Gila River Indian Community members see traditional house designs come to life

Family is the most important thing to people who live in the Gila River Indian Community, and the houses they live in should reflect that reality.

That was the key concept that members of the community told a group from Arizona State University earlier this week. About 30 community members participated in an idea session with several graduate students and an architecture professor to design new housing that would be culturally relevant.

Wanda Dalla Costa, an architect and Institute Professor in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, has been working with the Gila River Indian Community on the concept for about three years. She calls it “design sovereignty.”

“They’ve been residents of the desert for thousands of years, and they’ve figured out how to live in the climate,” said Dalla Costa, a member of the Saddle Lake First Nation in Alberta, Canada. Dalla Costa was the first First Nations woman to become a registered architect in Canada.

“I don’t use the word design — it’s co-design, because I’m not living there, they are living there. Even though I am indigenous, it’s not my culture.”

Thousands of years ago, the Gila River tribal members built dwellings with thick adobe walls to protect them from the heat. But in the 1960s, the federal government began providing standardized housing to reservations, which wasn’t designed for the desert climate. The Gila River Indian Community wants future housing to not only be culturally relevant but also more energy efficient.

Last year, Dalla Costa met with several Gila River residents for the first time to talk about what their houses should look like. They produced about half a dozen designs, ranging from about 1,600 to 2,600 square feet.

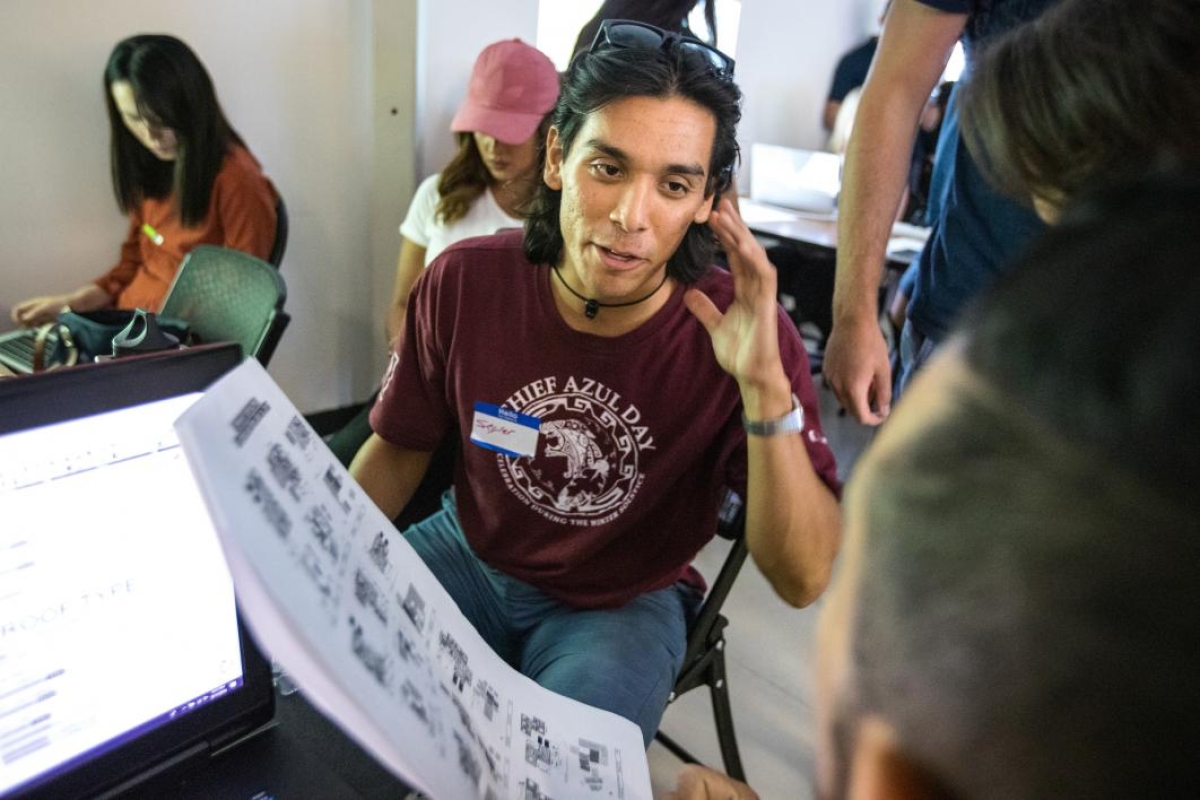

On Tuesday, Dalla Costa gathered the community members together with about 30 ASU graduate students in the architecture, business administration, construction and American Indian Studies master’s degree programs. In a classroom at the Huhugam Heritage Center, the residents divided into groups, took those initial designs and talked more specifically about what they wanted. The students offered different wall, roof and window options, which were then visualized in a three-dimensional computer program.

Skyler Anselmo, a 23-year-old member of the community, said that many times, more than one family lives in a house.

“We grew up sharing space,” he said. “The houses we have now are crowded together and there’s no synergy.

“The foundation of our culture is to share and prosper together,” said Anselmo, who works in Sacaton in the AmeriCorps program.

Dalla Costa told the groups they could push the envelope, and Anselmo’s group did. They designed a house with a large, open, round central family room, with other rooms coming off of it like spokes.

The community members were nearly unanimous in their desire for an outdoor cooking area, as well as a shaded patio and a play area. They were also interested in traditional features that are sustainable, like a rainwater catcher.

And everyone wants a garden.

“It’s part of our history, when we were self-sustaining,” Anselmo said. “It goes back to the roots of our culture when we grew our own food.”

Sky Dawn Reed, who earned a master’s in science and technology policy degree at ASU and now works in the planning department of the Gila River Indian Community, said the design should be flexible.

“We should think about making the houses solar-ready,” she said. “It might not be doable now, but maybe we can do it later. It might even be far off, but we should be forward-thinking.”

Belinda Ayze, a graduate student in the American Indian Studies program at ASU, sat with an elderly resident and helped to facilitate her discussion about the design.

“I was asking her how she lived her life and how she cooked and if she wanted wheelchair ramps and bars in the shower,” she said.

“I asked why she wants a cooking area outside, and she said, ‘Food tastes better with fire.’ ”

Ayze, a Navajo, said the older residents she talked to wanted traditional adobe walls and doors that face east.

“I think it’s a good idea to make the houses the way they want and the way they’ve always dreamed of living with their families,” she said.

The goal is to train Gila River residents to build the houses. Last spring, ASU architecture master’s student Selina Martinez designed a traditional adobe shade structure, or “vatho,” which was constructed by a team of Gila River builders, led by master builder Aaron Sabori.

Dalla Costa hopes to come up with about six final designs, with one or two selected to go into construction drawings. Then a prototype would be constructed within the next year.

“The design belongs to you, and construction should belong to you because I know there is a long history of constructing your own homes,” she told the community.

Top photo: Members of the Gila River Indian Community look over several of the housing designs for the Gila River Indian Community in a collaboration between members of the community and graduate students from ASU schools of architecture, business, engineering and American Indian studies, at the Huhugam Heritage Center on Tuesday. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Environment and sustainability

A 6-month road repair that only takes 10 days, at a fraction of the cost? It's reality, thanks to ASU concrete research

While Arizona’s infrastructure may be younger than its East Coast counterparts, the effects of aging in a desert climate have begun to take a toll on its roads, bridges and railways. Repairs and…

Mapping DNA of over 1 million species could lead to new medicines, other solutions to human problems

Valuable secrets await discovery in the DNA of Earth’s millions of species, most of them only sketchily understood. Waiting to be revealed in the diversity of life’s genetic material are targets for…

From road coatings to a sweating manikin, these ASU research projects are helping Arizonans keep their cool

The heat isn’t going away. And neither are sprawling desert cities like the metro Phoenix area.With new summer records being set nearly every year — 2024 was the warmest year on record for…