As an MBA student, Abby Rudd never imagined that evaluating sanitation truck design would be a valuable part of her education. But like the other 36 graduate students at Arizona State University who participated in a project to design a “Garbage Truck of the Future,” she gained insights about real-world problems that she believes will give her a head start in her career.

The 36 graduate students — 18 studying business at the W. P. Carey School of Business and 18 studying industrial design at the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts — worked from August to December last fall incubating ideas that could transform Republic Services’ garbage collection trucks into models of 21st-century safety and efficiency.

Each team included a mix of design and business students, who worked together to ensure that designs met engineering requirements and were economically feasible. At the end of the project, teams presented their ideas to Republic Services, one of the nation’s largest recycling and waste disposal companies.

“It was a terrific program, and the students gave us some interesting results,” said Brett Beitzel, Republic’s director of fleet and asset management. The company plans to evaluate the ideas and include them as part of its strategic technology road map.

A fresh set of eyes

Republic Services, which is headquartered in Phoenix and regularly recruits at ASU, approached the university after learning it had a cross-functional program bringing together teams from different schools to work on real-world projects.

The program is designed to give students the experience of working with other disciplines, said Kevin Dooley, a professor of supply chain management at the W. P. Carey School of Business.

Projects always have a corporate or government sponsor, adding a valuable real-world dimension. In 2018, students partnered with the city of Mesa to collect food waste from restaurants, hotels and grocery stores, and turn it into compost and fuel. The city is currently evaluating the plan.

In 2019, Republic wanted a fresh set of eyes to improve its truck design, which is standard across the industry.

“We were looking for a partner to help us improve efficiency and make the job less strenuous for drivers,” Beitzel explained, adding that the company consults with equipment vendors who supply its trucks. “But we wanted to think differently than we normally do. We’re so close to the subject that we get locked in our linear path.”

To understand the problems Republic wanted to solve and generate solutions, the students spent weeks poring over customer and driver survey data that the company had shared, as well as conducting internet research. They also followed garbage truck drivers around to observe their motions and talked to former drivers about pain points on the job.

The ideas that emerged were anything but linear, with many incorporating the kind of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technology used by autonomous vehicles.

“The theme was making trucks smarter so that drivers don’t have to do as much,” Dooley said. Reducing the possibility of human error improves safety, and easing demands on drivers reduces stress and makes training faster.

A garbage unit that drives itself to the dump

One of the more far-out ideas was a garbage-carrying truck body that disconnects from the cab and drives itself to the dump. Industrial design student Patrick Andrus was on the team that came up with that concept.

In current operations, drivers can’t get through a route without making periodic side trips to a transfer station — a sort of way station between the truck route and the more distant dump — to drop off their loads. Other trucks later transport waste from the transfer station to the dump.

Because garbage trucks are so heavy, they cause more wear and tear on roads than other vehicles, and cities often require them to drop off their loads when they’re just 75% to 90% full. “But they’re only making money when they’re collecting garbage,” Andrus pointed out.

Under the system his team developed, whenever a truck reaches its load limit, its garbage unit would detach from the cab where the driver sits and, using autonomous-vehicle technology, drive itself to the dump.

Garbage units would communicate with one another so that as one is ready to head to the dump, another returning from it would hook up with the cab of the first truck, enabling drivers to seamlessly continue along their routes as trash is hauled away.

With truck bodies driving directly to the dump, there would no longer be a need to operate complex transfer stations. Some could be used as parking lots for returning truck bodies, while others could be turned into parks or other municipal sites.

Reducing the operating costs of transfer stations would save Republic somewhere around $70 million a year, the team estimates. The system would also make drivers more efficient. “All drivers would be collecting garbage at all times,” Andrus said.

Also, Andrus’ team suggested making trucks out of a light, carbon-fiber-and-aluminum material, estimating that it would save the company an additional $78 million a year by lowering fuel costs.

Sensors that make trash pick-up easier and safer

Abby Rudd’s team’s idea involves using precision sensors for picking up trash from bins, which isn’t as easy as it sounds. Like Andrus’ team, Rudd’s group focused on front-loading commercial-waste trucks, Republic’s most profitable line of business. The trash bins they empty are often located in confined spaces or surrounded by a gate. Truck drivers must angle their big trucks back and forth until its hydraulic arms are in just the right position to reach a bin.

In addition to being time-consuming, this process introduces risk.

“Lots of accidents occur when you’re backing up,” Beitzel said. “Our drivers use cameras and sensors, but it’s still the hardest place to see. If you can reduce backing, it will improve safety a ton.”

Rudd’s team created an AI sensor system that would guide a truck to the perfect location for retrieving a bin on the first try, increasing driver efficiency and eliminating dangerous back-and-forth maneuvering.

The system could save Republic over $130,000 a year on labor and fuel for each route, Rudd said. With the time it saves on trash pick-up, the company might be able to add new customers to a route, increasing the benefit to $170,000 a year per route. If Republic implemented the system across its nationwide fleet of over 4,000 trucks, it could serve more than 14 million additional bins without taking on new drivers or ordering new trucks, the team found.

A host of innovations

Not all ideas centered on AI. Teams looked at the equipment used at mines, ports and other facilities to come up with ideas that could make trash hauling easier, faster and safer.

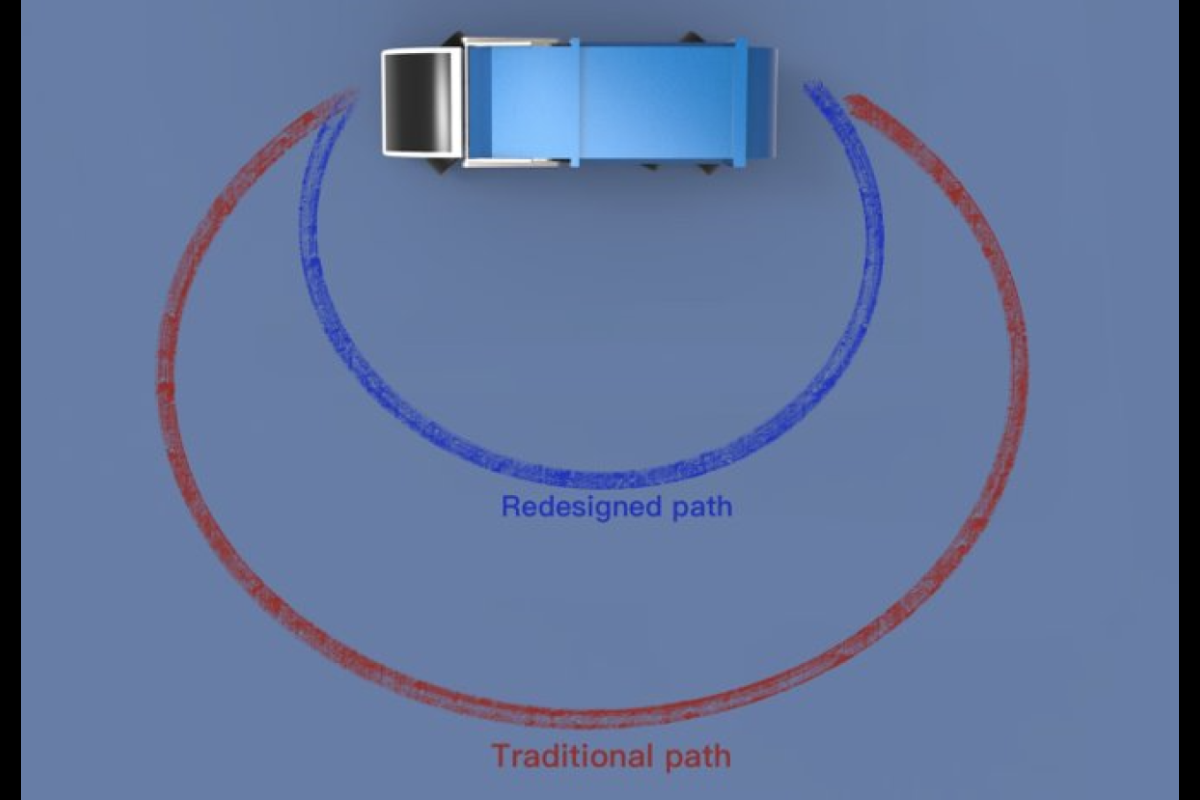

One team devised a rotational axle system that would enable big trucks to turn 360 degrees on a dime. Another designed a truck with arms that could be rotated front-to-side so that the same vehicle could be used for overhead pick-up of commercial waste and side pick-up in residential areas. Yet another team created a “perpetual motion” system, in which a truck would slow down, but not quite stop as trash is picked up along the route.

Republic Services appreciates the cross-pollination of ideas. “A lot of people took ideas from other industries. There was an interesting mix of thinkers,” Beitzel said.

A different kind of learning

By brainstorming with people from other disciplines, students gained a new perspective.

“It was exciting working with MBAs. As designers, we usually work on our projects individually,” Andrus said.

“I had never worked with people with a design mindset,” Rudd said. “The way they approach problems is so different.”

Observing a real company’s operations and explaining findings that might someday be applied also opened a new window for the students.

“You’re presenting to people who have knowledge in the industry and are invested in the outcome of your ideas,” Andrus said.

“No matter what you’re doing, defining and analyzing a problem, getting to the root cause, brainstorming and discussing the business case is going to be relevant. It’s a process I know I can leverage for a future role,” Rudd said.

More Arts, humanities and education

Professor's acoustic research repurposed into relaxing listening sessions for all

Garth Paine, an expert in acoustic ecology, has spent years traveling the world to collect specialized audio recordings.He’s been…

Filmmaker Spike Lee’s storytelling skills captivate audience at ASU event

Legendary filmmaker Spike Lee was this year’s distinguished speaker for the Delivering Democracy 2025 dialogue — a free…

Grammy-winning producer Timbaland to headline ASU music industry conference

The Arizona State University Popular Music program’s Music Industry Career Conference is set to provide students with exposure to…