Palm Walk: A tale of trees, death, rebirth and mystery

A double exposure of Palm Walk in 2016 by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2016, click here.

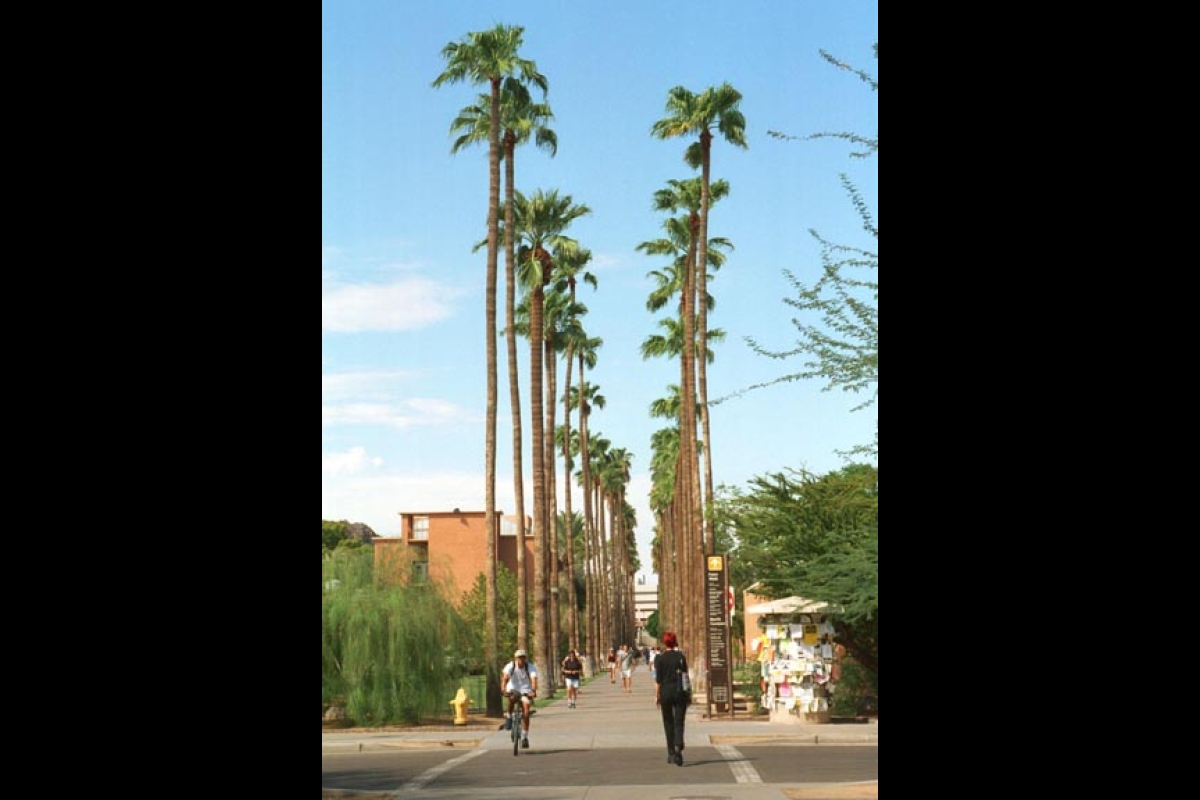

Palm Walk, that iconic image of Arizona State University, turns 100 this year.

It’s an anniversary often repeated as fact, that school President Arthur John Matthews planted the trees in 1916.

The only problem is that it can’t be confirmed.

But what can be found in the musty documents and fading photos — and the story behind it all — is far more interesting. It’s a tale of establishing an oasis in a desert, of a tiny nascent college struggling to establish itself in an infant state with a bad national image. It’s about finding balance between transformation, preservation and the inevitable.

The palms are nearing the end of their natural lifespans. They will have to be replaced.

But before we get into the specifics of the trees’ fate, let’s look at their past.

The story of Palm Walk is a tale of trees, death, rebirth, history and mystery.

The scene

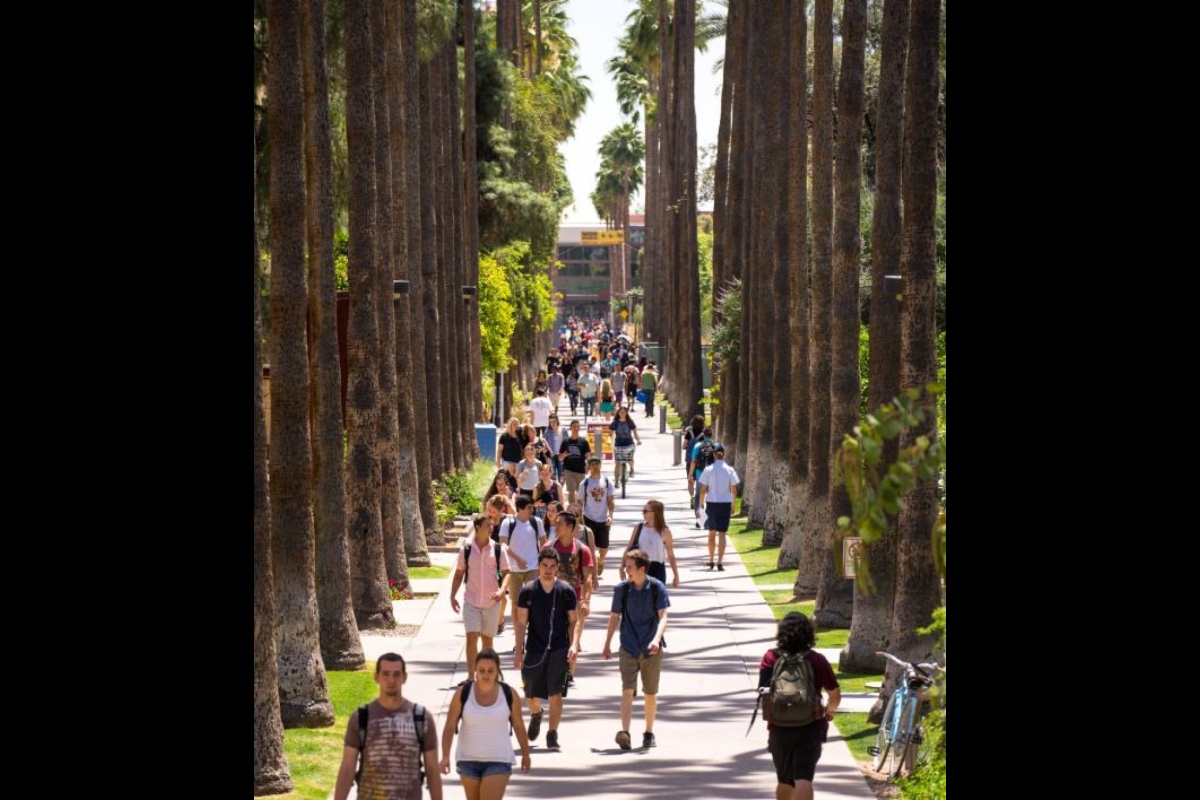

Palm Walk has been called the most photographed place on campus. The two rows of stately, elegant trees are the university’s iconic image. University landscape architect Byron Sampson calls them a "place of memory."

In 1916, the state was 4 years old and the university 31, having been established on George and Martha Wilson’s 20-acre cow pasture at a cost of $500. The only devils on campus were dust, swirling in the fields south and west of Old Main.

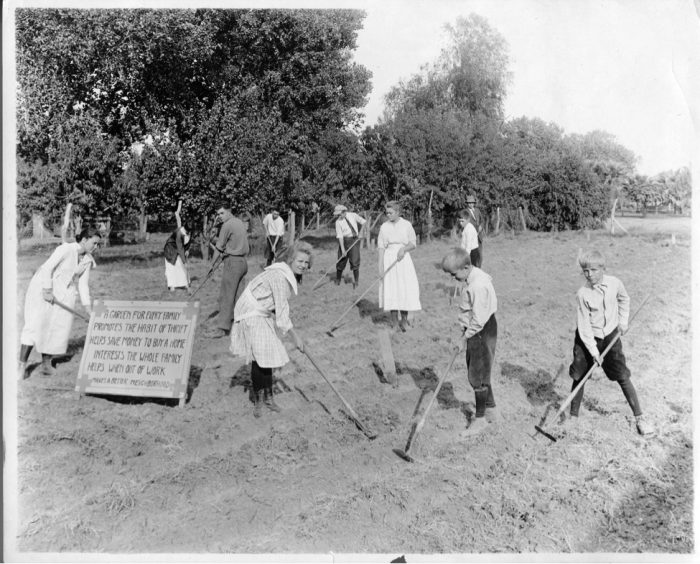

If you attended the Tempe Normal School of Arizona around 1916, you studied teaching or agriculture. Other classes were available, but those two subjects were the institution’s focus. If you studied agriculture, it meant getting out in the field — literally.

"Emphasis is placed on the practical rather than the theoretical or technical," the 1916 curriculum bulletin said. "To this end, work in the class room is supplemented by actual practice in the field and garden." One requirement of Agriculture 1: Elementary Agriculture was making your own garden.

There are only five buildings left on campus from the teens: Old Main, the University Club, the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, the Virginia G. Piper Writers House, and Matthews Hall.

What was life like for students the year the palm trees reportedly were planted? Let’s pull two names off the student rolls in 1916: Reathie Pfeifer of Phoenix and Howard Draper of Wickenburg. Both had roommates; all the dorms had were doubles. If it was hot out, they slept on sleeping porches. (The catalog goes to great lengths to describe dormitory sleeping porches. Having a sleeping porch in 1916 was like having air-conditioning in 1947. It was something you advertised that people sought out, especially Arizonans.) They paid $16.75 a month for room, board and utilities. Another dollar got their laundry done each month.

Both Reathie and Howard ate in the dining hall. The food was good. Nowadays it would be touted as artisanal, local, organic. The school had 50 acres for crops, a dairy, a hog lot and a poultry yard, all producing eggs, meat, milk and vegetables for the students.

Reathie might have belonged to the Zetetic Society, a drama club for women, or if she liked to read, the Clionian Literary Society. She might have played basketball or tennis. She had two parlors, a sitting room and a piano in her dorm. Howard’s dorm didn’t have any of that.

Howard might have belonged to the Athenian Debating Club or played football, which was in its second year at the school. School officials suspected the sport might take off. "By the interest and enthusiasm shown in this sport there is no doubt but that football will be played each year," the catalog predicted.

For entertainment that year, they could have gone to see a male quartet from Manhattan, a dramatic reader of modern plays, or the Killarney Girls and Rita Rich, "six young women musicians in Irish costumes in an evening of music and Irish humor."

Neither one of them whooped it up on Mill Avenue. "As the sale of liquors is prohibited in Arizona, the undesirable influence of the saloon is entirely eliminated," the catalog reassured parents.

The president-gardener

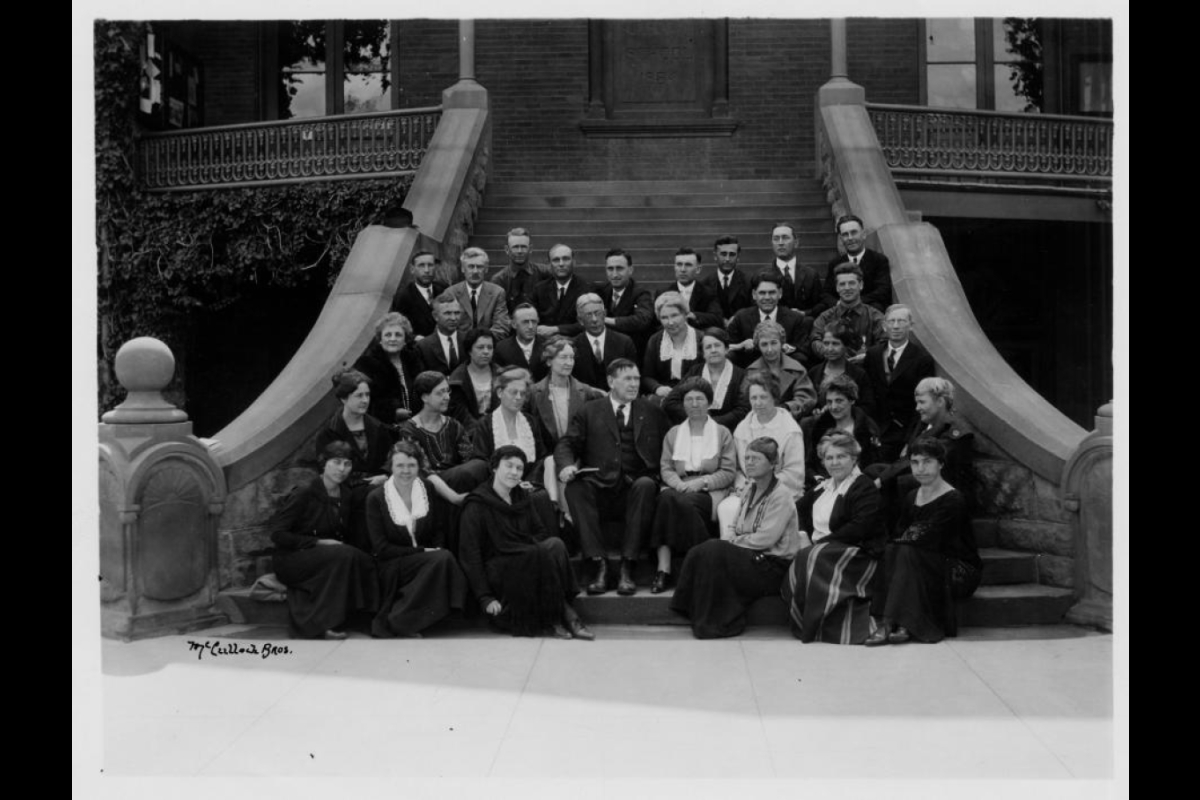

Those students were at Tempe Normal School right at the midpoint of Arthur John Matthews’ leadership tenure. He served as principal from 1900-1904 and then as the first president from 1904-1930.

Matthews has been called the "president-gardener" for his horticultural bent.

"He was very interested in beautifying the campus," university archivist Rob Spindler said.

Matthews, an Irish ex-farm boy from a small town in upstate New York, planted 1,478 trees of 57 varieties; more than a mile of hedges; and 1,512 shrubs, reportedly some of them personally.

The "Our Campus" column in the Tempe Normal Student (the State Press of the day) mentioned areas near the infirmary "lately beautified" by "good cement walks and grass" in March 1917.

Landscaping campus was far from accidental, Spindler said. In the late teens, Arizona wasn't even a decade past its status as a territory, and the rest of the country still looked at the state as a sketchy wasteland inhabited by even sketchier people. Indian fighting continued into the 1920s, and the Power brothers' shootout was two years in the future.

If Tempe Normal School was not a venerable institution, it wanted to at least look like one. Overcoming Arizona's Wild West image was the point of buildings like Old Main and the University Club (then Science Hall).

"They were designed to have ivy climbing up them like Harvard," Spindler said. "They're saying, 'Look at the Old Main fountain; we have water. It’s safe to send your kids here.' "

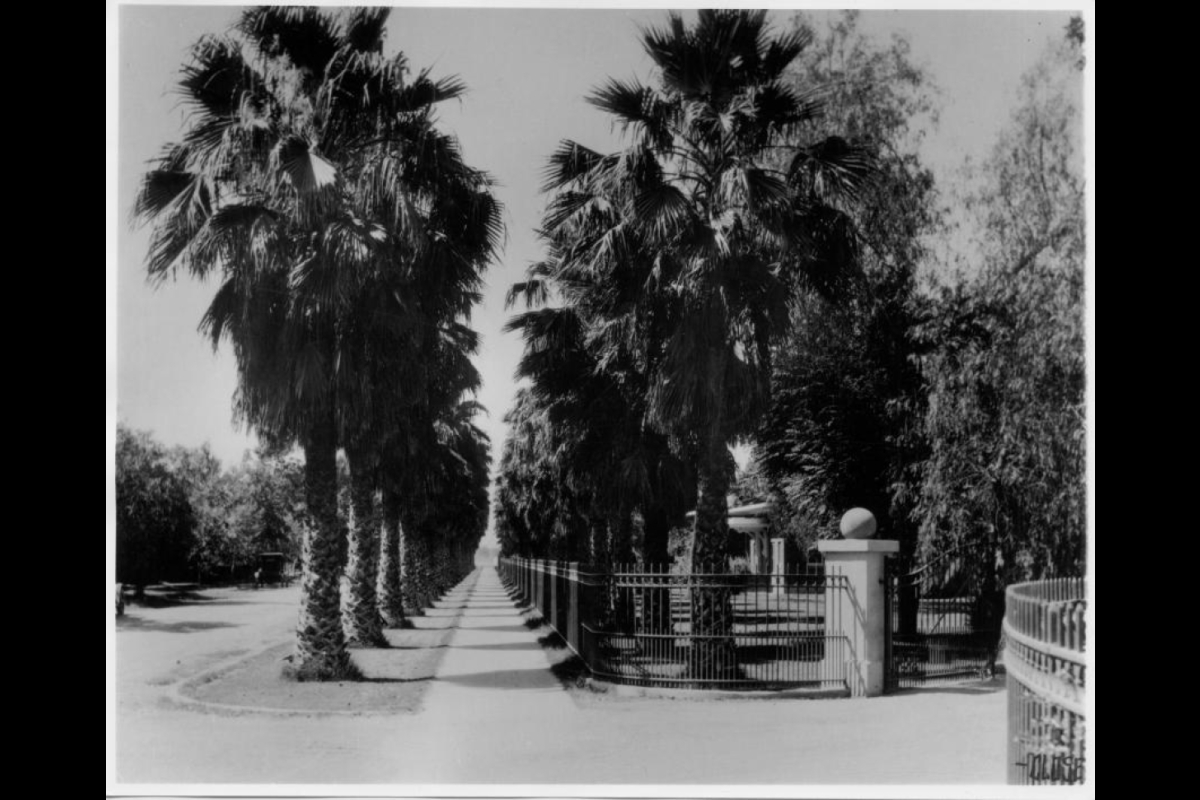

A line of tall palms would have helped convey that message.

"Matthews understood it in the teens and '20s," Spindler said.

The 1916 catalog touted a lush campus "arranged in a most attractive manner with broad, shady lawns, cement walks and graveled drives, and a profusion of trees, shrubs, and flowers."

The school didn’t have a lot of money back then, and expenditures like adding classrooms took priority.

Putting planting of the palms around 1917 through 1919 "is a reasonable estimate," Spindler said. "They were probably potted plants."

Lining Normal Avenue with palms from Eighth Street (now University) down to Tyler Mall past the infirmary (now the student health center) and the university president’s house (now the Piper Writers House) was a logical choice, Spindler said.

“It would have made sense to beautify that area,” he said. “Part of the mystery is that it was done in chunks. ... It wasn’t like we planned to have this great icon until the 1920s.”

Enrollment in 1916 was 450 students. Most of them came from Arizona, with a few from other states, Mexico and Canada. Enrollment dropped to 418 the following year, and again the next year because of World War I. Enrollment didn’t surge to 450 again until 1923.

Spindler suspects Matthews cut back on his frantic planting.

“I don’t see him spending money on trees in the war years,” he said.

Palm Walk

Calling the path Palm Walk is relatively new. In the school’s 1926 catalog it was called the College Palms. That’s the first recorded instance of it having a name.

By the 1930s “it was constantly used as an icon in the catalog,” Spindler said. The 1932 catalog called it “The Palms.”

“We were thinking of it as a signature place, as an icon for the institution,” Spindler said.

Bob Svob, university landscaper in the 1930s, kept meticulous records of every plant on campus. By 1946 there were 215 Mexican fan palms on campus, according to Svob’s typed notes.

The first mention of Palm Walk as a special place (with an accompanying photo looking pretty much like those taken today) was in a circa-1967 promotional pamphlet titled “Beautiful Environment for Higher Learning.” However, the copy referred to it in lowercase: “palm walk.”

“That’s the earliest I found,” Spindler said.

The mystery

“Here’s the problem,” Spindler said. “We don’t know when they were planted. … It’s not like there’s a memo from President Matthews saying, ‘Buy trees.’ ”

A 1919 aerial photo looking west over campus shows a line of plants where Palm Walk is now. The problem is that what species they are can’t be deciphered from the photo.

“Just little shrubs in the ground doesn’t nail it,” Spindler said.

Spindler pored through photos and handwritten financial ledgers from 1916 through 1918. Between 1916 and 1918, he found three purchases:

- March 1917: $38.45 for “trees” from H.B. Skinner.

- April 1917: $227.00 for “trees, plants, etc.” from Armstrong Nurseries.

- May 1918: $7.00 for “palm trees” from Blasingame Nurseries.

Note only one entry specifically mentions “palm trees.” That’s not enough to nail down a date.

“We don’t have a smoking gun,” Spindler said.

Death, and what’s next

The 65-foot-tall Mexican fan palms that make up Palm Walk typically have a lifespan of 100 to 110 years. One surprising fact about them: “It’s not a tree,” university landscape architect Sampson said. “It’s a tall grass.”

A sign of decline in the trees is when the crown — the knob on top, plus the fronds — begins to tilt like the head of someone dozing off in a meeting. It’s an indicator the tree has reached its maximum age. Those crowns can weigh up to 500 pounds.

Sampson is well aware that he is the caretaker of a vista that is not only iconic visually, but emotionally as well. He knows alumni will return and remember that that’s where they first saw their wife or husband.

“I’m very, very adamant about protecting them and holding them in some level of stasis,” he said. “Eventually we know we are going to have to turn to addressing this, whether we want to or not.”

The wood from the old trees won’t be repurposed. It’s fibrous and tough and notoriously hard on saw blades. It doesn’t even burn well.

“The trunk has been used in many cultures for sculpture or a variety of things, but we have no plans as such,” Sampson said.

They will be replaced with date palms, which will provide two things the Mexican fan palms do not: shade and dates. The dates will be harvested, sold and eaten. The solution speaks to two of the university’s enduring institutional objectives: sustainability and leveraging place.

“It’s not something that’s just pretty,” Sampson said. “It’s something we engage with. … We bring about the physical manifestation of the New American University. How do we do it?”

The replacement trees will be about 18 to 20 feet high. It’s the maximum height that can be planted without using a crane. A utility tunnel runs underneath all of Palm Walk, so a crane can’t be maneuvered in there. When the new trees are mature, they will be about 80 feet high.

Planning the replacement operation will be complete by the end of the first quarter of the year. Beyond that, a timeline hasn’t yet been established.

“There is a desired plan of action, and as with anything there is the reality,” Sampson said.

Aside from the logistics of replacing 110 trees in the heart of a campus as perpetually busy as Grand Central Station, it’s not as simple as running down to the nursery. Because they will be mature date palms, they will likely belong to growers, who will expect a good price for a productive tree. Sampson and the landscape contractor will have to visit growers and nurseries as far away as Southern California to find 18-foot trees with clear straight trunks. “I want the crowns to match,” Sampson said. “I want the heads to match.”

As it has been since 1916, the university will continue to remain, in Sampson’s words, “an oasis of education in a hostile environment.”

“Craft a vehicle and protect the sites of memory?” he said. “It’s always a continuum.”

And there will always be palms on Palm Walk.

“Always, always, always,” Sampson said.

More Sun Devil community

New ASU women's basketball coach has sights set on championships

Molly Miller apologized for being a few minutes late for her Zoom interview Sunday afternoon.No apology was necessary.It’s been a crazy and hectic 72 hours for Miller, who guided Grand Canyon…

SolarSPELL wins 'best in show' award at South by Southwest

Arizona State University professors from a variety of disciplines made a big splash at the South by Southwest festival of technology and culture in Texas earlier this month.The ASU SolarSPELL…

How 2 women who call each other 'sis' raised ASU running back Kyson Brown

The Lancaster High School graduation ceremony has just ended, and running back Kyson Brown poses for a photo with the two most important people in his life. ASU…