School of Human Evolution and Social Change alumna Sara Becker has one particularly clear memory from her undergraduate years at Arizona State University: the time she nearly ran over Donald Johanson — founding director of the Institute of Human Origins and renowned discoverer of the Lucy fossil — with her bicycle.

“He stepped out in front of me as I was biking past the Social Sciences building, and I thought, ‘Oh no, if I hit Don Johanson, I’ll never get to be an anthropologist!’” she said. “Luckily, we both have fast reflexes, and no one was injured.”

Becker rides in a teleferico, a gondola lift, above La Paz, Bolivia. Photo courtesy of Sara Becker

Despite her fears, Becker did go on to become a successful anthropologist in her own right. Today, she studies the Tiwanaku civilization, which thrived in the Andes region from A.D. 500–1100. As a bioarchaeologist, she looks for the traces that everyday activities left on human skeletal remains. For societies like the Tiwanaku that didn’t have writing systems, the body can speak volumes about how ancient people lived.

To better understand the physical movements that accompany traditional labor, and thus the signs those repeated movements would leave on a skeleton, she has turned to an unexpected tool — motion capture technology.

The technique first grabbed her attention as an undergraduate student, when movies and video games began using it more widely. So later, when she started looking for ways to gather data on movement, it readily came to mind.

“It seemed like a natural fit,” Becker said, especially because it has become more common and less expensive since it was first introduced.

While Becker can’t record the motions of Tiwanaku people who lived long ago, she can record their descendants, the indigenous Aymara people who live in Bolivia and Peru. Many still do traditional labor that may be similar to that of their ancestors.

To capture motion in the field, she and her research assistant interview subjects about the types of activities they perform and then invite them to the motion capture lab. If they agree, the researchers pay for the subjects’ time and materials and have them demonstrate their tasks.

“We ask the person to wear little motion capture dots, which kind of look like tiny ping pong balls,” Becker said.

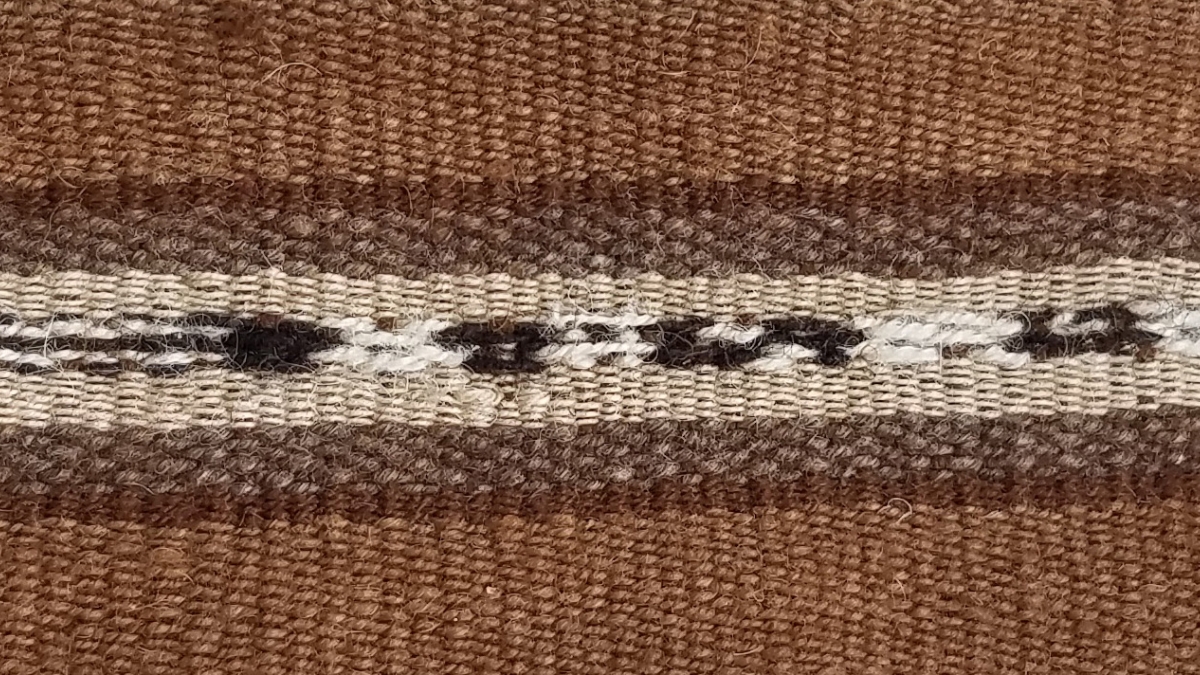

An Aymara woman wearing motion capture dots weaves a narrow textile out of alpaca wool, using the bottom legs of a kitchen stool. Photo courtesy of Sara Becker.

Ten cameras arranged in a circle around each subject record the person and dots from 360 degrees. Later, Becker uses a special software to create models of the subjects’ movements.

Though she is in the early stages of her research, she is already learning more about how specific tools must be used and the ways in which a person must move — or even stay still — in these types of labor, which aids her understanding of the skeletal evidence.

She hopes the new motion capture data will help draw clearer connections between some of the labor of Aymara people and that of their Tiwanaku ancestors, as well as create a more robust visual and verbal record of experts working at their crafts, such as weaving or ceramics, for future generations.

Her biggest takeaway so far is that this ancient society had a surprisingly egalitarian approach to labor — a finding which may hold clues to how members of our own complex society can better collaborate on large projects.

“My research has shown that people organized labor in ways we don’t normally associate with traditional, state-level societies,” Becker said. “Tiwanaku people likely labored reciprocally, sharing the major agricultural work, and were not conscripted or enslaved into labor.”

Becker credits her undergraduate courses at ASU — such as Human Osteology and Death and Dying in a Cross-cultural Perspective — and faculty mentors such as Associate Professor Brenda Baker, with creating a solid foundation for the rest of her scholarly career.

“All of these classes have translated into entry-level expertise that I built upon and gave me ideas to pursue in my own research,” she said. “I also met a great number of people, both friends and professors, who guided me and gave good advice.”

Her own words of wisdom for current students echo that same guidance.

“I suggest practical experience, getting to know some of your professors and trying things hands-on to see what you’re good at,” she said.

And maybe, if you can manage it, avoid running over famous scientists.

Top photo: The Aymara weaver's finished textile product features a traditional pattern. Photo courtesy of Sara Becker

More Science and technology

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…