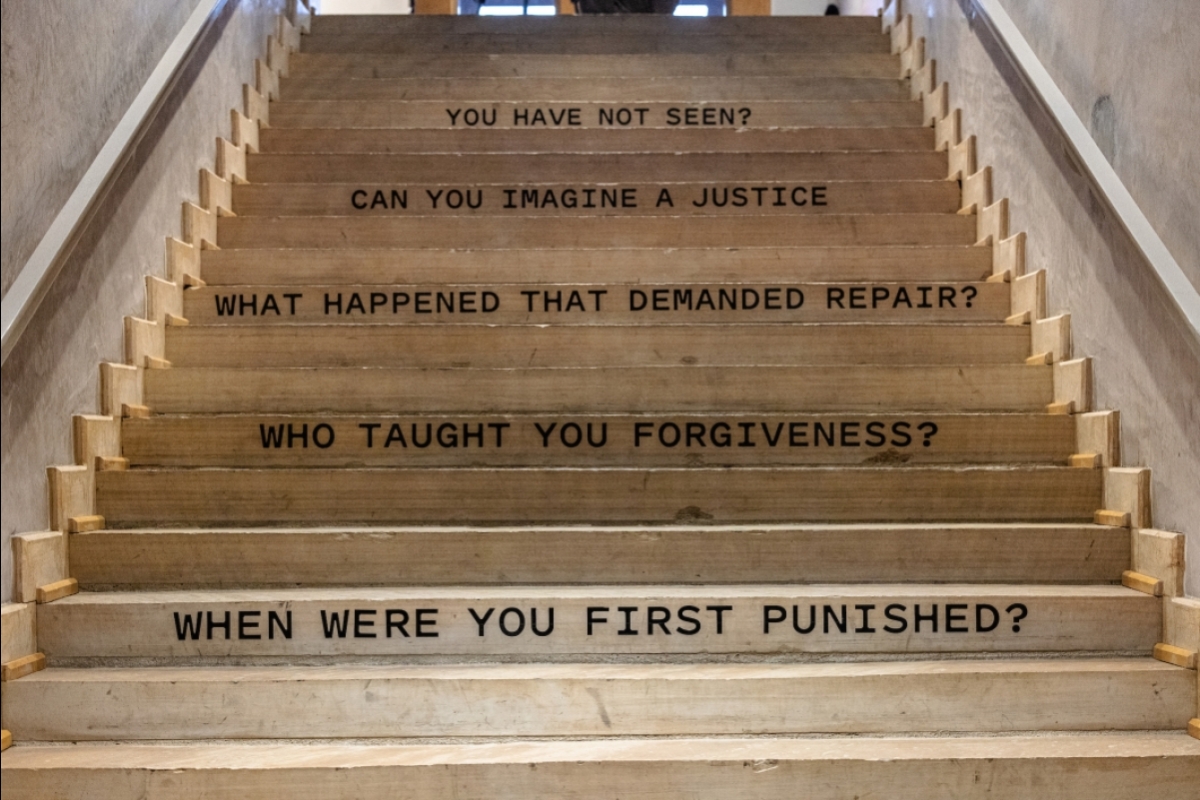

The “Undoing Time” curators want viewers to experience the exhibit in a different way, so they hired Rohd, an Institute Professor in the School of Music, Dance and Theatre, to choreograph the experience of walking through the museum. There will be one way in and one way out.

“He leads the viewer on a journey with a lot of questions, which are meant to be self-reflective, like, ‘What would a world look like where we loved instead of punished?’” Garcia said.

At the end of the exhibit is space for reflection and recuperation, and viewers can discover ways to become involved in the issue.

The spirit of this exhibit is to bear witness but also to imagine other possibilities for our world.”

— Miki Garcia, director of the ASU Art Museum

Unlike most exhibits, which are curated by a single person, “Undoing Time” has a team of curators: Garcia, Heather Sealy Lineberry, curator emeritus; Matthew Villar Miranda, ASU-LACMA Fellow, and Julio César Morales, senior curator.

“I quickly realized that that this multigenerational, multi-perspective curating was the right way to go,” Garcia said.

“We knew with this subject that there should be many participants because it is so interdisciplinary.”

The curators spent months researching the issue of incarceration by visiting correctional facilities and meeting with scholars, activists and communities affected by incarceration.

Miranda said that to research the art history side, the team scoured the internet for depictions of incarceration in artwork.

“We did a dragnet of phrases and words, such as sin, punishment, prisoner and criminal,” he said. They created a database of about 1,700 artworks that are categorized.

“For example, images of architecture are very prominent starting in the late 1700s to early 1800s, which coincides with the time that prisons became industrialized in western Europe.”

Researching those historical works was painful, Garcia said.

“We noticed that the history of these images perpetuates the way we think about prisons and why we might collectively decide that putting people in cages is the only way to deal with transgression,” she said.

“What we see over and over again, even by people who are well-meaning and activists, is the Black and brown body in chains, kneeling, on the lower side of the composition. Why do we never see Black and brown bodies thriving, or the mothers and children and communities of these Black and brown bodies?

“Why do we see the person chained, but not the system? The CEO of CoreCivic, the major prison builder in the U.S., is never represented.”

The curators didn’t want “Undoing Time” to create more pain.

“We wanted to be careful around why we would choose to represent images of incarceration when there are already so many,” she said.

Besides the historical research, the curators also invited the artists to meet with scholars to discuss incarceration and systemic racism.

“It was an important reflection on reform versus abolition, and the lack of imagination for new possibilities.”

The museum has scheduled several events for community members to explore themes of the exhibit and learn more.

“My plea is that it’s not an exhibit that is an echo chamber, but is really something that students and the community can use as a platform to discuss what is happening in our state today,” she said.

“The spirit of this exhibit is to bear witness but also to imagine other possibilities for our world.”

An installation by Stephanie Syjuco called "Shutter/Release" will be on display as part of the "Undoing Time" exhibit at the ASU Art Museum. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

Exhibit programming

All programming is free and open to the public. RSVP for each program you are interested in attending.

Opening Celebration

10–11 a.m. Sept. 10

ASU Art Museum

Join ASU Art Museum leadership, curators and exhibiting artists for the unveiling of “Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration.” Meet and hear from those involved and get a behind-the-scenes tour of the exhibition to hear unique perspectives from the artists and curators. Sponsored by La Bohemia.

“Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration”: Artist Panel

6 p.m. Sept. 10

Mirabella

Virtual link

A lively conversation with the artists and curators, this will be an opportunity to learn more about the artistic process, various themes and pertinent questions raised by this urgent exhibition.

Abolition 101

6 p.m. Sept. 21

Virtual link

A public conversation with Arizona-based grassroots organization Mass Liberation AZ, this workshop and discussion addresses the future of abolition, dream and practice. This event is free and open to the public and centers on student engagement and interaction. This program is organized in collaboration with the ASU Art Museum, Performance in the Borderlands, Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and Social Transformation Lab.

Journalists Reporting on Justice: Who Pays the Price for Righting Wrongs?

3 p.m. Sept. 22

Bateman Physical Science Building F-Wing Room 173

Speaker: Laura Gómez, reporter, AZ Mirror. This “Seeking Justice in Arizona” program is organized by the ASU School of Social Transformation’s Fall Lecture Series.

“Undoing Time” Roundtable: The Curatorial Perspective

6 p.m. Sept. 30

ASU Art Museum

Virtual link

Join us for a guided tour of the exhibition by the curatorial team who organized this project. Afterward, participate in a roundtable discussion on the research and processes that brought this exhibition together and learn more about the artists and about the artwork on view. Featuring: Miki Garcia, ASU Art Museum director; Julio Cesar Morales, senior curator; Heather Sealy Lineberry, curator emeritus; and Matthew Villar Miranda, ASU/LACMA fellow.

Building a Justice System Where No One is Left Behind

3 p.m. Oct. 13

Bateman Physical Science Building F-Wing Room 173

Speaker: January Contreras, founder, Arizona Legal Women and Youth Services (ALWAYS). This “Seeking Justice in Arizona” program is organized by the ASU School of Social Transformation’s Fall Lecture Series.

Arts and Liberation

6 p.m. Oct. 19

ASU Art Museum

Virtual link

Participate in a public conversation about the unique contribution of artistic and cultural practice toward a vision for social change. Hear from grassroots organizers for Mass Liberation; artists Sandra de la Loza, Carolina Aranibar-Fernández and Xaviera Simmons; and faculty who explore the ways symbolic and creative interventions can shape imaginations for what is possible. This program is organized in collaboration with the ASU Art Museum, Performance in the Borderlands, the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and Social Transformation Lab.

“Undoing Time” Roundtable — Mass Incarceration and Immigrant Policing in Arizona: Voices of Resistance

6 p.m. Oct. 28

ASU Art Museum

Virtual link

Leah Sarat, associate professor of religious studies in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, and local activist organizations will lead a discussion about the struggle for immigrant rights in Arizona and the ties between incarceration, immigrant detention and police violence in the state, with attention to cross-movement organizing and strategies for community healing. She will be joined by representatives from local activist organizations, including Puente and others.

We Occupy/We Dis-cover

1–4 p.m. Nov. 13

ASU Art Museum

In response to and part of the exhibition, a group of community justice scholars, artists and ASU graduate students will take over the museum to unseat, dis-locate and de-center notions of safety, imprisonment and control. Visit us and participate in a day of interventions, conversations and performances. After engaging in this transformative community work focused on mass incarceration, participants will leave with full hearts and minds. Organizers of this event are enrolled in ASU School of Art’s Art and Justice course (ARA 591), taught by Gregory Sale, associate professor in the School of Art, and Julio César Morales, senior curator at ASU Art Museum.

“Undoing Time” Roundtable

6 p.m. Jan. 20, 2022

ASU Art Museum

Virtual link

Speakers: Natalie Diaz, associate professor and the Maxine and Jonathan Marshall Chair in Modern and Contemporary Poetry. More information to come.

“Undoing Time” Roundtable: Critical Witnessing

6 p.m. Feb. 3, 2022

ASU Art Museum

Virtual link

Join Vice Provost and Professor Tiffany Lopez in a roundtable discussion about “critical witnessing.” This is a term Lopez coined to describe the process of stepping into a space of personal and/or social transformation as the direct result of experiencing a work of art that clarifies that one is part of the continuum of the work. Critical witnessing is the experience of seeing a work of art and realizing you do not want to directly participate in or indirectly perpetuate the history of violence and trauma in an artwork. The experience of the work brings a shift from passive viewer to active witness with critical awareness, emerging toward a path of change.

Dreaming Beyond the Carceral State

6 p.m. Feb. 8, 2022

Virtual link

What would it look like to live in a world without prisons? Join artists Ashley Hunt and Juan Brenner, with organizers from Mass Liberation, for a public conversation considering possibilities for justice and fairness that do not include a prison system. This program is organized in collaboration with the ASU Art Museum, Performance in the Borderlands, the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and Social Transformation Lab.

Also on view: “Journeys Toward Healing,” Sept. 10–Feb. 13, 2022, in the Art in Focus Gallery, ASU Art Musuem.

In the community: "Women of Perryville Prison Art Exhibit," 10 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Monday–Friday, Sept. 1–30, Olney Gallery at Trinity Cathedral, Phoenix.

Top photo: Carolina Aranibar-Fernández stands amidst her mixed-media installation, which is called “Multi-ples Capos (Multiple Layers)” and includes sculpture, sound and organic plants. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

More Arts, humanities and education

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…

Upcoming exhibition brings experimental art and more to the West Valley campus

Ask Tra Bouscaren how he got into art and his answer is simple.“Art saved my life when I was 19,” he says. “I was in a dark place and art showed me the way out.”Bouscaren is an …