'Slow earthquakes' on San Andreas Fault increase risk of large quakes, say ASU geophysicists

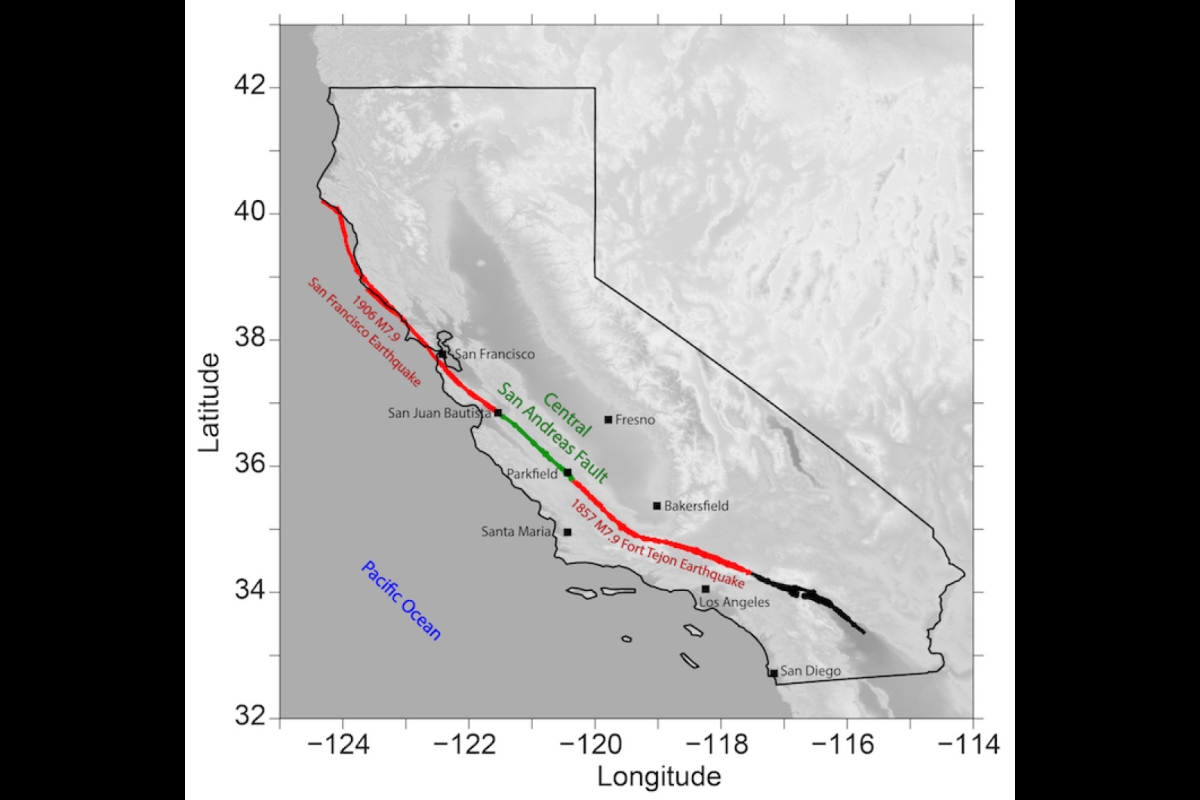

Geologists have long thought that the central section of California's famed San Andreas Fault — from San Juan Bautista southward to Parkfield, a distance of about 90 miles — has a steady creeping movement that provides a safe release of energy.

Creep on the central San Andreas during the past several decades, so the thinking goes, has reduced the chance of a big quake that ruptures the entire fault from north to south.

New research by two Arizona State University geophysicists, however, shows that the earth movements along this central section have not been smooth and steady, as previously thought.

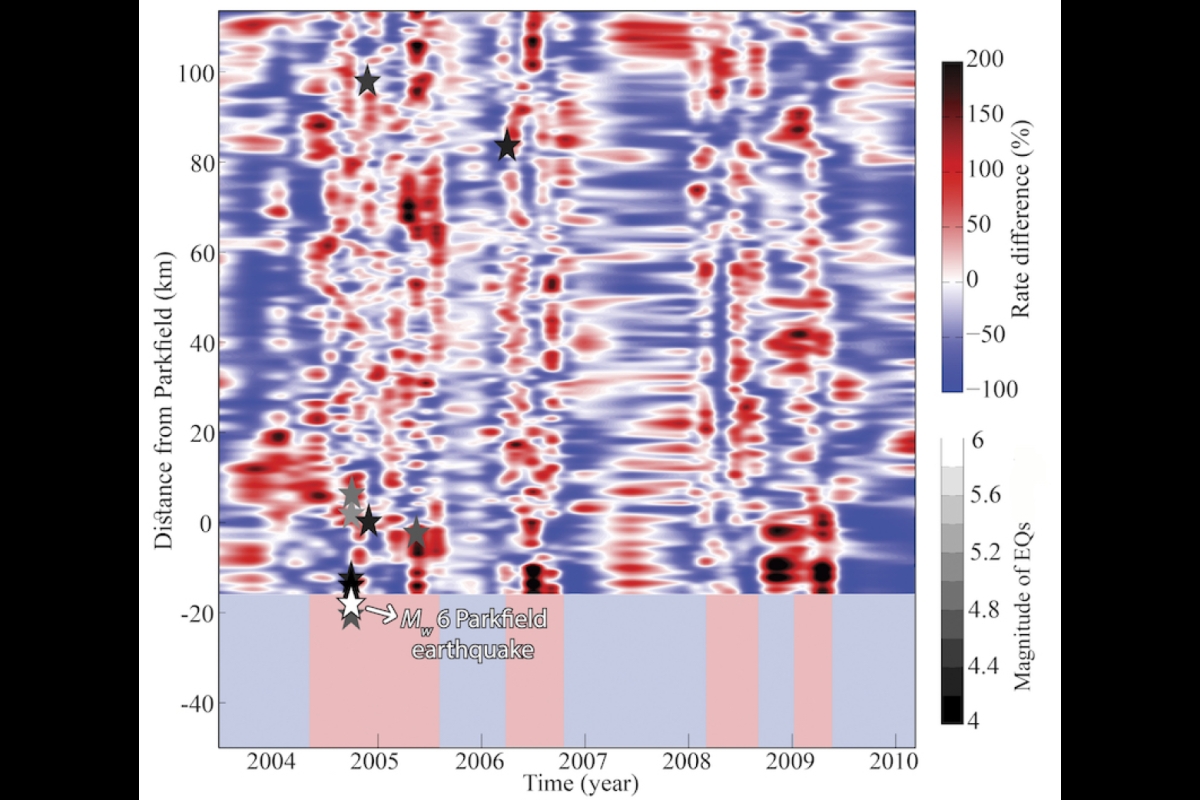

Instead, the activity has been a sequence of small stick-and-slip movements — sometimes called "slow earthquakes" — that release energy over a period of months. Although these slow earthquakes pass unnoticed by people, the researchers say they can trigger large destructive quakes in their surroundings. One such quake was the magnitude 6 event that shook Parkfield in 2004.

"What looked like steady, continuous creep was actually made of episodes of acceleration and deceleration along the fault," said Mostafa Khoshmanesh, a graduate research assistant in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE). He is the lead author of a Nature Geoscience paper reporting on the research.

"We found that movement on the fault began every one to two years and lasted for several months before stopping," said Manoochehr Shirzaei, assistant professor in SESE and co-author of the paper.

"These episodic slow earthquakes lead to increased stress on the locked segments of the fault to the north and south of the central section," Shirzaei said. He points out that these flanking sections experienced two magnitude 7.9 earthquakes, in 1857 (Fort Tejon) and 1906 (San Francisco).

The scientists also suggest a mechanism that might cause the stop-and-go movements.

"Fault rocks contain a fluid phase that's trapped in gaps between particles, called pore spaces," Khoshmanesh said. "Periodic compacting of fault materials causes a brief rise in fluid pressure, which unclamps the fault and eases the movement."

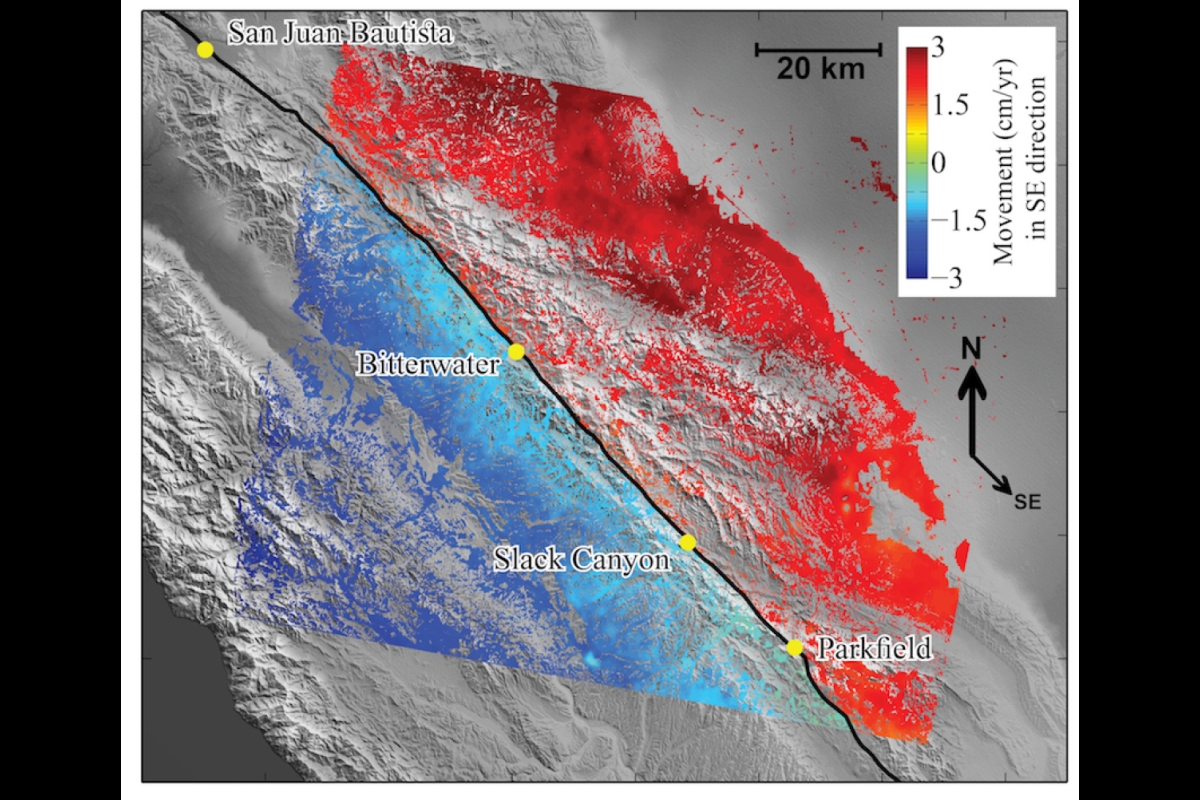

Looking underground from Earth orbit

The two scientists used synthetic aperture radar data from orbit for the years 2003 to 2010. This data let them map month-to-month changes in the ground along the central part of the San Andreas. They combined the detailed ground-movement observations with seismic records into a mathematical model. The model let them explore the driving mechanism of slow earthquakes and their link to big nearby quakes.

"We found that this part of the fault has an average movement of about three centimeters a year, a little more than an inch," Khoshmanesh said. "But at times the movement stops entirely, and at other times it has moved as much as 10 centimeters a year, or about four inches."

The picture of the central San Andreas Fault emerging from their work suggests that its stick-and-slip motion resembles on a small timescale how the other parts of the San Andreas Fault move.

They note that the new observation is significant because it uncovers a new type of fault motion and earthquake-triggering mechanism, which is not accounted for in current models of earthquake hazards used for California.

As Shirzaei explained, "Based on our observations, we believe that seismic hazard in California is something that varies over time and is probably higher than what people have thought up to now." He added that accurate estimates of this varying hazard are essential to include in operational earthquake-forecasting systems.

As Khoshmanesh said, "Based on current time-independent models, there's a 75 percent chance for an earthquake of magnitude 7 or larger in both northern and southern California within next 30 years."

Top photo: The southern San Andreas Fault slices across the Carrizo Plain in California. Both the northern and southern sections of the San Andreas have seen large destructive earthquakes, while the central section between north and south has remained largely quiet. New work by ASU geophysicists suggests the central section moves in a new way that makes big quakes more likely. Photo by U.S. Geological Survey

More Science and technology

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…