Growing up in Pennsylvania, Barbara McConnell Barrett dreamed about Arizona since her father traveled West during the Depression as a cowboy.

When she was ready for college, she had a plan — come to Arizona for a semester and then return East to finish her education. She requested catalogs from all three state universities and says “Arizona State’s was the prettiest.”

Today, ASU is also one of the nation’s best, partly because Barrett’s plan happily evaporated after coming to Tempe. “I never left,” she says, “and that was 50 years ago.”

She earned bachelor’s, master’s and law degrees at ASU, becoming the first woman to run for governor in Arizona and the first civilian woman to land an F/A-18 Hornet on an aircraft carrier during a distinguished career that included a stint as U.S. ambassador to Finland.

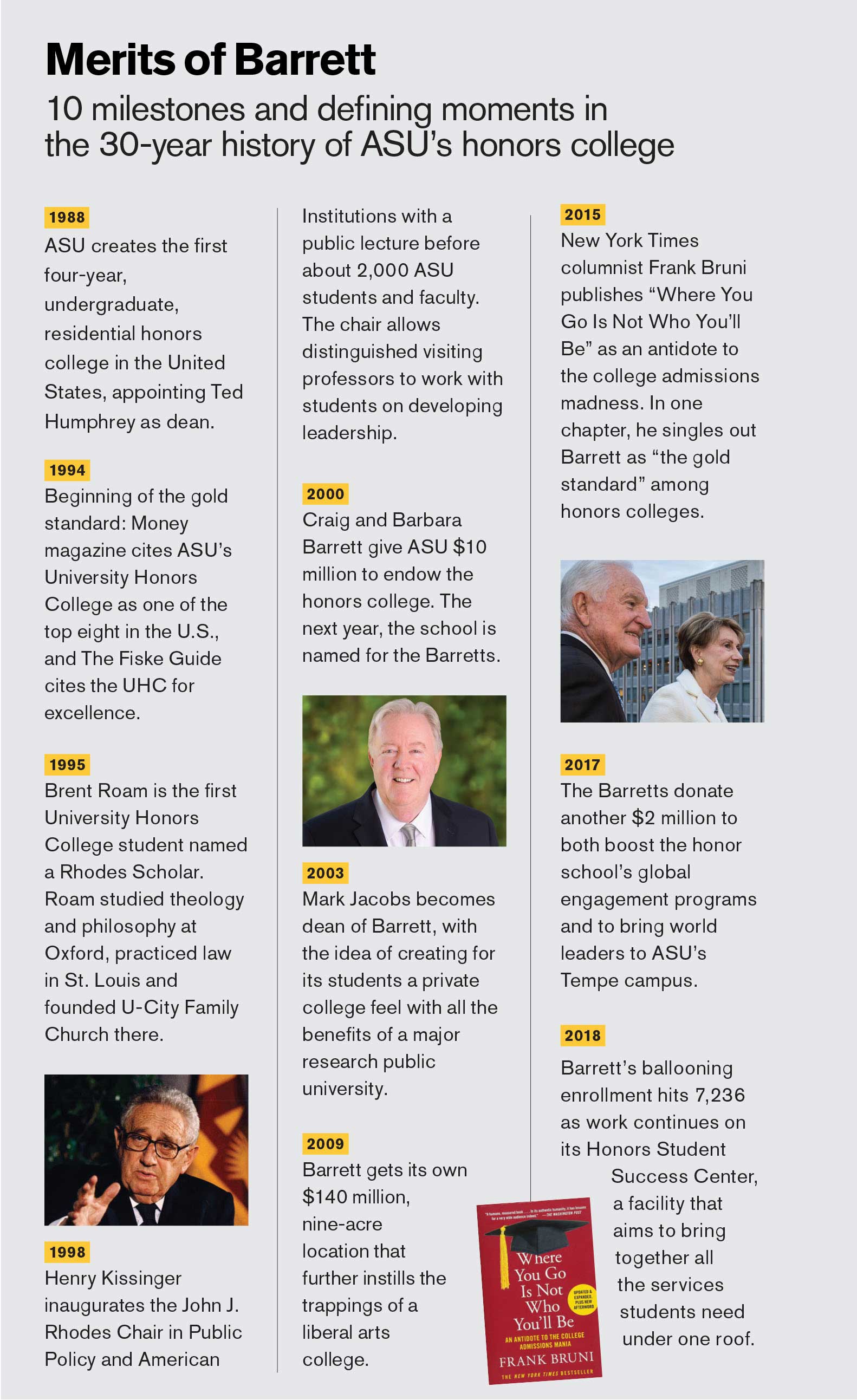

Fast-forward to 2000. She and husband Craig Barrett, the former CEO of Intel, endowed $10 million to ASU’s honors college, impressed by its success.

The school bearing their name is now renowned as the gold standard of public honors colleges, one to rival Ivy League universities and a model emulated around the world.

Barrett, The Honors College also has been transformed by the vision of ASU President Michael M. Crow and Mark Jacobs, who both left prestigious East Coast schools to create new models at ASU.

“It’s become the crown jewel of the university,” ASU benefactor Tom Lewis says of the honors college.

Culture change

Barrett welcomes incoming students to the community with a weekend at Camp B in Payson or Camp B-Town in Prescott to connect with new advisers, faculty, peer mentors and one another over glow sticks and s’mores. Photo by Tony Long

ASU’s honors college, established in 1988, had existed for 15 years when Crow first contacted Jacobs about leading it. But, Jacobs admits, “I didn’t know what an honors college was.”

He also didn’t know that would actually help him land the job as dean and serve him well as he remade the school during the last 15 years.

Crow became ASU’s president in 2002, a year before Jacobs arrived, with the idea to create a New American University. Crow had been Columbia University’s executive vice provost and knew that ideas could take root more quickly at ASU without pushing against 350 years of history and tradition.

“He had a vision no one else had,” Jacobs says, which was modeling Barrett as an innovative, interdisciplinary four-year residential college within an 80,000-student public research university.

Jacobs was an associate provost at Swarthmore, a private liberal arts college outside Philadelphia standing on tradition, and resistant to risk and change. Meanwhile, Crow wanted Jacobs to use his own ideas about what worked.

“It’s been exciting for that reason,” Jacobs says.

At first, ASU tried to play up the honors college’s prestige by targeting out-of-state students, but the goal was always to become the top choice for the state’s smartest students. Attracting in-state learners, who pay about one-third the cost of a small private college, makes it more likely they stay in Arizona after graduation.

“We were attempting to alter a culture,” Crow says about the entire university. “I hope the faculty here feel like they can advance any idea.”

Today, two-thirds of Barrett students come from Arizona. ASU and Barrett also produce as many Fulbright scholars as the Ivy League schools, and nearly four of every 10 Barrett alums attend graduate school immediately. About one-third of graduates enter the workforce, grabbing jobs at widely diverse companies such as General Motors, Microsoft, Boeing, Starbucks and Google.

“Nobody’s flipping burgers,” Jacobs says.

Barrett is home to big aspirations. Rachel Geiser (left, laughing with Prathima Harve during their advanced biochemistry class on the Tempe campus) is a senior double majoring in biochemistry and political science with the goal of becoming a surgeon and public health researcher. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

Student focus

Barrett graduates from earlier years almost seem like they don’t recognize the school when they visit today.

“The growth of the organization, the number of students benefitting, the influence on the broader education [at ASU], it’s astounding,” says Christopher Jaap, a 1995 graduate who launched Ridgeline Law Office in San Francisco in 2017 and established a scholarship for ASU honors students with a passion for sustainability. Barrett, he remembers, “opened my mind in a classic liberal arts way.”

Barrett also prides itself on providing a life experience, not just an educational experience. In 2009, the school opened a seven-building, $140 million complex spread over nine acres. Instead of occupying two floors in an existing residence hall, the honors college now owns the southeast corner of the Tempe campus.

This allowed Barrett to not only create its own dorm, where most students spend their first two years, but also honors classrooms, a separate dining hall and a refectory right out of Harry Potter and Hogwarts.

The new campus “took it to a whole other level of interaction for students,” says Kristen Joy Hermann, a senior associate dean for student services at Barrett.

Barrett students now constitute 18 percent of ASU’s freshman class, and they typically take two-thirds of their classes outside the honors college.

It’s all part of the “extra” that students say is one of their favorite aspects of Barrett — an oasis that allows them to find their passion. The whirlwind experience includes participation in everything from conducting original research to meeting personally with international leaders. There’s even a monthly breakfast with Jacobs.

Prospective students have taken note. Over the past 10 years, applications have more than tripled to 4,300 and enrollment jumped from 2,800 to more than 7,200 spread across four metro Phoenix campuses. In just 30 years, Barrett now has more students than Harvard.

The enrollment surge has not lowered academic requirements. Students still need to complete a thesis before they graduate, an unusual undertaking for an undergraduate. But it allows students to compete for various awards they also tend to win.

In 2017, Barrett was one of only four U.S. institutions to graduate Churchill, Marshall and Rhodes scholars in the same academic year. Indeed, over the past 10 years, Barrett has been among the top 10 universities producing Fulbright scholars.

“In the honors world, Barrett really is the gold standard; it’s not just a marketing slogan,” says Nicola Foote, vice dean and the newest member of Barrett’s administration.

Barrett is not just about classrooms. Grant House, a sophomore majoring in exercise and wellness, is also an elite-level ASU swimmer. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

Be like Barrett

Prior to this year, Foote had been an associate dean at Florida Gulf Coast University, where she was responsible for building the school’s honors college. She admits to using Barrett’s model to craft her school’s program.

Since stepping onto the ASU Tempe campus in the fall, Foote has seen behind the curtain, experiencing the innovation at Barrett up close and diving into attempts to improve the college.

She has quickly gone from copying Barrett’s methods to hosting tours for teams of officials from around the country who are anxious to emulate Barrett’s gold standard.

That slogan came from an unexpected source — New York Times columnist Frank Bruni, who wrote a book in 2015 about the mania surrounding college admissions. In “Where You Go Is Not Who You’ll Be,” Bruni devoted most of a chapter to ASU and the experiences of two Barrett graduates.

After the book came out, Jacobs contacted Bruni and provided more details about the school. Bruni was so impressed he praised the school in a column: “Barrett combines the intimacy and academically distinguished student body of a Swarthmore with the scale, eclecticism and sprawling resources of a huge university. It’s two experiences in one.”

Bruni also updated his book to include Barrett’s top ranking in John Willingham’s “A Review of Fifty Public University Honors Programs,” adding Barrett “is widely considered the gold standard.”

Today, one of Barrett’s biggest fans is Tom Lewis, an Arizona resident and ASU benefactor who graduated from the University of Kentucky.

In 2001, Lewis started a foundation to help fund top students in Arizona. While the recipients could go to any college — and they went as far away as Stanford, Duke and the Ivy League universities — Lewis started noticing more and more ended up at Barrett. “The best students want to go to the best schools,” he says.

So Lewis changed the scholarship, requiring students to attend Barrett. Then in 2015 he donated $23.5 million to create Lewis Honors College at Kentucky.

“It will be very much patterned after Barrett,” Lewis says, admiring not only the quality of Barrett but also how the college helps Arizona retain the state’s best and brightest. “They contribute back to the growth and prosperity of the entire state.”

Barrett also provides extensive mentoring. Dwayne Martin-Gomez reviews work with Allison Williams, his Barrett thesis mentor and program manager of research at the ASU Center for Health Promotion. Photo by Jarod Opperman/ASU

Future view

Barrett continues setting the trend for honors colleges at U.S. public universities.

“The tough work of the beginning has been established, but inertia doesn’t help quality,” says Barbara Barrett, currently the chair of Aerospace Corporation.

“Academics aren’t known for being nimble,” she adds. “At the honors college, innovation is the byword.” U.S. News & World Report agrees, ranking ASU as the nation’s most innovative university, ahead of MIT, Stanford and Carnegie Mellon, among others.

Barrett and her husband committed another $2 million to the honors college in 2017, expanding the school’s international program to bring the world to Tempe. In 2018, for example, Vaira Vike-Freiberga, the former president of Latvia, was a scholar-in-residence at Barrett, staying on campus for weeks to guest lecture in honors courses and meet with students in small groups.

“We want to get young people familiar with the global environment,” Barbara Barrett says. “This is the world they will be working with in the future.”

Next up: construction of an Honors Student Success Center. As part of the university’s Campaign ASU 2020, Barrett is seeking to build a one-of-a-kind facility among honors colleges, a single building that will house all the services students need under one roof. Plans include advisers, writing center, national scholarship office and more.

Barrett is raising its standard.

Written by Wayne D’Orio. D’Orio is an award-winning former editor-in-chief of Scholastic Administrator properties has written about education for The Atlantic, Wired, Pacific Standard and The Hechinger Report.

This story originally appeared in the winter issue of ASU Thrive magazine. Top photo collage by Sarah Horvath, Ellen O’Brien and Jarod Opperman/ASU

More Sun Devil community

Career support for students and alumni

At ASU, career preparation is built into the academic journey. Across disciplines, students and alumni access coaching, internships, recruiters, networking events and industry insights designed to…

From learning to leadership

Story by Bret HovellThroughout their careers, ASU graduates achieve success in almost every industry imaginable. By embracing ASU’s dedication to lifelong learning, these three alumni have created…

Master the next level

Story by Amanda LoudinIn today’s job market, certainty is rare. Shifting economic indicators, evolving industries and rapid technological change have students and professionals alike asking the same…