When it comes to climate change and carbon reduction, Susanne Neuer is thinking small — extremely small.

The Arizona State University biological oceanographer is an expert on marine phytoplankton, microscopic algae found in the sunlit zone of waters all over the globe. As Neuer is quick to point out, phytoplankton may be small — too small individually to be seen with the naked eye — but they are mighty. Their size belies their critical importance to the biological carbon pump, the primary biological mechanism in the ocean’s absorption of vast quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

“The oceans take up a quarter to a third of all CO2 emissions,” she said. “Phytoplankton are one of the key players for how that works.”

As CO2 emissions have soared, the ocean’s role as a carbon lockbox has become ever more critical. Neuer’s research examines how different types of phytoplankton prime the ocean’s biological carbon pump — and how climate change might affect their ability to keep the pump running.

“The chemistry of the ocean is changing,” she said. “We don’t know yet what the consequences will be.”

Exploring the ‘world within a drop’

NeuerNeuer is also a professor in the School of Life Sciences and a senior sustainability scientist in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability at ASU. has always been drawn to the “world within a drop.” During her childhood in Germany, she spent summers in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, exploring life below the surface. At 13, she saved up to buy her first microscope so she could examine water samples she drew from local ponds.

“The microscope opens up this whole other world that you can’t see otherwise,” she said.

Her academic career took her between Europe and the U.S., with early fieldwork in the Canary Islands. She came to ASU in 2004 and became tenured faculty in 2008, bringing an expertise that might seem out of place in the dry desert of Maricopa County, 350 miles from the nearest ocean.

But she notes that the delicate balance of life in the desert parallels increasing “ocean deserts” from the perspective of climate change. And distance hasn’t deterred her from continuing work on a subject that captivated her: the biological carbon pump.

The biological carbon pump starts with a process that all schoolchildren learn about in science class: photosynthesis. Marine phytoplankton use sunlight to absorb carbon dioxide that has dissolved into the water and convert it into carbon in their bodies.

“A fraction of those phytoplankton is grazed by larger zooplankton, and their carbon is incorporated into fecal pellets that sink,” Neuer explained. “Phytoplankton don’t need to die to aggregate; their cells are tiny, no matter if alive or not, so they float. Those that aggregate into larger particles, called marine snow, become heavy enough to sink to the depths of the ocean. The carbon in those particles and pellets is removed from contact with the atmosphere for tens to many hundreds of years.”

The pump is by no means a closed system. Bacteria, nutrient levels, even dust borne on the wind from the Sahara Desert and dropped in the ocean all exert an influence. To identify the elements and types of phytoplankton at work in the pump, Neuer plies the waters of the Sargasso Sea, a region of the North Atlantic off Bermuda.

Susanne Neuer's research team works in the Sargasso Sea, a vast patch of ocean named after a free-floating seaweed called Sargassum. It hosts hatching and feeding grounds for many fish, including eel and tuna, with microscopic phytoplankton at the basis of the food web. Photo by Doug Bell

Oceans in the lab

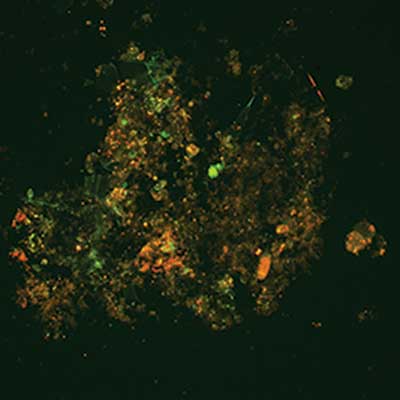

Neuer’s current research, funded by a National Science Foundation grant, focuses on the tiniest of phytoplankton, particularly picocyanobacteria, which thrive in the nutrient-poor Sargasso Sea. Previously, scientists considered them too small to play a role in the biological carbon pump. But Neuer’s DNA analysis of the particles collected in her traps found that picoplankton overcome not only their size but lack of nutrients by sinking into the deep ocean. Her research team also discovered that some species produce a slimy substance called transparent exopolymeric particles, which creates aggregates heavy enough to sink.

“As the air and oceans warm, the projection is that we’ll have more of these smallest of cells that can deal better with low-nutrient situations,” Neuer explained. “These little guys will become more important.”

Back in Neuer’s lab on ASU’s Tempe campus, second-year environmental life sciences PhD student Bianca Nahir Cruz puts picocyanobacteria through the paces in roller tanks. These “oceans in the lab” simulate the long drop through the water column to the ocean floor. Cruz is studying how picocyanobacteria make the aggregates that eventually sink as marine snow.

“We know that marine snow in its natural environment is a complete community, with a plethora of microbial interactions,” Cruz said. “We want to further study those interactions.”

Neuer’s NSF grant, “Aggregation of Marine Picoplankton,” is the first awarded to ASU’s new Biodesign Center for Fundamental and Applied Microbiomics (CFAM).

“Being a biological oceanographer here in the desert can be isolating,” she said. “So it is wonderful to have this community of scientists who all have microbes in mind.”

Tiny microbes, enormous importance

Among them is her partner on the NSF grant, Hinsby Cadillo-Quiroz. His team specializes in deciphering the roles of microbes in carbon cycling. Their fieldwork usually takes them to compact soil survey sites in the Amazon rainforest. He’s excited to work with Neuer on such a dramatically different site and scale.

The Neuer lab uses particle traps (pictured) to collect sinking aggregates in the Sargasso Sea. Picocyanobacteria and other small phytoplankton can be identified in the aggregates.

“Microbes have the power to change the world we live in,” he said. “The carbon pump can be driven by trillions of microbes working at very small scales, perhaps a few micromillimeters, but they have large-scale consequences.”

Neuer is collaborating with other colleagues beyond CFAM. She plans to include ASU undergraduates in her first joint experiments with the Bermuda Institute for Ocean Sciences to investigate larger planktonic animals in the Sargasso Sea and their role in helping phytoplankton aggregate.

“When most people think of the ocean, they think of large creatures, like whales, dolphins or turtles,” she said. “But in reality, the ocean is run by microbes. The enormous importance of these tiny organisms is unbelievable.”

Written by Kristin Baird Rattini, who has shined a spotlight on fascinating people and places for several national publications, including National Geographic Books, Discover, People, Fodor’s, American Way and U.S. News & World Report. This story originally appeared in the spring 2019 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

Top photo: Probing the world of microbes, Susanne Neuer (right) and PhD student Bianca Nahir Cruz observe different types of phytoplankton cultures in their ocean lab. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

More Science and technology

ASU in position to accelerate collaboration between space, semiconductor industries

More than 200 academic, business and government leaders in the space industry converged in Tempe March 19–20 for the third annual Arizona Space Summit, a statewide effort designed to elevate…

A spectacular celestial event: Nova explosion in Northern Crown constellation expected within 18 months

Within the next year to 18 months, stargazers around the world will witness a dazzling celestial event as a “new” star appears in the constellation Corona Borealis, also known as the Northern Crown.…

ASU researcher points to fingerprints as a new way to detect drug use

Collecting urine samples, blood or hair are currently the most common ways to detect drug use, but Arizona State University researcher Min Jang may have discovered something better.Fingerprints…