More than 130 years ago, a small community of settlers in a remote northern Arizona valley erupted into a frenzy of ambushes, murders and massacres.

In one five-year period during what has come to be known as the Pleasant Valley War, 18 people were killed and four were wounded by lawmen, Apache raids, vigilantes and their fellow ranchers.

The story of the American West is rife with violence, but, until now, no one has delved into the psychological effect of living constantly under the threat of death.

Western movies don't tell us what happens after the sun sets and the story fades to black. In historian Eduardo Obregón Pagán’s new book, "Valley of the Guns: The Pleasant Valley War and the Trauma of Violence," a character that stands in the shadow of all Westerns finally comes out into the light: traumatic stress disorder.

“We never see the messy aftermath,” said Pagán, Bob Stump Endowed ProfessorPagán holds a faculty appointment in the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences' School of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies. of History at Arizona State University. “Everybody involved in this conflict — everybody I could trace — they were indelibly marked by the violence here in tragic ways. Suicides later on. Women took their lives, ended up in insane asylums. Many of the men became alcoholics and died because of that. … We never talk about the aftermath of violence in the West, but everyone was affected, in very negative ways.”

New College Associate Professor Eduardo Obregón Pagán, author of “Valley of the Guns: The Pleasant Valley War and the Trauma of Violence,” discusses how a small Arizona settlement between 1881–1892 suffered numerous gunbattles with Apaches and other settlers. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Homes built like fortresses. Men armed to the teeth, at all times. The closest neighbor a reservation of thousands of angry Apaches, pushed to their limits. Outlaws and rustlers who had been chased out of other states. Lawmen who shot first and asked questions later.

Stir all these elements together in a secluded locale and you'll get scenes like these:

A lone sheriff serves a warrant. Twenty seconds later three men are dead, one lies wounded and a sobbing woman stands splattered in blood, cradling a screaming infant.

A request for supper at a remote ranch erupts into a gunfight with two men shot dead and two others crawling, wounded, for days.

And so it went, for years, hammering psyches.

Discouraging words: Conversations of the Pleasant Valley War (taken from 'Valley of the Guns')

“Good morning. Who are you looking for?”

“You, you son of a bitch.”

Gunfire erupted.

Video by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

Gradual beginnings

The Pleasant Valley War is an extremely complicated story, too much so to be condensed neatly into an article-length narrative. There were no good guys and bad guys. Almost completely unknown outside of Arizona, what is remembered about the saga today is myth, not fact.

“There’s so much mythology that layers these stories,” Pagán said. “A lot of what we live with in the modern age is really the mythology.”

It wasn’t a feud between the Graham and Tewksbury families. It wasn’t a conflict between cowboys and sheepherders. And it wasn’t Mormons versus non-Mormons. Or ranchers and rustlers.

It was everybody against everybody else.

“It’s not a triumphant narrative,” Pagán said. “It’s a struggle between those who were trying to make an honest living and those who were trying to make a dishonest living, and in the process a lot of lives were lost.”

The settlers were mostly single men, ranging in age from their early 20s to early 50s. They came from New York City, the Midwest, Texas and Tennessee. A few of the native languages spoken were Swedish, French, Polish and Spanish. Some had fought in the Civil War or the Indian Wars. They were small-time ranchers living far from civilization. Perhaps no more than 250 people were settled in the 7,600-acre Pleasant Valley in 1880. Everyone knew each other.

“Life and difficult circumstances led them to make choices,” Pagán said. “Those choices led to other choices, and it started to spin in different directions. Eventually those choices came into conflict with each other. … I try to tell a human story versus white hats versus black hats.”

The Graham family is a perfect example. They weren’t bad kids when they left the farm in Iowa, Pagán said. They grew up in a religious household. They went to California with stars in their eyes and ended up in Arizona with some of that glint dimmed.

It was a question of survival. It wasn’t that they pulled bandannas over their faces suddenly and immediately headed out on a moonlit night to steal cows. It was more of a case of a friendly face riding up one day with an offer along the lines of, “You mind if I leave these cows here for a few days?”

The Pleasant Valley War is often referred to as Arizona’s Hatfield-McCoy feud, with the Tewksbury clan facing off against the Graham family.

“The historical evidence simply does not support these claims,” Pagán said. “(It) was larger than both sets of brothers, and something that lay beyond the Grahams or the Tewksburys compelled the settlers to turn on one another.”

In 1882 the Apache raids and rustling began. Litigation amongst the settlers started the following year. The killing began in 1887 and continued for five years.

Why did an isolated settlement in a remote part of northern Arizona ultimately turn on itself with murderous violence?

Pagán calls it a place sitting at the “crossroads of violent economies.”

Pleasant Valley, Young, Arizona. Young is a ranching community about 150 miles northeast of Phoenix in the Tonto National Forest. It played a central part in the bloody events of the 1880s. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

A time and a place

“For me, the geography tells you almost everything you need to know about the story,” Pagán said.

Young, Arizona, is as isolated today as it was in the 1880s. The town sits in the middle of a national forest. There are no paved roads leading there. It’s situated about eight miles from the western edge of the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. The soil isn’t good enough for farming, which automatically makes it cattle country.

“There’s no natural barrier that separates the western border (of the reservation) from Pleasant Valley,” Pagán said.

The valley also sat at the crossroads of ancient Apache raiding trails, which swept from southern Colorado and Utah far down into Mexico. It lay smack-dab in the middle of a rustling corridor before anyone settled there. The Apache raided cattle in Mexico and sold them to the Navajo long before ranchers moved into the valley.

The Apache never agreed to be “pacified” until 1872–73. They were highly mobile people. They ranged down into Chihuahua, Mexico, and as far west as California, raiding and trading. Within their culture, status and honor was gained by their abilities in these areas.

“It was difficult for that first generation to switch gears,” Pagán said. “Terribly, terribly difficult, on that level alone, just to ask a culture to completely change their way of life that they had known for centuries.”

Another problem was corruption. The government contracted private businesses to supply the Apache with blankets, food, tools for farming and other goods they needed. When goods made it to the reservation at all, the people were shorted by corrupt agents, or were provided with substandard supplies.

“When the first winter comes along and there’s no food and there’s no blankets, what are you going to do?” Pagán said. “You’re going to do what you’ve always done. You go hunting. That means you go off the reservation.”

About 7,000 to 8,000 Apache lived on the White Mountains reservation.

“This is a land they know very well,” Pagán said. “They’re skilled hunters. You have a handful of soldiers who are supposed to keep watch over thousands of skilled hunters. It’s impossible. … There are outbreaks.”

Around 1876–77 the first settlers moved into the valley. The first outbreak exploded in 1881.

An Apache cultural value was stealth. You never knew when they were coming. But they didn’t attack at night. That was another cultural value.

The night belonged to the rustlers.

Horses get an afternoon drink at a ranch's watering hole in Young, Arizona, 150 miles northeast of Phoenix. Photo by Charlie Leight / ASU Now

Discouraging words: Conversations of the Pleasant Valley War

At a ranch, visiting cowboys asked for supper, a customary thing to do on the range.

“No, sir! We ain’t running no hotel here.”

“(Racial epithet)”

And bullets started to fly.

Cowboys and rustlers

In cattle country, “theft was a problem,” Pagán said. “An enormous problem. … If you lose your livestock, you lose your livelihood. If you lose your livelihood, you pack up and leave. There’s nothing left for you.”

The price of beef was on the rise, leading outside investors to jump into ranching. A Texan outfit called the Aztec Land and Cattle Company drove immense herds into northern Arizona. Their employees, dubbed the Hashknife cowboys, were a rough bunch. Frequently on the run from the law, they had no compunction about shooting each other or anyone else.

Holbrook became a regional rail terminus, where cattle were shipped back East. Cowboys and sheepherders, pockets full of cash after delivering livestock, crowded into Holbrook’s saloons and shot up the town. In 1886, 26 men were killed by gunfire in a town of only 250 full-time residents. The town had such a bad reputation the Salvation Army designated it as a special target for evangelizing.

Cowboys had a lousy reputation in the Old West. They were rootless, often used aliases, and they were usually believed to be involved with rustling.

“If you look at the documents from the 1870s and 1880s, to call someone a cowboy was an insult,” Pagán said. “It was a fighting word. A cowboy back then had the reputation of being a thief. ... If you liked someone, you called them a cowherder.”

Hashknife cowboys in particular were notorious. When not poaching cattle from small ranchers, they stole from their own herds. They also went about heavily armed. The Apache may have been confined to the reservation, but that didn’t stop cattle rustling.

“As the native communities began to agree to stay put within reservations, and white settlers started to come to Arizona, that economy didn’t go away,” Pagán said. “It simply changed players. And there were enterprising Americans who realized, ‘Oh, there’s opportunity here.’ There’s lots of records white Americans got involved in this trading economy.”

And they did so at night, when the Apaches were not about.

Hashknife cowboys, Arizona, 1880s. Photo courtesy of Arizona Collection, Arizona State University

Settlers

“By night, you can’t get a good rest because that’s when the rustlers come out,” said Pagán, describing the daily life of a Pleasant Valley settler in the 1880s. “You’re worrying about sneak attack by day. You’re worrying about your livestock at night. How on earth do you get a decent rest? At any point? It might seem like a silly question to ask, but it has an impact over time.”

It wasn’t the suburbs. People lived next to dependable waterways, of which there are few. Living close meant being half a day’s ride away.

“You can’t circle the wagons,” Pagán said. “You can’t depend on each other in times of stress. When the Apaches come raiding through, you’re on your own. This is a highly tense environment.”

John Tewksbury Sr.’s cabin still stands, not in Young, but at the Pioneer Living History Museum outside Phoenix. The cabin’s architecture gives vivid insight into daily life.

The logs it is built of are about 11 inches thick — sturdy enough to stop a bullet. Every wall has two gun ports. There are gunports at the head — and foot — of the bed. There’s a gunport at the kitchen table. There are gunports by the fireplace.

“There is not a spot in that cabin where you’re not more than a couple of strides away from being able to defend yourself,” Pagán said. “Or, on the other hand, were those gunports to remind you that on the other side of that wall was death and danger? That becomes important in my trying to reconstruct what life was like in this small community. … There’s nowhere in that cabin that doesn’t remind you that you’ve got to stay alert because you never know when the Apaches are coming.”

Middleton ranch, Pleasant Valley, Arizona. A day after a notorious shootout that left two dead and two wounded, the ranch was burned to the ground on Aug. 10, 1887.

Prescott was the county seat and where the law was. It was three days’ hard ride from Pleasant Valley.

The valley was a different community than Globe, Prescott or the Mormon towns on the Mogollon Rim. There was no town council or elder statesman or offer of an olive branch, no one to say, “Hey, let’s step back from this and cool down for a moment.”

“You’re on your own,” Pagán said. “What that does is produce a community of fear. That’s what existed in the early 1800s was this small community — and I really mean small — really no more than about a dozen households during this time. … How did the relentless anticipation of surprise attack wear on them day after day, year after year?”

Pagán worked with colleagues in psychology, physiology and biology to discuss the science of how the brain works under trauma.

“The impact of trauma, of violence, of fear — and how that impacts our abilities to function on a normal, rational, reasonable basis: even something as simple as your ability to just get a normal night’s sleep over time,” he said.

Nature never intended the fight-or-flight response to be a long-term solution to crisis. “That neurochemical response that quickens the blood flow and stimulates heart and nerves becomes toxic over time,” Pagán wrote. “The acute stress response can turn into an acute stress reaction.”

Symptoms include anxiety, restlessness, anger, depression, difficulty concentrating and sleeping and overreaction to circumstances.

Discouraging words: Conversations of the Pleasant Valley War

Hashknife cowboys join a search party heading to Pleasant Valley.

“There’s a war going on down there,” a range detective warned.

Shot back one cowboy, “Maybe we’ll start a little old war of our own."

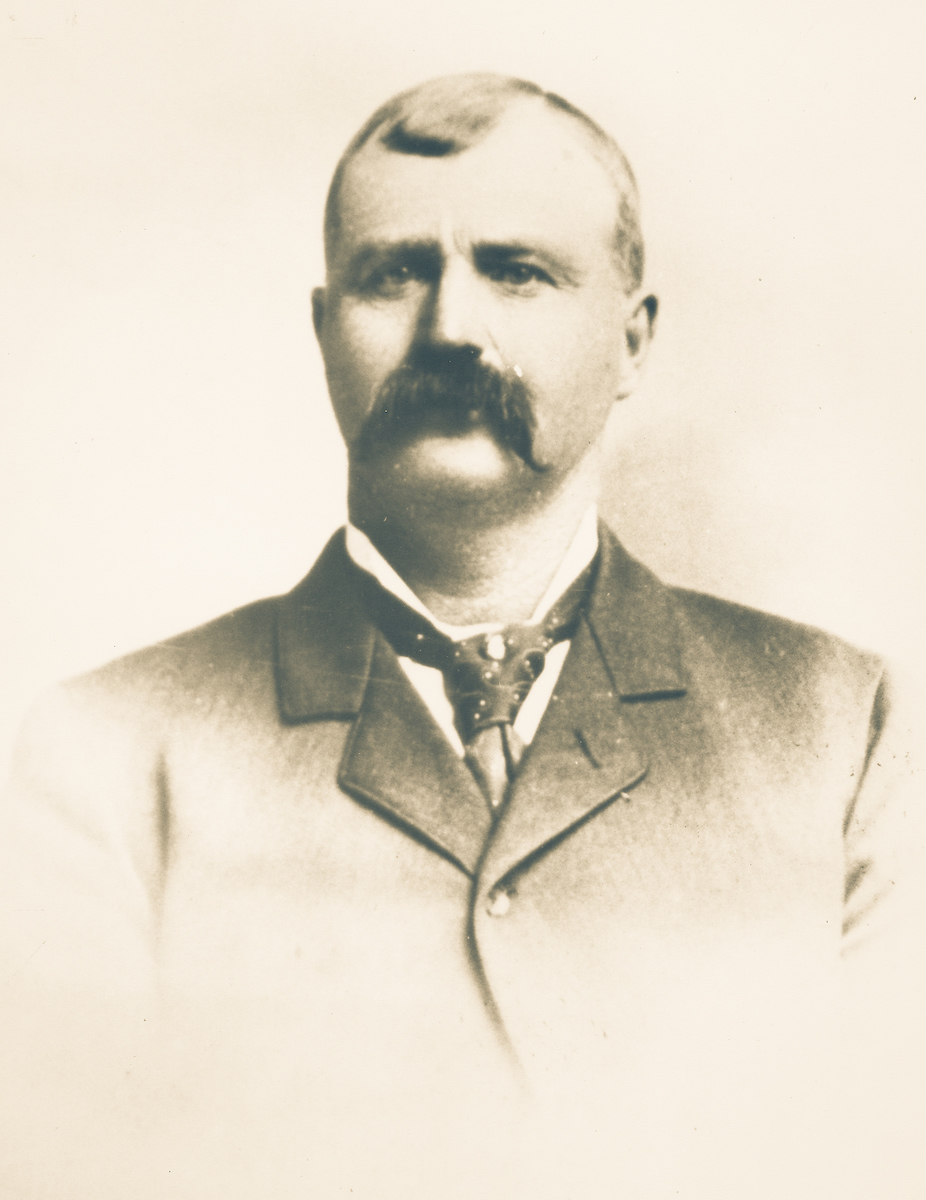

William Mulvenon, sheriff of Yavapai County, 1887. Mulvenon was a typical lawman of the Old West, ready to shoot and more than willing. Photo courtesy of the Arizona Collection, Arizona State University

Litigation

Between 1883 and 1888, about two dozen households in the valley participated as complainants, defendants or witnesses in about 30 court hearings.

“The law in a lot of ways was just as much a problem,” Pagán said. “Part of the problem with this community was the Grahams tried to use the law to intimidate their neighbors. … They issued the lion’s share of lawsuits against their neighbors. 'You stole my cattle.’ ‘You stole my cattle.’ They named everyone they could possibly name. Here’s the problem with that: The legal system was such that for every lawsuit, there were three hearings.”

There was a preliminary hearing, grand jury hearing and a court hearing. Attending court in Prescott meant a three-day ride — each way — from the Tonto Basin.

“What that means was you were either in jail after the indictment or if you were out on bail, you were constantly making that trip back and forth to Prescott,” Pagán said. “The point is, this is significant harassment. If I sue you, it’s not just a one-time court appearance. You were making that trip back and forth to Prescott three times. It’s a real pain, and it’s not just you. They named witnesses. So half the community is now going back and forth to Prescott.”

Hiding behind badges

If there was a conflict, it was between those who were trying to protect their livestock and the law, and those who were trying to make a quick buck off their neighbors.

“That was the issue, and that’s why the law would come sweeping in,” Pagán said.

Lawmen were not Officer Friendly. They weren’t trained, at all. They simply pinned on a badge and strapped on a gun.

“In every situation they rode into, their guns were raised and their fingers were on the trigger and their weapons were primed,” Pagán said. “Unless you showed every sign of yielding, they would shoot. That was the law in Arizona. … The people who were shot and killed did not yield fast enough.”

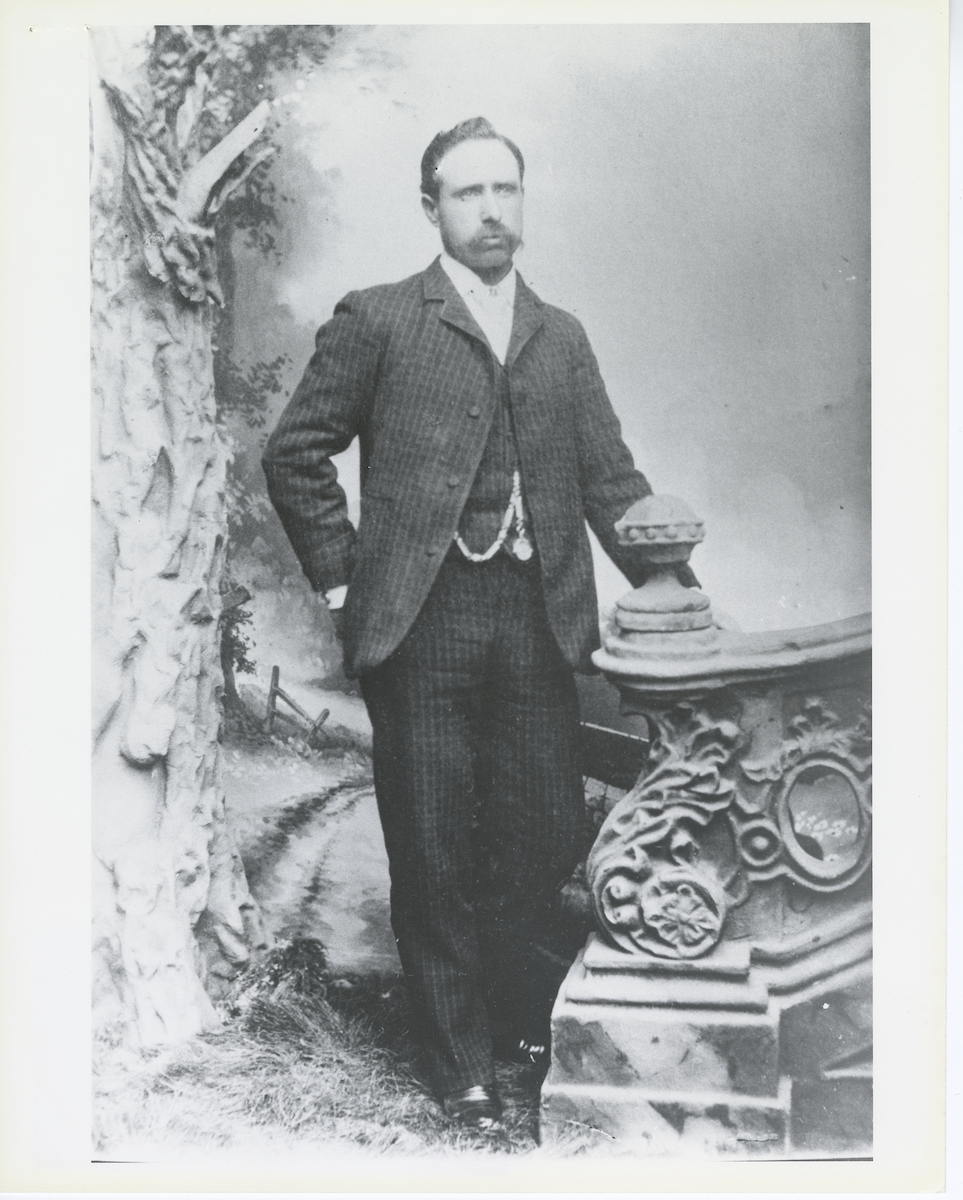

Commodore Perry Owens, the Apache County sheriff, “would shoot not only at the drop of a hat, but before the hat was dropped,” an Arizona newspaper quipped. Owens killed three members of a rustling family and wounded a fourth in a 20-second gunbattle in Holbrook. He was alone and he simply saw a weapon through a doorway.

William Mulvenon, the sheriff of Yavapai County, went up to the valley to make arrests in recent killings. When he lured two suspects into a trap, he stepped into the open and ordered them to put up their hands. They yanked on their reins to wheel their horses around, and the sheriff opened fire.

It was the death of a settler in a case of mistaken identity during an attempted arrest that lit the whole powder keg. Throughout the conflict, lawmen killed more people than did Apaches, settlers or vigilantes.

Commodore Perry Owens, sheriff of Apache County, 1887. Owens killed three men and wounded a fourth in a 20-second gunbattle in Holbrook. He was alone. Photo courtesy of the Arizona Collection, Arizona State University

The unspoken price

“What it is in my mind is a darker story about the settling of the American West than what we’ve often told ourselves,” Pagán said. “This is a story of a small community that cracked and turned on itself within this pressure cooker of violence.”

After the chronic theft, competition from corporate cattle outfits, legal complaints, lynchings, executions by masked men, torched ranches, ambushes and shootouts, the constant exposure to violence and death left a profound emotional impact.

“Eighteen men in the Pleasant Valley War lost their lives violently, and of those who survived the conflict, some were permanently disabled,” Pagán wrote. “Others were stalked by depression, insanity and suicide.”

While there is no written record of how those times affected the White Mountains Apaches, one famous Chiricahua Apache’s reflections at the end of his life were recorded.

Geronimo — whose own children had been killed by soldiers — discussed when he was 77 how nightmares born in guilt caused him to wake in terror, years after he himself had killed children. “Now I wake up groaning and very sad at night when I remember the helpless little children,” he said, quoted in Pagán's book.

The story of the Pleasant Valley War faded from view, even during the Cold War, when the myth of the Old West, where good vanquished evil, was resurrected to serve national narratives.

“The Pleasant Valley War as history, instead, does not provide such affirmation,” Pagán wrote. “Rather, it reveals sides of our national story, if not the human experience, that we would rather not see. … There is no great story of chivalric behavior, or right and wrong, on which to hang the themes of the Western. There were only desperate souls behaving most desperately.”

Gravesites of the Pleasant Valley War in Young, Arizona. Note the dates of death. Photo composite by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

4 ASU researchers named senior members of the National Academy of Inventors

The National Academy of Inventors recently named four Arizona State University researchers as senior members to the prestigious organization.Professor Qiang Chen and associate professors Matthew…

Transforming Arizona’s highways for a smoother drive

Imagine you’re driving down a smooth stretch of road. Your tires have firm traction. There are no potholes you need to swerve to avoid. Your suspension feels responsive. You’re relaxed and focused on…

The Sun Devil who revolutionized kitty litter

If you have a cat, there’s a good chance you’re benefiting from the work of an Arizona State University alumna. In honor of Women's History Month, we're sharing her story.A pioneering chemist…