Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2017, click here.

Arizona State University scientist Rolf Halden jokes that his real job is to scare the public, but in the course of his work he has made the public healthier.

Starting at the beginning of September, the Food and Drug Administration will prohibit the sale of personal-care products containing prominent antimicrobials, including triclosan and triclocarban — prized for their antimicrobial properties. The ban is a direct result of Halden’s research, which started in 2002.

“I want to rattle people’s cages to make them aware of what’s happening in our world,” said Halden, director of ASU’s Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering and the lead author of the Florence Statement, a declaration signed by more than 200 scientists and medical professionals that laid out a convincing case against why these two antimicrobials are harmful.

“Oftentimes science is so detailed that the message can easily be lost, so I try to communicate what these things are about and why they’re important. They should be things we care about; otherwise, we shouldn’t be spending tax dollars on them.”

HaldenHalden is also a professor in the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, and a senior sustainability scientist in the Global Institute of Sustainability. has long contended triclosan and triclocarban are often ineffective in safeguarding the public from harmful microbes and, further, pose significant risks to human health and the environment by contaminating air, soil and water.

The FDA’s ruling only applies to consumer hand washes and soaps. The restriction does not extend to building and household products that are outside the purview of the FDA but still contain hazardous and ineffective antimicrobials sold throughout the U.S. and worldwide. Still, the FDA’s ruling is a major victory for consumers.

ASU Now caught up with Halden before his Aug. 29 Q&A, which will be livestreamed on ASU’s Facebook page starting at 11 a.m. Hosted by Knowledge Enterprise Development, the half-hour session will feature Halden discussing his work and answering audience questions.

Question: You’ve often said it’s your job to scare people. What do you mean by that?

Answer: I want to rattle people’s cages to make them aware of what’s happening in our world. Everything that people encounter on the shelves at the store they believe is safe to use. But if you look at the underpinnings of what products and materials get manufactured into commerce, there are very few safeguards. The thing to remember is that we should never turn off our common sense and we should always ask questions.

For example, if you have ants or pests in your house and you go to the store to buy pesticides to kill them — if you decide to use these chemicals, beware that they could possibly do harm to you as well. When things are very powerful, they can work both ways — for the good and for the bad. So it’s my job is to make people think just a little bit more about their health and safety.

Q: There is an assumption that the FDA will safeguard us from all things that are unsafe. Is that expectation too lofty or naïve?

A: I think overall the FDA is doing a pretty good job. There are also mechanisms that tend to push products and chemicals which are not necessary and which pose risks in certain environments. There are marketing mechanisms that tend to increase the desire to have certain chemicals or products, resulting in mass production. The more you make of a problematic chemical, the bigger the risk that it harms you or that it gets around in your house, your country or around the globe.

We have many examples of chemicals that travel places and do any harm. Keeping an eye on production and making sure they aren’t running out of rudder with respect to volume is important. If something is declared safe but only was deemed to be used by a few, while all of a sudden the chemical is widely produced and used by everyone, it ramps up everything, including the risk. So ultimately it’s the responsibility of the consumer.

A lot of people say they hate chemistry, although chemistry is the science that makes up everything. Chemistry decides on the way you look and live, and is linked to emotions and behavior. It’s a very, very powerful and certainly underappreciated scientific discipline.

Q: How big of a victory is the FDA ruling?

A: Ultimately it’s rewarding for the science community — to see the results of their labor and work that translates into something tangible. This is an example where the work of many people has resulted in a conclusion that can help us protect people better if we can reduce these types of chemicals into our living environment. Ultimately it’s a very rewarding situation, and it doesn’t happen very often. It’s not common that chemicals get removed from products in the United States.

We must also understand these chemicals are not entirely disappearing. The FDA only regulates a certain amount of products under their purview. It’s in a lot of other products: carpets, socks, shoes, and other things that can be impregnated with triclosan and other antibacterials. There is still a need for vigilance on the side of the consumer to know that something can be harmful and avoided unless it’s really needed. It’s only being banned in soaps because it’s all the FDA. can do. There is still a need to translate this ban to other products as well.

Q: How often does the FDA listen to scientists, and how often does it change its mind when confronted with scientific evidence?

A: The FDA is always listening and absorbing science. There is an intrinsic problem with the fact that there’s always knowledge, and that knowledge gained is eventually added on. As a scientist, we tend to think that recent studies are always more thorough and better designed and therefore are more reliable. Industry, on the other hand, tends to go back to studies that are older and oftentimes did not report any adverse effects. It’s often the job of the FDA to weigh in on this and reach a fair judgment that keeps people safe.

For everything we study, there are always studies that show there are potential problems. It’s a delicate process to decide whether or not the integration of these types of chemicals ultimately serves public health or not. The FDA reached the right conclusion in removing these antimicrobial chemicals from the market.

Q: Let’s discuss triclosan and triclocarban and the impacts they have on people and the environment.

A: Triclosan and triclocarban are chemicals that resemble in many ways the chemicals that we mass-produced and then banned in the 1970s. Things like DDTDichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) were produced as the first of the modern synthetic insecticides in the 1940s. It was initially used to combat malaria, typhus and the other insect-borne human diseases among both military and civilian populations. It also was effective for insect control in crop and livestock production, institutions, homes and gardens. comes to mind, and it was assumed to be safe at the time. We now know that this chemical is persistent and bio-accumulative. Once it gets stored into our body it stays with us for a long time. These are chemicals you want to avoid.

But we’ve done the opposite. We’ve really ramped up production and gone through millions of pounds. So for us now it is difficult to provide even a control sample of these chemicals because they are everywhere. They are in paints, carpets, sofas, and also get into the lab environment as unwanted contaminants. Nintey-seven percent of women in American have triclosan in their breast milk. It’s a chemistry that didn’t serve us well in the past and it needs to go away. It needs to be replaced with better chemistry, sustainable or greener chemistry that’s more compatible with nature. We should mass-produce products that do not destroy our environment.

Q: The ban will go into effect in September. Does President Donald Trump or any other entity have the power reverse this decision?

A: It would be undesirable to do so. This decision also involves a lawsuit and consent decree. So for that reason, this just isn’t a political move and is difficult to reverse in the United States. What we hope is that through the coverage of this ban other countries and nations will take a closer look at them.

Ultimately, we all live in one big bubble, our planet's atmosphere. When we ban a chemical here in the U.S. and it’s mass-produced in other places around the world, it still comes to us. We banned DDT in the 1970s, and it’s still being produced in other parts of the world. It actually travels atmospherically and comes back to visit and is detectable in everyone.

Q: Going forward, what’s the next problem or challenge you plan on tackling in this domain?

A: Triclosan and triclocarban and other antimicrobials are symptomatic only; we need to leapfrog from an old type of chemistry that has provided services but has come at great environmental cost. We need a new generation of chemicals.

It’s a difficult transition because we have built this pipeline that likes to take in fuel-based, non-recyclable resources. Ultimately, we have to make this transition because we are running out of the feedstocks we have used in the past. There are better alternatives. The challenge is to communicate the risk of existing chemicals and to build political momentum and the will to transition to safer and greener alternatives.

Q: What can consumers do on their end?

A: I would suggest they use common sense. Say if a chemical is advertised as killing a lot of things, it also probably poses risks to human health. If you decide to buy it, then it should probably be stored in a safe place. If you don’t need to have a product in your living space, or if you smell it all the time, it probably means you’re getting exposed.

For example, everybody loves new-car smell. Well, new-car smell is actually the plasticizers that come out of plastics and these chemicals are known to act as endocrine disruptors. So people need to change their mind-set about their sensory perception and what it means. If they can smell something that’s prominent, that should serve as a warning signal.

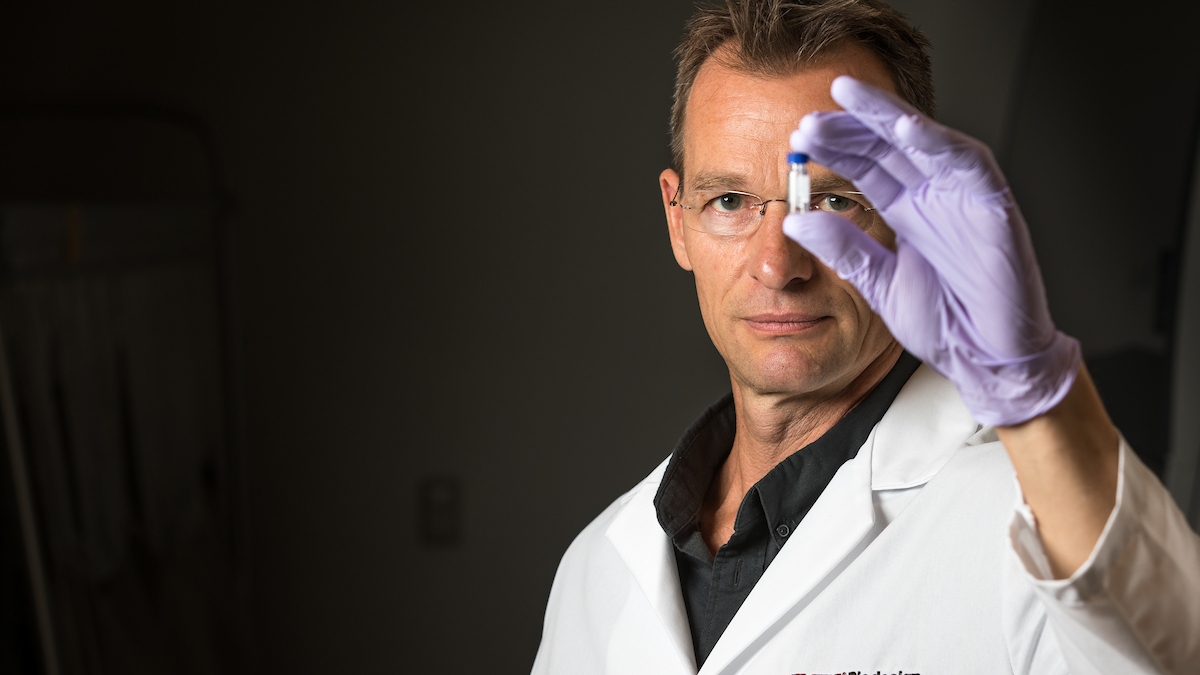

Top photo: ASU Professor Rolf Halden, director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at the Biodesign Institute, talks about his fight to get the FDA to ban two antimicrobial agents — triclosan and triclocarban — in one of the chemistry labs on the Tempe campus on Thursday. The ban takes effect in September for the chemicals' use in soaps. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…