Ever have one of those (usually late-night) conversations about whether a grizzly bear could beat a great white shark in a fight? Or a lion vs. a gorilla?

Combine that with a sports bracket and you have (wait for it) March Mammal Madness, where the claws come out and the fur flies in imaginary matchups between more than 60 species.

Now in its fourth year, the event is managed by a team of evolutionary biologists who pick a different bunch of animals each year and then imagine who would win based on science. And it inspires a surprisingly fervid response from a general public not known to get passionate about science.

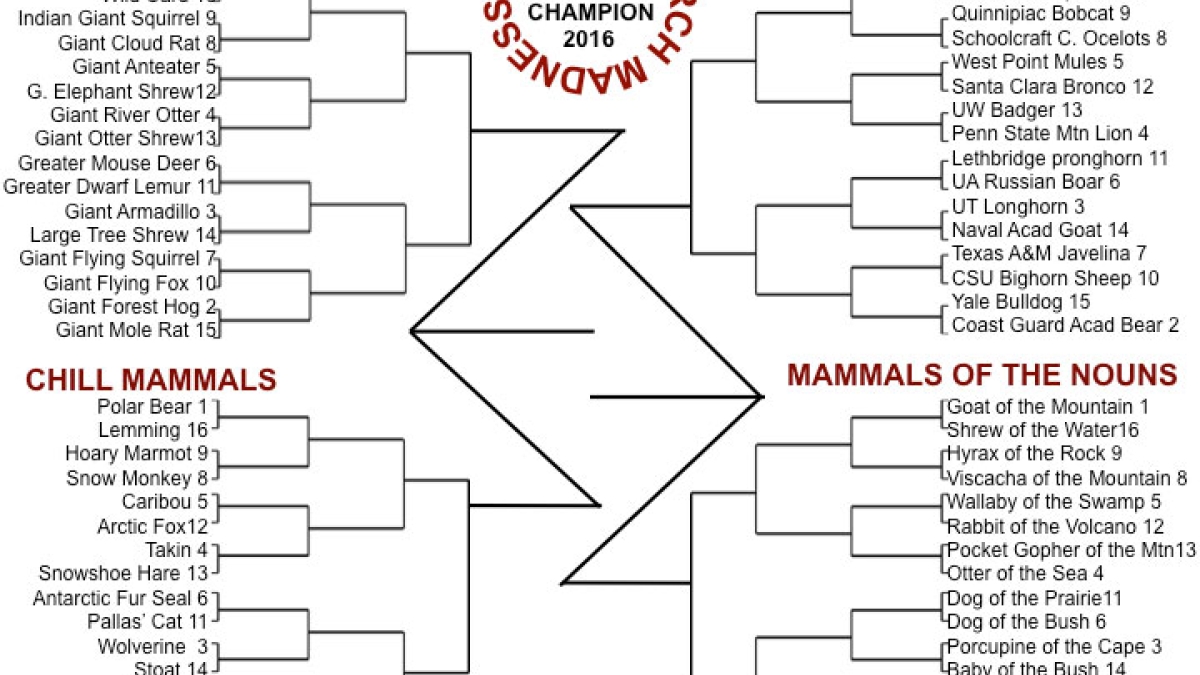

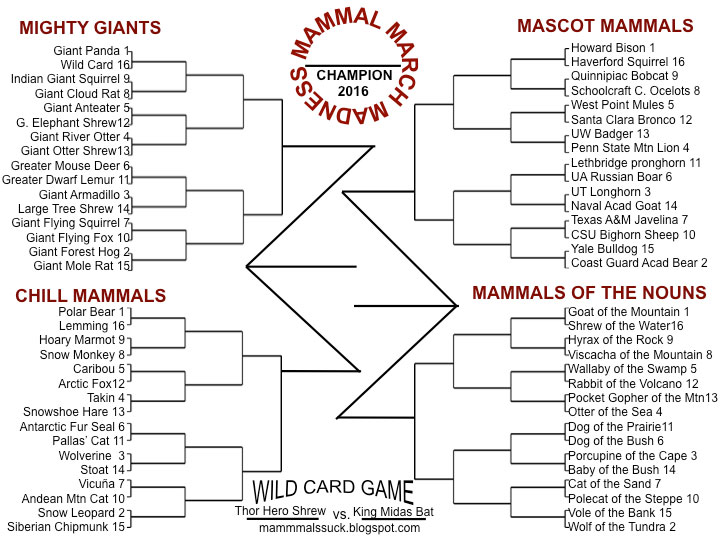

This year pits the giant forest hog vs. the giant mole rat, the Pallas cat vs. the Antarctic fur seal, and the badger vs. the mountain lion, among many other contests. May the best critter win.

Don’t expect them to shake out the way you suspect. Winners are based on science, said Katie Hinde, associate professor at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change The School of Human Evolution and Social Change is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (CLAS). The Center for Evolution and Medicine is a a CLAS research unit and member of the Biodesign Institute.and the Center for Evolution and Medicine, one of the four organizers of the event.

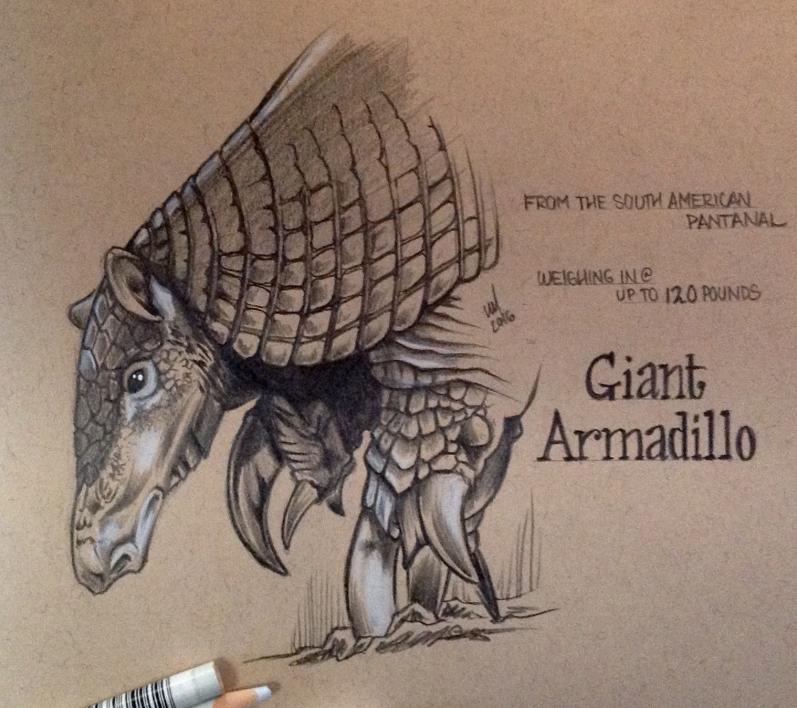

The 2016 March Mammal Madness features animals in four brackets: Might Giants, Chill Mammals, Mascot Mammals (such as this Schoolcraft College Ocelot) and Mammals of the Nouns. All illustrations by Charon Henning

A couple of years ago they had a division based on animals not many people have heard of — such as the binturong, a big tree weasel.

“It was our Cinderella that year,” Hinde said. The binturong was not predicted to win a lot of battles. “It ended up having to fight a dhole, which is a large dog species. It was like, ‘There is no way a binturong can fight and win against a dhole.’ ”

But, the day before the match, the dhole had won, and was presumably full of whatever it killed. Hinde did research on the gut passage time for different wild dog species.

“Is the dhole full and still digesting from the day before, and therefore not motivated to fight? You see that in the wild all the time — gazelles walking past lions with distended bellies who have no interest in hunting.”

Real-world factors like biology, physiology, metabolism, illness and injury are all taken into account.

“A lot of laypeople think of science as dry and dusty and memorization of a lot of facts,” Hinde said. “What it really is is one of the most creative things you can do. You have to think and imagine things about the world in order to design the studies we do. This is an opportunity for us to celebrate the imagination of science.”

Hinde and her three colleagues keep an idea file they contribute to all year long.

“When we read exciting science or encounter cool research or when we see something that just looks really interesting, we put it in the file,” she said.

In the fall, the quartet looks for clear divisions among the mammals to showcase different aspects of natural history and to keep the contest new and fresh. This year, one of the divisions is Chill Mammals — species which live in cold places or at high elevations.

After the animals are selected, Hinde and her colleagues spend weeks researching them to determine who will win. They divvy up the battles and find justification for the outcomes in the scientific literature.

“I basically have a month of biology boot camp, where I’m reading all the science and thinking of science differently than I do when I’m working on my topic, but I also get to see so many peoples’ joy and awe in learning about the natural world,” she said. “We reach a consensus on the probability of what the outcome will be. Sometimes it’s a 98 percent chance and sometimes it’s a 1 percent chance. In the wild, the lion doesn’t always get the antelope. Things that are unexpected can happen.”

At points like that, the team fires up a random number generator.

“That’s when things get very interesting,” Hinde said. “We do all that before the bracket is published.”

In the early rounds, the better-ranked species have home-court advantage. They talk about how the two combatants will fare in that environment. For example, last year there was a division called Mythical Mammals. The top-ranked unicorn faced off against the winged horse Pegasus. According to medieval literature, unicorns lived in dense forests. Because Pegasus couldn’t use its wings in a thick wood, it lost.

“These are the things we get people to think about, but these are the things we think about as evolutionary biologists,” Hinde said. “We think not only ‘What is that animal like?’ but also ‘What is that animal like in relation to other animals in its environment?’”

That was the key behind a huge upset last year. A photo snapped in England of a least weasel riding a flying woodpecker went viral.

“We already had a bracket, and we had the least weasel in it,” Hinde said. “What was amazing was all these people picked the least weasel, without doing any research on it! ‘That thing is so (tough) it rides birds!’ They loved it. This is our winner. It lost in the first round. People were so enamored with it that they didn’t do research on the tenrec that it had to go up against.”

The tenrec is a tiny mammal that looks like a hedgehog on crack. It lives on Madagascar and has spines that can rotate 180 degrees. The least weasel’s kill strike goes for the nape of the neck.

“For the tenrec, that’s where its biggest … spikes are,” Hinde said. “If they were to encounter each other and the least weasel was audacious enough to take on the tenrec, its fight style would put it at a huge disadvantage. It ended up losing. That’s when people started putting on their brackets ‘Tenwrecked.’ ”

The first year about 20,000 people visited Hinde’s blog page, which hosts the event. Last year that number ballooned to 180,000. Museums and biology organizations tweet pictures of the animals during the contest. Tattoo artists contacted Hinde and offered to draw pictures of all the animals.

“People get into this,” Hinde said.

Last year she took a call from an extremely enthusiastic man.

“ ‘I’m playing Mammal March Madness with all my buddies, and we’re meeting tonight at the bar, and I have to give them updates but I’m having a hard time finding out what happened last night. Could you tell me what’s going on?’ ... He said he never expected he’d be interested in biology and learning about all these animals, but it was really, really fun, and he and his buddies were having a great time.”

March Mammal Madness doesn’t only appeal to men in bars with time on their hands. Hinde has heard from high school students who started out following the contest as a biology assignment and became emotionally attached to the animals. Teachers love it.

“If you’re a teacher and you tell a roomful of teenagers they have to research 65 animal species, can you imagine the bellyaching?” she said. “But if you hand them a bracket of 65 animals and tell them it’s a tournament and there will be a prize for the student with the best score, all of a sudden you’ve created this incredible motivation for individuals to go and read about those animals, find out how they fight, find out how they have claws or armor or teeth, or what environment they live in, to anticipate how an outcome would be if they encountered each other in the wild.”

Get your bracket and follow the play-by-play at mammalssuck.blogspot.com. Bracket courtesy of Katie Hinde

Play-by-play and bout results are announced on Twitter, all the way down to the Final Roar. Outcomes are posted on Hinde’s blog at http://mammalssuck.blogspot.com/

After today, participants will have 6 days to research the animals and fill out their bracket before the wild-card round between Thor’s hero shrew and King Midas Bat launches the tournament on March 7.

People have two options to follow the action:

1) Follow the hashtag #2016mmm on Twitter. This is where all the trash talk happens.

2) For teachers and parents who don’t want to hear how the greater dwarf lemur is absolutely going to crush the greater mouse deer and just want the science and rankings, go to https://twitter.com/2016mmmletsgo

More Science and technology

The Sun Devil who revolutionized kitty litter

If you have a cat, there’s a good chance you’re benefiting from the work of an Arizona State University alumna. In honor of Women's History Month, we're sharing her story.A pioneering chemist…

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…