Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the fall 2020 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

Serving amid the pandemic — as doctors, nurses and professionals — these Sun Devils have one thing in common: strong foundations in expertise, care and compassion, much of which they learned at ASU.

The nurse who goes above and beyond: Erolinda Becerra-Mendoza

For Erolinda Becerra-Mendoza, ’16 BS in nursing and health sciences, staying positive and tending to the emotional care of patients is as much a part of her nursing work as is physical care. “I’ve been working directly with COVID patients,” she said. “Half of the intensive care unit I work in is designated for them, although we are overflowing to our other unit.”

Erolinda Becerra-Mendoza

Although Becerra-Mendoza is a relatively new nurse with four years of experience, she says she’s never seen anything like the challenges that have arisen during the pandemic.

“I have seen a few success stories in the ICU unit I work in, but I have also seen patients not make it,” she said. “It breaks my heart knowing that they are not surrounded by family during their last hours of life. I love being a nurse, and I try to make this scary time as special as I can for my patients.”

A perfect example? Becerra-Mendoza had a patient who was about to celebrate a birthday. She took the initiative to ensure it was a happy one.

“A few nurses and I surprised him with a video conference with his family and grandchildren,” she said. “We got him a sugar-free cake and decorated his room. We had to make it special.” And they did.

The ER doc: Mara Windsor

As an emergency room physician and chief wellness officer, Dr. Mara Windsor, ’98 BS in psychology, faces COVID-19 on a daily basis. Throughout the pandemic, she’s focused on exceptional patient care, as well as ensuring that her colleagues emphasize their own self-care, particularly given the everyday stressors they face.

“I have seen some devastating situations, but I’ve also seen renewed spirit in humanity by people coming together to accept, understand and support each other,” Windsor said. “My nonprofit organization, L.I.F.E. (Living in Fulfilled Enlightenment), has been supporting the front-line heroes by providing personal protective equipment, food and emotional support.”

Most recently, the organization received a donation of 70 backpacks and 70 lunch sacks from the kids’ backpack company MadPax, all of which will be passed along to the children of health care workers as they make their way back to school.

“It is through our individual diversity that we can come together collectively to meet the needs of our community and society,” Windsor said. “This is the perfect time to create a global movement that will align human compassion with understanding and acceptance of all. I believe that this will result in greater love and compassion for all.”

The compassionate caregiver: Carmen Dominguez

Carmen Dominguez

As a certified medical assistant for Abrazo Medical Group, Carmen Dominguez, ’19 BS in health care coordination, works at a small clinic, helping to treat a variety of medical issues. While she acknowledges that COVID-19 has presented a lot of new challenges, she’s grateful that her patients can be seen quickly — and without the stress of having to go to the emergency room.

“Day in and day out, I hear patients telling me they are glad the clinic I’m working at is still open and accepting patients,” she said. “Working mainly with elderly patients, it is not an option to head to the emergency room when they feel heart-related symptoms. We are able to welcome them into a smaller setting than a hospital, (where they are able) to be seen and assessed — and possibly triaged — in-person. We are glad to be here to help and be of service.”

She adds: “I am so proud of my fellow Sun Devils, those working in hospitals, clinics, urgent cares, etc. Everything makes a difference! For those who have yet to graduate, please keep going! We need you.”

The mobile testing innovator: Farah Al Besher

For Farah Al Besher, ’14 BS in economics, who now works as a front-line coordinator with Ambulatory Healthcare Services-SEHA in the United Arab Emirates, early action meant early containment of the virus in her country.

“I am part of the COVID-19 National Screening Service Drive-Through project in the United Arab Emirates,” Al Besher said. “We were the first to open the drive-thru testing center in the UAE, and due to its success, we were asked to expand our presence by the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces. We were able to build 12 new drive-thru screening centers throughout the seven emirates in 10 days, and today we have 18 fully operational centers. By ensuring early detection of positive cases we have been able to increase the safety of our people.”

The United Arab Emirates experienced a spike in mid-May, followed by a steady decline in positive cases and a subsequent early July resurgence. Since, though, the country has seen a sustained reduction in COVID-19 cases.

“Life’s challenges are not supposed to paralyze us,” Al Besher said. “We are all equipped and ready to face any crisis. And remember, you can’t help others without first taking care of yourself. Follow the health guidelines, stay safe and remain positive.”

The mentoring engineer: Aaron Dolgin

Service and inspiration are just two of the things that motivate Aaron Dolgin, ’18 BS in electrical engineering. Now a systems engineer for Northrop Grumman in Los Angeles, much of Dolgin’s day-to-day life involves a fusion of his love of robotics and systems engineering, and providing for the community.

Aaron Dolgin

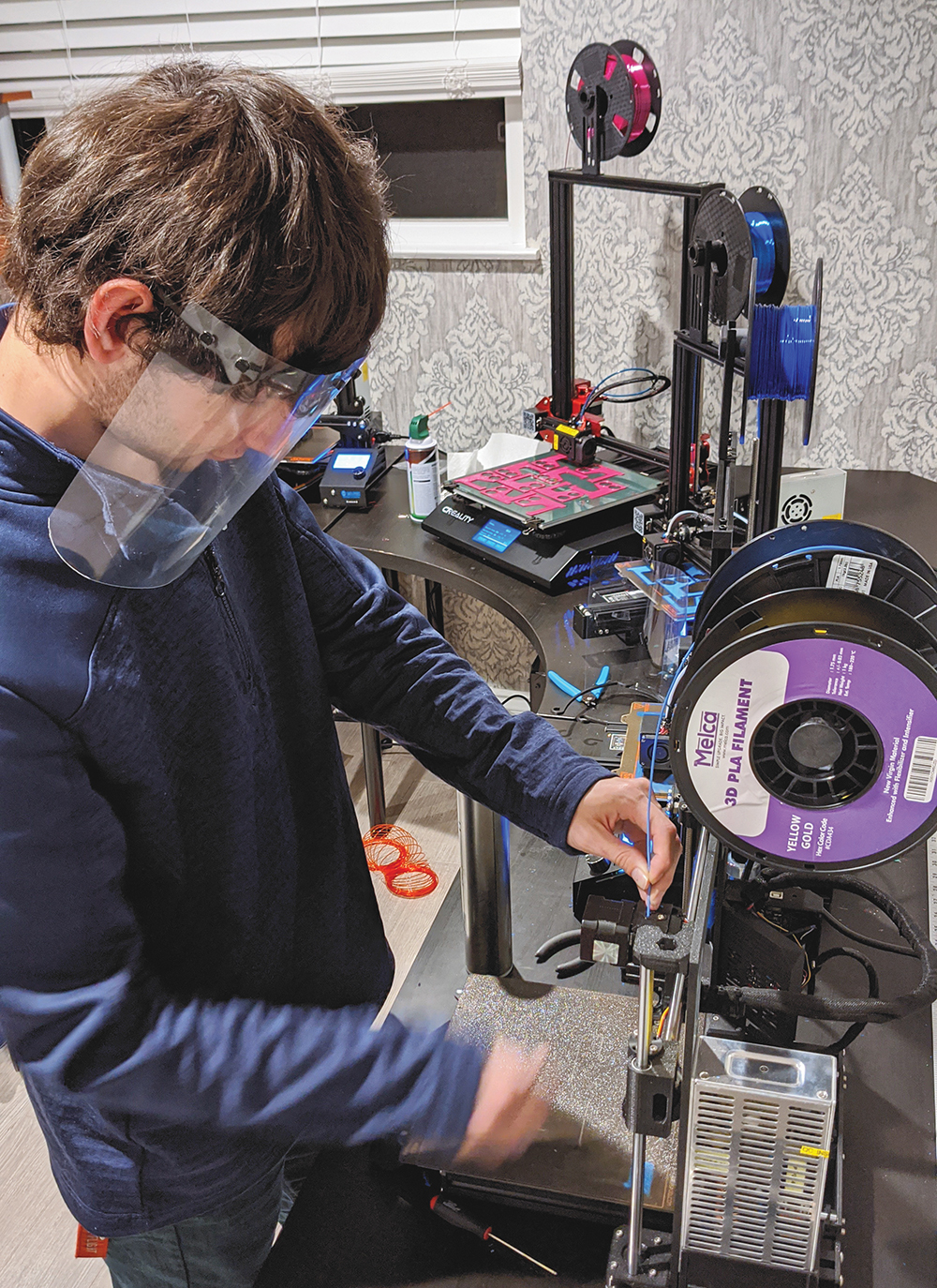

When the pandemic began, Dolgin co-founded a team of more than 150 people who are working to create, print and distribute face shields across Southern California. To date, SoCal Makers COVID-19 Response Team has manufactured and delivered more than 22,000 pieces of personal protective equipment.

Based on designs and specifications available through the National Institutes of Health, the face shields are 3D-printed visor frames with transparent sheets attached. And many of them are being produced by student volunteers — an extension of Dolgin’s mentorship while he was at ASU.

“I really enjoyed the robotics program in high school, so I wanted to make sure I gave back in some way,” Dolgin said in June. “During college at ASU, I volunteered at robotics events in Arizona, and I knew I wanted to continue that kind of support when I came back to California. Volunteers don’t need any prior technical knowledge. They may struggle a little at first, but we have a remarkable community ready to get everyone up to speed. All of us are figuring things out together.”

The emergency flight nurse: Christopher Banks

Indeed, compassion is a common theme among alumni health care workers, including Christopher Banks, ’18 BS in nursing, a flight nurse and paramedic for Air EMS Inc. Very early on during the pandemic — in late February — Banks was dispatched to assist in the transport of passengers who had been quarantined aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship off the coast of Yokohama, Japan.

“When I reached out my gloved hand, in full PPE, patients couldn’t believe they could touch and shake my hand,” Banks remembers. “This was heart-wrenching.”

Air EMS uses a special isolation unit to safely transport people suffering from COVID-19 that ensures that the paramedic crew and pilots aren’t exposed. It looks like a clear rectangular bubble for patients to lay in on top of the gurney. Banks helped test and train personnel on the isolation unit’s use as the pandemic worsened.

“As a base manager of our air medical transport company, I ensured that all of our care staff safely experienced the confined space of our isolation units to build better compassion for the patients.”

Looking to the future

While a vaccine for COVID-19 remains on the horizon and the world continues to adjust to life in a pandemic, there are a lot of uncertainties. But one thing does seem certain: Current students and researchers, as well as alumni, are working tirelessly — and compassionately — to ensure quality care for a global society.

To learn more about ASU’s Health Heroes or to submit your story, see alumni.asu.edu/healthheroes.

Written by Kelly Vaughn, the senior editor for Arizona Highways. Vaughn, ’04 BA in journalism, has written for many publications including Phoenix magazine and Arrive.

Top photo: (From left) Flight emergency nurse Christopher Banks, ambulatory health care services coordinator Farah Al Besher and emergency room doctor Mara Windsor. Photos by ASU

More Health and medicine

ASU researchers discover new digestive process for medication

“Detoxification” is a word most of us have heard, usually in the context of shakes or supplements. But what does it actually mean? In our bodies, it is the natural, or medicinally assisted, removal…

ASU students produce winning video showing dangers of fentanyl use

The message appears one second into the 26-second video: “Fentanyl is 50x stronger than heroin.”The wording is in white, except for “50x” which is bright red.Then, immediately, another message: “…

ASU expands health care services to employees

You’re an Arizona State University employee, you’re nursing some sort of infection that just won’t go away, but your doctor’s office doesn’t have an available appointment for at least a week.What do…