In “Pride,” a new FX docuseries currently streaming on Hulu, ASU Associate Professor of film and media studies Julia Himberg describes the increased LGBTQ media representation of the 1990s and 2000s as an “explosion in queer visibility.”

Himberg is the author of “The New Gay for Pay: The Sexual Politics of American Television Production,” which examines the role of television production in creating and challenging popular notions about LGBTQ identities and social change.

She was featured in “2000s: Y2Gay,” the final episode of the six-part docuseries, which spans the struggle for LGBTQ civil rights from the 1950s through the 2000s.

“There've been several documentaries lately about LGBTQ history and media representation, which to me says that we've reached a kind of turning point, where there's enough interest that it's actually being documented as a history,” Himberg said.

“But I think the way that FX did their docuseries was kind of interesting and unique compared to the other ones I've seen because they tried really hard to tell the story of both the mainstream and the underground radical movements together, and to put those in conversation in ways that a lot of other documentaries have not, that is productive in opening people's horizons to a wider LGBTQ world.”

While the docuseries takes a broad look at LGBTQ history, ASU News sat down with Himberg to learn more about the significant role of media, and specifically television, in that history.

Julia Himberg

Question: One way to interpret the title of your 2018 book, “The New Gay for Pay: The Sexual Politics of American Television Production,” is that it alludes to the idea that popular shows featuring gay characters are actually exploiting gay identity for profit instead of sincerely celebrating it. What did you discover about that as you were writing the book and in the years since then? Is that actually what’s happening?

Answer: I think the word “new” in the title is really important because what I was trying to imply with that — with the definition of “new” and with the use of the term “the new gay for pay” — was that actually, television acts both progressively and exploitatively at the same time. There are cases in mainstream television, which we think of as this very normative space, where people are working sort of underground — I call it “under-the-radar activism,” because they often don't want to talk about it and they don't want the public to know about it — but they're doing work that is really activist-oriented toward LGBTQ people and communities, and at the same time, they are still able to meet the profit demands of the industry.

Q: Why does television specifically (or maybe nowadays, it’s more accurate to just say “episodic series,” depending on how you’re watching) as a medium have so much power to influence cultural/societal norms?

A: Television is so unique partially because it was established as a domestic medium, so it's more intimate than film. Television characters really become a regular part of our routines and lives, and I would say this is true even in the era of binge watching. And so television retains this uniqueness, I think even more now actually, because so much content now is available at home. Along with that, representation has come to matter tremendously for any social minority group. It's a form of what I would call cultural currency; when people see themselves represented in a medium as popular as television, it validates them and it tells them that they're a recognized and valued part of the national landscape. Representation is important for anyone, but I think it’s especially vital for LGBTQ youth who don't always have supportive families or school environments, so the first images we see of ourselves are often on television.

Q: The FX docuseries “Pride” spans the struggle for LGBTQ civil rights from the 1950s through the 2000s. You’re featured in the final episode, “Y2GAY,” which looks at the increased LGBTQ media representation of the 2000s and the “explosion in queer visibility” that precipitated it in the 1990s. What led to that initial explosion?

A: The '90s were definitely an important period. We certainly started seeing more gay characters in terms of quantity, but we also started seeing more quality representations of gay characters. But going as far back as the Stonewall riots in 1969, there was this turning point when people understood that television could play a key role in advancing the movement, whether through being involved in production, consulting on shows or even boycotting shows; there were all kinds of strategies used to be visible in television. And so you actually started to see more conversation about this and some gay characters in the 1970s. One of the more famous shows to do this was Norman Lear’s creation “All in the Family.” There were a whole bunch of episodes that talked about gay and lesbian characters — of course, back then, we still didn’t have the B, the T or the Q — in ways that were absolutely progressive. In the '80s, there was a bit of a conservative backlash, but there were still a lot of interesting made-for-television movies that were based on real stories. Sometimes it was a legal battle where a lesbian lost her children after she came out, or sometimes it was about people dealing with AIDS. And those were really important in changing hearts and minds.

Q: The final episode, “Y2GAY,” focuses more on the history of the fight for transgender rights, as well as the history of gay people of color. Why is it important to acknowledge those groups separately?

A: The simple answer is because they've so often been left out of the story. When you look at LGBTQ representational history, it's largely been a story of white, cisgender, mostly male characters. But LGBTQ experiences are not all the same; certainly they vary across racial lines, class lines, religious lines ... So dedicated attention to these histories is needed to correct the record and offer a more inclusive history.

Q: Is there such a thing as too much representation/overexposure? Can representation ever have a negative effect?

A: There's a term called “the burden of representation,” which means that whenever you have a first in terms of representation, there’s a lot of responsibility that comes with that. A decade or so ago, “The L Word” was that with lesbian representation — the first ensemble cast of all lesbian characters. Today, “Pose” is that for trans people. And so viewers can get to the point where they’re like, “Well, now I've done my homework. Now I know what all lesbians are like,” or “Now I know what all trans people are like.” And that can be problematic because it shuts down conversation when people think they know all there is to know. And shows have gotten a lot of critique for that. But it comes with the territory of being the first, because you simply cannot represent an entire community in one TV show. But they set the bar for the next round of shows to do even better, and that’s really important.

Q: Do you have any examples of any shows that are doing it right?

A: I do think “Pose” is a really important series in this conversation. And it's hard not to include something like “Schitt’s Creek,” which everybody loves to love. I think it does something pretty powerful by kind of creating a world in which homophobia doesn't exist. Another really interesting show that didn't get a lot of press but that really pushed the envelope much more around queerness was “Work in Progress.” “The Politician” is also interesting because it both reminds us how important identity categories still are and, at the same time, is kind of trying to be part of the generation that eschews those kind of labels. The documentary “Disclosure” gives a very good history of how trans people have been represented throughout film and media history.

Q: What’s your take on the state of LGBTQ representation in media today, and where do you see it going from here?

A: I think in general we can say that LGBTQ characters are certainly an expected and accepted part of the Hollywood landscape, especially on television. It’s past being a trend. And I would say we're seeing a push for more inclusive representation, both in front of and behind the camera. We're seeing this kind of closure on what has come before and a sort of incarnation of a new reality that includes a deeper, broader range of identities. There's also an increasing number of LGBTQ-dedicated media outlets, such as Revry and Open TV, that are focused on giving voice to LGBTQ media creators whose voices are typically not heard in Hollywood, especially creators of color. So the digital landscape has opened up opportunities for storytellers to tell their stories and to reach more audiences than ever before. So that’s a very important piece of what's happening, not just right now, but also as far as what the possibilities are for the future.

Top photo courtesy of Pixabay

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

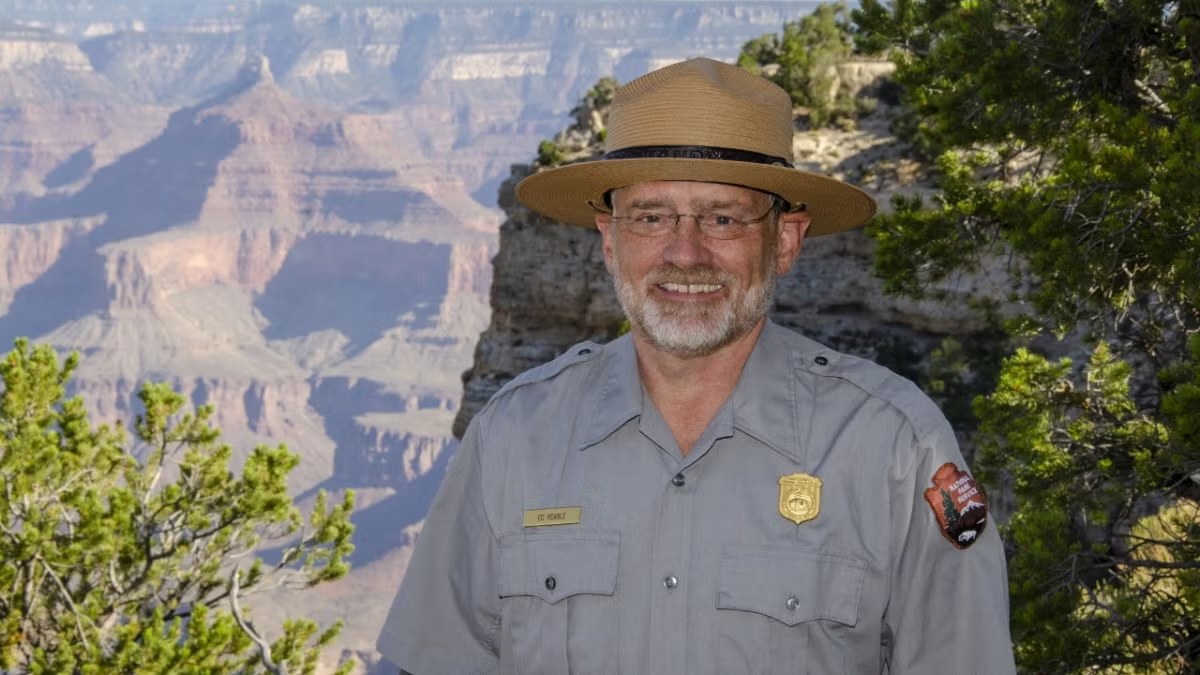

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…