ASU professor testifies before US Senate about long-term impacts of cannabis use

ASU Assistant Professor Madeline Meier is shown in a screenshot speaking before the U.S. Senate International Narcotics Control Caucus on Oct. 23.

What do a pen and the string of a hooded sweatshirt have in common?

Both can discreetly deliver cannabis products such as marijuana, and both are popular with teenagers.

Marijuana impairs cognitive function at least temporarily, and in certain circumstances the cognitive effects can persist long-term.

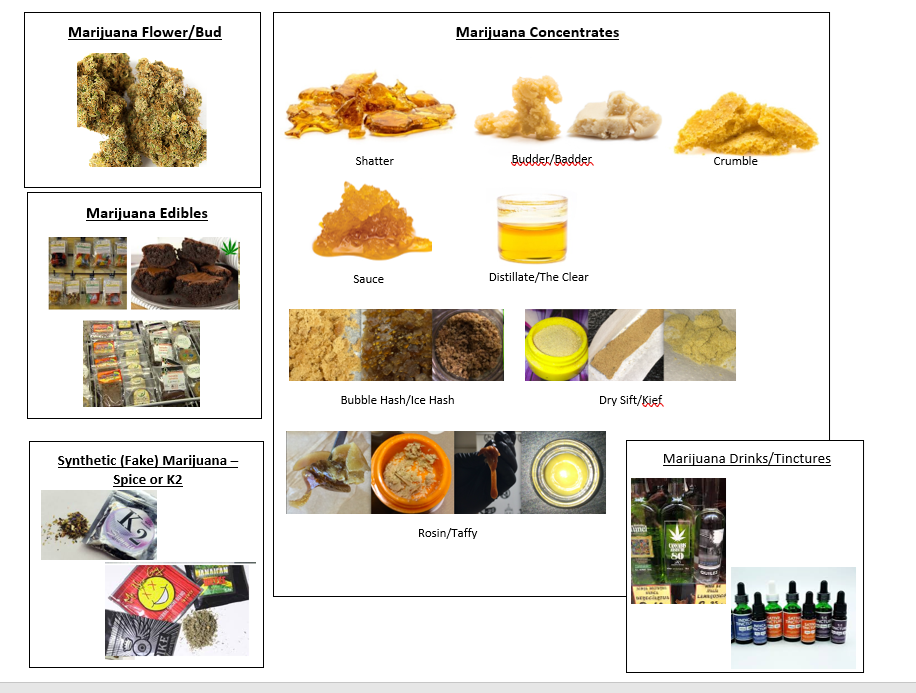

Over the past 20 years as cannabis products — like marijuana from the buds of the plant and concentrates from cannabis plant materials — have become legal for medical and recreational use, the potency has dramatically increased. The potency of a cannabis product is based on how much tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, it contains. People today can be consuming cannabis products that are much stronger than the joints smoked by previous generations.

The U.S. Senate International Narcotics Control Caucus recently held a hearing on cannabis use, and Arizona State University’s Madeline Meier testified about the vulnerability of adolescents to cannabis effects on cognitive functioning. She also discussed the rise of concentrate use in Arizona youth.

“The senators wanted to understand whether there is an increased risk of addiction, cognitive impairment and even psychosis given the increase in THC potency over the past 20 years,” said Meier, who is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology. “It is not yet clear how the potency of cannabis affects the risk of becoming addicted or how it affects long-term health.”

Cannabis that doesn’t look or smell like marijuana

In 2012, Meier and her collaborators published a study on the long-term effects of cannabis use using data from the Dunedin Study, which started in 1972 and has followed more than 1,000 people since birth. Heavy and frequent cannabis use that began during the teenage years and continued for many years afterward was associated with an eight-point reduction in IQ. Short-term cannabis use in adolescence was not associated with IQ decline, and people who started using cannabis after age 18 did not show a decline in IQ, even with long-term heavy use.

“Our findings suggest that adolescents might be particularly vulnerable to the effects of persistent cannabis use on IQ decline,” Meier said.

The potency of the cannabis used by the Dunedin Study participants was 3.5% THC. The potency of cannabis products available today can be in the range of 40-70% THC, and sometimes as high as 80% THC.

Cannabis products.

Meier and her colleagues at ASU recently found that nearly 1 in 4 Arizona teenagers report using cannabis plant extracts with ultra-high THC content, called concentrates. Made by extracting THC from the cannabis plant, these products can be a liquid or a solid substance with an uncanny resemblance to earwax.

“Kids can be using cannabis, but it doesn’t smell or look like marijuana,” Meier said.

Despite the high prevalence of concentrates, there is almost no research on how THC content modulates the severity and duration of cognitive impairment from cannabis or whether it contributes to the risk of becoming addicted.

Studying the long-term effects of cannabis use is difficult. Ideally, scientists want to assess participants before any have used cannabis and then several times afterward. This type of experiment requires following people for decades, and there are not many datasets like the Dunedin Study that allow scientists to examine the effects of cannabis use across the lifespan.

The Dunedin study participants are now 45, and Meier and her collaborators are assessing how cannabis use impacts aging-related cognitive declines.

Meier told the Caucus that there is an ongoing need for long-term studies of the impact of cannabis use on youth. In 2015, the National Institutes of Health funded the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study (ABCD Study), in part to answer questions like how experiences like substance use affects how children develop. The ABCD Study is currently following 10,000 American children starting at age 9-10 years. It will be several years before data about cannabis use, including the use of concentrates, is available. In the meantime, Meier is working on understanding the impacts of cannabis use using data she collects from adolescent and young-adult cannabis users.

More Law, journalism and politics

A new twist on fantasy sports brought on by ASU ties

A new fantasy sports gaming app is taking traditional fantasy sports and mixing them with a strategic, territory-based twist.…

'Politics Beyond the Aisle' series to explore the stories of public officials

In an effort to build a stronger connection between students and political and civic leaders, Arizona State University’s School…

ASU committed to advancing free speech

A core pillar of democracy and our concept as a nation has always been freedom — that includes freedom of speech. But what does…