Getting a space mission selected by NASA is like running a high-tech obstacle race as hard as you can for years on end — and there’s no guarantee you’ll win or even place in the final.

After a grueling five-year pitch, a team of scientists — led by Lindy Elkins-Tanton, director of Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration — recently completed the official NASA “site visit” for a proposed space mission to the metal asteroid Psyche. This moves the team members one step closer to finding out if their mission will be selected for NASA’s Discovery Program.

Psyche is an asteroid made almost entirely of nickel-iron metal. It offers a unique look into the violent collisions that created Earth and the terrestrial planets. Going to Psyche would be a planetary first because no space mission has ever visited a world like it.

But does NASA think the mission can be done? That depends largely on the results of the official mission “site visit.” The name is bland, but the reality can be daunting to the scientists and engineers involved.

A NASA site visit is an intense, highly technical, in-person review done by a select group of science, technical and industry experts. It is usually done at the institution that will actually manage the spacecraft. No detail is too small to delve into, and weaknesses in the mission’s concept, in its design, execution and science application are probed relentlessly. The reviewing team also assesses how well the mission personnel from different institutions work together under stress.

While 30 NASA reviewers descended on Space Systems Loral (SSL) in Palo Alto, California, for the nine-hour site visit, including a tour of SSL’s high bay where the Psyche spacecraft would be built, the team made final preparations for its presentations, months in the making.

Space System Loral’s satellite manufacturing facility in Palo Alto, California. Image courtesy of SSL

Elkins-Tanton, principal investigator of the Psyche mission, led the team of scientists, researchers and engineers from Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), SSL and several other universities and research institutions through the process.

“The most surprisingly thing about the site visit was its scale,” Elkins-Tanton said. “I thought it was overkill to start planning six months ahead, but it turns out that was almost not enough time. Presenting answers to these complex and technical questions about our mission really took the team of about 140 people many long and hard-worked days.”

For the site visit, the team delivered more than 400 pages of answers to NASA to further describe the details of the proposed mission to the asteroid Psyche, in addition to the formal in-person presentations to 30 NASA reviewers.

Jim Bell, planetary scientist in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the mission’s deputy principal investigator, said as the team gathered for a pre-presentation pep talk, “Today is our first critical event. Our second is the launch.”

Behind the scenes on the day of the site visit, specialized teams in the rapid-response room prepped for last-minute and impromptu NASA questions, while event managers double-checked guest lists and A/V equipment, set out VIP place cards and handed out name badges.

“There was so much energy in the air,” Elkins-Tanton said.

Psyche — a window into planetary cores

Every world explored so far by humans has a surface of ice or rock or a mixture of the two, but their cores are thought to be metallic, including Earth’s. These cores, however, lie far below rocky mantles and crusts and are considered unreachable in our lifetimes.

Psyche, an asteroid that appears to be the exposed nickel-iron core of a protoplanet, one of the building blocks of the sun’s planetary system, may provide a window into those cores.

Artist rendition of the surface of Psyche. Image courtesy of Peter Rubin/ASU

Psyche follows an orbit in the outer part of the main asteroid belt, at an average distance from the sun of about 279 million miles, or three times farther from the sun than Earth. It is about the size of the state of Massachusetts (about 150 miles in diameter) and dense (7,000 kg/m³).

The science goals of the Psyche mission are to understand the building blocks of planet formation and to explore firsthand a wholly new and unexplored type of world. The mission team seeks to determine whether Psyche is a protoplanetary core, how old it is, whether it formed in similar ways to the Earth’s core, and what its surface is like.

If the Psyche mission is chosen for flight, the spacecraft will likely launch in 2020 and travel to the asteroid using solar-electric propulsion. After a six-year cruise, the mission plan calls for 20 months spent in orbit around the asteroid, mapping it and studying its properties.

For much of the team, this is a once in a lifetime opportunity, taking many years to plan and many more years to reach its destination. Psyche science team member Timothy McCoy, geologist and curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s meteorite collection, told the NASA panel, “I’ve been working with meteorites for 25 years, and this will be my last mission.”

Mission instrument payload

The spacecraft's instrument payload includes magnetometers, multispectral imagers, a gamma ray and neutron spectrometer, and a radio-science experiment.

The multispectral imager, which will be led by the science team at ASU, provides high-resolution images using filters to discriminate between Psyche's metallic and silicate constituents. It consists of a pair of identical cameras designed to acquire geologic, compositional and topographic data.

Psyche mission multispectral imager.

The gamma ray and neutron spectrometer will detect, measure and map Psyche's elemental composition. The instrument is mounted on a 2-meter-long boom to distance the sensors from background radiation created by energetic particles interacting with the spacecraft and to provide an unobstructed field of view. The science team for this instrument is based at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University.

The magnetometer, which is led by scientists at MIT and UCLA, is designed to detect and measure the remnant magnetic field of the asteroid. It is composed of two identical high-sensitivity magnetic field sensors located at the middle and outer end of the 2-meter boom.

The Psyche spacecraft will also use an X-band radio telecommunications system, led by scientists at MIT and JPL. This instrument will measure Psyche's gravity field and, when combined with topography derived from onboard imagery, will provide information on the interior structure of the asteroid.

The competition

The primary goal of NASA's Discovery Program is to launch numerous small missions with fast development schedules — each for a considerable cost savings compared with traditional larger missions; all while focusing on scientific investigations that complement larger planetary exploration.

In September 2015, NASA selected the Psyche mission and four other mission concepts for refinement during the next year, as a first step in choosing one or possibly two of them for development and launch. Each mission received $3 million for a one-year study.

Along with the Psyche mission, the other four Discovery semifinalists include two missions to Venus, one to the Jupiter Trojan asteroids, and a space telescope designed to look for potentially hazardous asteroids.

The Psyche mission team

“It’s unusual for people to come together from such different institutions — SSL, JPL, ASU and other universities and research organizations — and find a common culture that allows smooth communications and work. But we have done that,” Elkins-Tanton said..

“The culture we created allows anyone to speak up, and we’ve caught and solved several problems that would have gone by silently and caused trouble later, had the team members felt unable to stop the action and ask difficult questions. And we have fun together. That’s the real key.”

In addition to Elkins-Tanton, ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration scientists on the Psyche mission team include Bell (deputy principal investigator and co-investigator), Erik Asphaug (co-investigator) and David Williams (co-investigator).

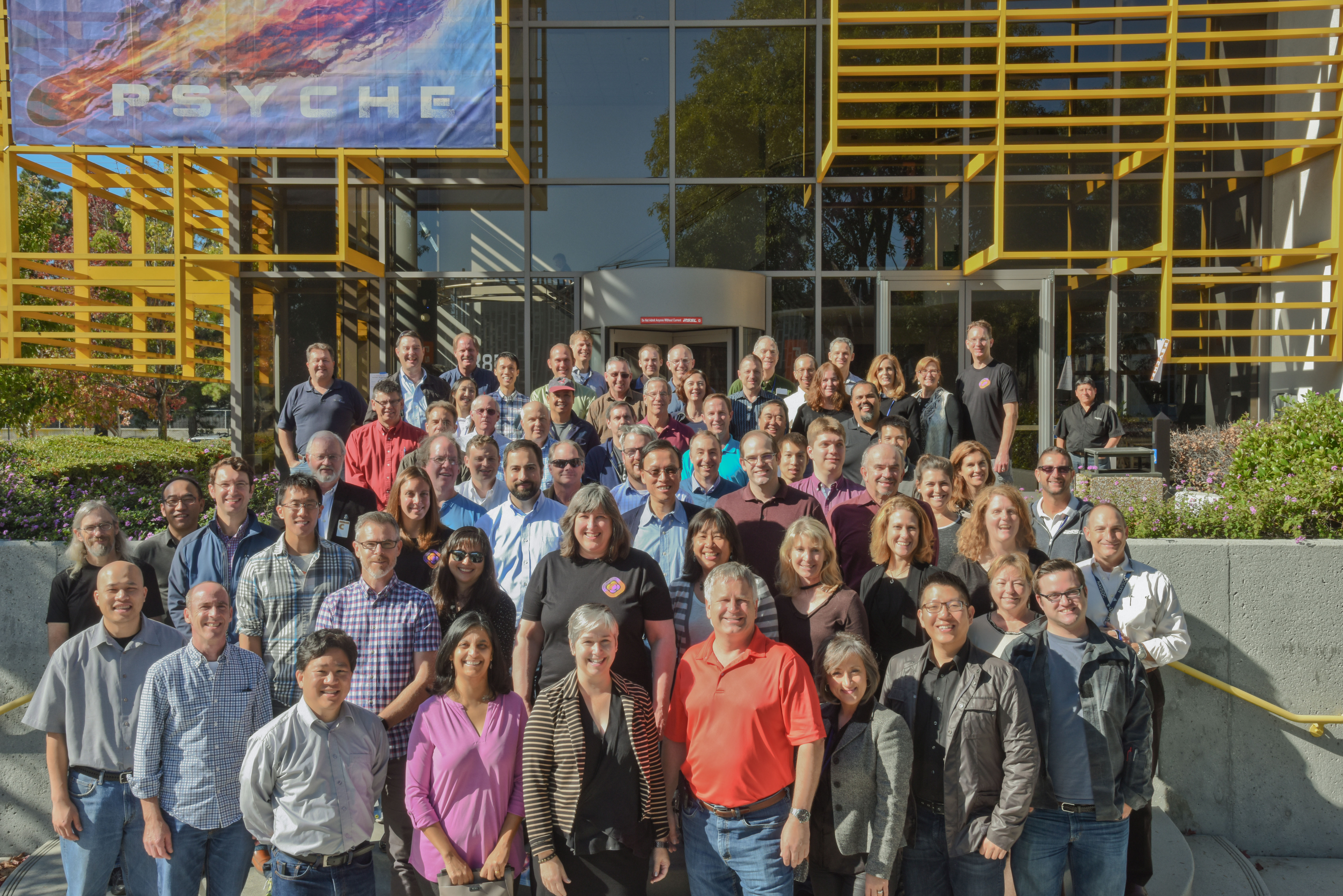

The Psyche mission team at SSL. Photo courtesy of SSL

NASA’s JPL, managed by Caltech, is the managing organization and will build the spacecraft with industry partner SSL. JPL’s contribution to the Psyche mission team includes more than 75 people, led by project manager Henry Stone, project scientist Carol Polanskey, project systems engineer David Oh and deputy project manager Bob Mase. SSL contribution to the Psyche mission team includes more than 50 people led by SEP chassis deputy program manager Peter Lord and SEP chassis program manager Steve Scott.

Other co-investigators are David Bercovici (Yale University), Bruce Bills (JPL), Richard Binzel (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), William Bottke (Southwest Research Institute, or SwRI), Ralf Jaumann (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt), Insoo Jun (JPL), David Lawrence (Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL), Simon Marchi (SwRI), Timothy McCoy (Smithsonian Institution), Ryan Park (JPL), Patrick Peplowski (APL), Thomas Prettyman, (Planetary Science Institute), Carol Raymond (JPL), Chris Russell (UCLA), Benjamin Weiss (MIT), Dan Wenkert (JPL), Mark Wieczorek (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris), and Maria Zuber (MIT).

With the site visit complete, the team then traveled to NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., earlier this month to present the Psyche mission to the head of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate and the Selection Official for the Discovery Program.

“Now,” said Elkins-Tanton, “it’s just waiting ... and keeping all fingers crossed!”

Top photo: Artist rendition of the asteroid Psyche. Image by Peter Rubin/ASU

More Science and technology

Stuck at the airport and we love it #not

Airports don’t bring out the best in people.Ten years ago, Ashwin Rajadesingan was traveling and had that thought. Today, he is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin, but back…

ASU in position to accelerate collaboration between space, semiconductor industries

More than 200 academic, business and government leaders in the space industry converged in Tempe March 19–20 for the third annual Arizona Space Summit, a statewide effort designed to elevate…

A spectacular celestial event: Nova explosion in Northern Crown constellation expected within 18 months

Within the next year to 18 months, stargazers around the world will witness a dazzling celestial event as a “new” star appears in the constellation Corona Borealis, also known as the Northern Crown.…