Trying to solve the many problems of the world can seem overwhelming, but three Arizona State University teams are showing that social progress and business can go hand in hand.

The three ASU groups are pursuing social entrepreneurship, which uses a business model to improve lives. Success requires a firm familiarity with complex, often intractable problems, and the ability to make enough money for the enterprise to be sustainable.

One of the teams, the All Walks Project, won the $20,000 grand prize in the Pakis Social Challenge entrepreneurship contest on Feb. 4, but in a surprise move, the judges awarded money to the other two teams as well. Humanity X and 33 Buckets both received $10,000. The Pakis Family Foundation, which funded the prize, essentially doubled the money it intended to invest in the ASU teams. All three teams also will receive mentoring and acceptance into the Seed SpotSeed Spot is a Phoenix-based incubator that provides space and assistance to entrepreneurs. business incubator.

Each team had already won $7,500 as a finalist, and their members include young people who are passionate about finding innovative ways to tackle crises that affect thousands of people.

Here is a look at the three finalist teams for the Pakis Social Challenge:

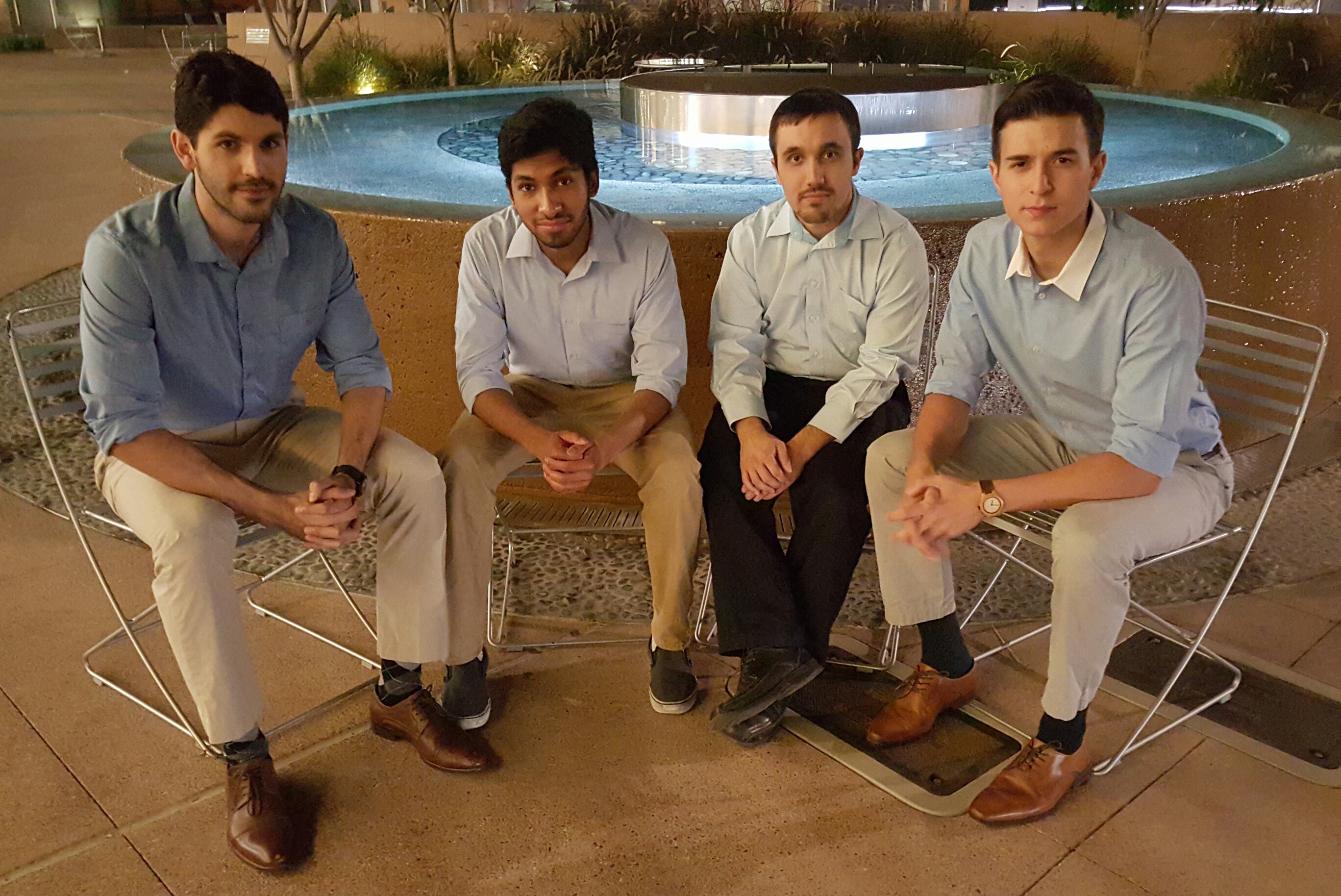

The 33 Buckets team, from left: Mark Huerta, Swaroon Sridhar, Paul Strong and Vid Micevic.

33 Buckets

The team: Paul Strong, who has his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering and works at Honeywell; Mark Huerta, who has his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biomedical engineering and works at Arizona Engineering Technologies; Vid Micevic, an undergraduate sustainable engineering major, and Swaroon Sridhar, an undergraduate biomedical engineering major.

The concept: The team installs water-filtration devices in developing countries and trains the communities to maintain the equipment and sell the clean water.

Why it’s unique: The filtration device, which fits inside a small shed, is modular, and parts can be easily replaced. The clean water produced becomes a small business, which provides incentive for the community to maintain the device. A major component is education for the community about the importance of clean water. “They need to know the reason we’re doing it or they won’t embrace it,” Huerta said.

The business model: The team levies a small tax to pay for the upfront costs of installing the equipment plus maintenance and salaries for the local people in charge of distribution, and government organizations devoted to clean-water initiatives pay the costs of the team.

“We work with the leadership of the community to come up with a fair financial model that will ensure the sustainability of the filtration system,” Huerta said. “In Peru, a family typically pays $12 a month to buy clean water. When you’re only making $50 a month, that’s a substantial amount. So most of the people don’t buy clean water. The tax will be anywhere from $2 or $3 per family per month.”

Background: The project was launched in 2010 as part of the Engineering Projects in Community Service Program, or EPICS, in ASU's Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. Strong and four other students worked with mentor Enamul HoqueHoque is an ASU alumna who endowed the E.M. Hoque Geotechnical Engineering Laboratory at the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment at ASU., who is from in Bangladesh. Hoque’s brother is principal of a girls’ school there, and the ASU students decided to install a filtration device at the school because they knew the water in Bangladesh was tainted by naturally occurring arsenic.

However, in 2012, when the team got to the school and tested the water, they found that it contained no arsenic, although it did contain bacteria. “We had to start over,” Strong said. “We changed a lot of what we were about. We went away from the design side and more toward the sustainability side of the project.”

The team knew that frequently, outsiders will come in and build water filters in poor villages and then leave. Soon, the devices break and become useless because there is no incentive for the community to maintain them. So they created a profit model. The team crowdfunded $10,000 and returned to the girls’ school in December 2014 to install the water filter and train the local people. The students take the clean water home in containers, and the school sells water to local vendors and tea shop owners, making money it can then spend on education and to maintain the filter.

Now the team is working on two new projects; in the Dominican Republic, where village children have to crawl into a cave with buckets to fetch water, and in a village in Peru, where the water contains harmful bacteria.

Why it’s important: Contaminated water can transmit diseases such diarrhea, cholera, dysentery, typhoid and polio and is estimated to cause 502,000 diarrheal deathsAccording to the World Health Organization. worldwide each year, most of them children under age 5. “Education is not only the way to get people to understand (what we do), it’s also the way to get people to escape poverty. And that’s our overarching goal,” Sridhar said.

The All Walks Project team members, from left: Erin Schulte, Jasmine Anglen, Brittney McCormick, Brittany Ater and Jessica Hocken.

The All Walks Project

The team: All the members are ASU undergraduates. The co-founders and their majors are: Jasmine Anglen, finance and management; Erin Schulte, global studies, and Jessica Hocken, accountancy. Brittney McCormick, director of strategic outreach, is a biology major, and Brittany Ater, director of customer relationships, is a psychology major.

The concept: The All Walks Project created a training curriculum for volunteers to provide life skills to survivors of sex trafficking. The goal is for the victims to rehabilitate their lives and avoid being drawn back into a life of abuse. All Walks also created a kit for colleges to launch their own All Walk Project chapters to increase awareness.

Why it’s unique: Attention has increased on sex trafficking and the idea of treating the girls and women who are trafficked as victims who are coerced into sex acts and not as criminals. However, little has been done for the survivors once they are in shelters, and the relapse rate is high. The All Walks Project addresses that aspect of recovery. “Our goal is to provide very trauma-informed, specialized care,” Anglen said.

The business model: Most survivors of sex trafficking live in domestic-violence shelters after they are extracted. Providing the All Walks courses to survivors will make the shelters eligible for grants. All Walks will then take a fee from the shelters that receive grants.

Background: A few years ago, Anglen was very moved after hearing a woman speak about being a survivor of sex trafficking. A finance major, Anglen had been working toward a career as an investment banker when she visited Wall Street with other students. She realized that investment banking was not for her and decided to launch an entrepreneurship project to solve the crisis that was keeping her awake at night.

The plan won the Social Venture Partners Rapid Pitch Competition with All Walks and, a few months later, Anglen attended the Clinton Global Initiative University.

“Within a couple of months I was in over my head, and that’s when I found my co-founders,” Anglen said.

Anglen, Schulte and Hocken then delved into the research and developed a business plan, which was accepted by the Edson Student Entrepreneur Initiative, which provides funding, mentorship, space to work and technical support. Soon, the team was collaborating with the McCain Institute on several events, including Sex Trafficking Awareness Week in January.

The project now has a financial literacy course for survivors and is working on a GED course. “In other parts of the business, we adhere to try, fail and try again, but in our curriculum, it’s as expert-based as possible so it’s effective from the get-go,” Anglen said.

The women are especially proud that All Walks chapters will be started at Grand Canyon University, the University of Arizona and Northern Arizona University this year.

The horrific subject matter sometimes makes the work difficult, but Anglen said the team members take comfort in the importance of their mission. “It’s difficult because people don’t want to talk about this,” she said. “I’ve been told in fast-pitch competitions that I need to not dwell on how dark and terrifying it is. I’ve had people tell me it’s never going to change.

“I don’t believe that.”

Why it’s important: There are no official statistics, but the Polaris Project estimates that 100,000 children are victimized in the sex trade each year. Most are first trafficked between ages 12 and 14, sometimes by a male who pretends to be a “boyfriend.” “A lot of survivors don’t understand that they have been trafficked,” Anglen said. “They’ve been treated as a criminals. There’s no such thing as a child prostitute.”

The Humanity X team members, from left: Kacie McCollum, Bin Hong Lee, Jordan Bates, Ram Polur and Pat Pataranutaporn.

Humanity X

The team: Jordan Bates, a doctoral student in applied mathematics for the life and social sciences at ASU, is president and CEO; Pat Pataranutaporn, an undergraduate biological sciences major, is director of creative strategy and innovation design; Kacie McCollum, who is on the faculty at the University of Phoenix, is director of operations; Ram Polur works full time as director of clinical informatics; and Bin Hong Lee, an undergraduate software engineering major, is director of product development and outreach.

The concept: The Humanity X team has created ArkHumanity, software that scans Twitter and can detect tweets posted by people who might be suicidal. The tool picks up specific keywords that are used by people who are in crisis. ArkHumanity has an algorithm that uses context to skip false positive tweets, such as “I’ll kill myself if the Cardinals don’t win,” from authentic sentiments.

Why it’s unique: Most interventions rely on people in crisis calling a hotline number or otherwise reaching out. This model will allow behavioral-health providers to be proactive in finding people who might be contemplating suicide by spotting their warning language in real time.

The business model: ArkHumanity, when perfected, can be sold as a service to professional behavioral-health providers such as hospitals or crisis centers.

Background: The team came together through serendipity, meeting at the Hacks4Humanities Hackathon in fall 2014. Bates had been a “Data Science for Social Good” Fellow at the University of Chicago in 2013 and became familiar with the city health department’s application that tracked cases of food poisoning by finding key words on Twitter. Both Bates and McCollum had lost friends to suicide and knew that crisis intervention was an area that could benefit from that type of emerging technology.

The team won the Hackathon with their ArkHumanity prototype. At Changemaker Central on the ASU Tempe campus, they found space to meet as well as inspiration. In spring 2015, the team won the Changemaker Challenge contest, which came with $10,000 in funding.

Humanity X used the money for technology development and consultation with experts in the field, including the Phoenix-based Teen Lifeline. If the team wins the Pakis competition, the money will go toward efficacy testing and further development.

The team is also working on other projects, including one that uses virtual-reality experiences to promote social justice.

“If we can match humanity with emerging technologies, we can create something meaningful,” Pataranutaporn said.

Why it’s important: Suicide is the 10th leading cause of deathStatistics are from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. in the United States. In Arizona, almost three times as many people die by suicide than by homicide and it’s the second leading cause of death for ages 15 to 34.

More Business and entrepreneurship

ASU Prep program turns students into statisticians through the power of sports

Ask a high school kid if they want to attend a statistics class, and they might give you a blank stare or just laugh.Ask them if they want to go to a professional baseball game and their response…

The business behind the brand

Ask Jennifer Boonlorn ('01 BS in marketing) about the secret to a successful career in the luxury fashion industry and she'll tell you that community building is top of the list."I want to share…

Thunderbird at ASU ranked No. 1 in QS International Trade Rankings for third consecutive year

For the third consecutive year, Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University has been recognized as the world leader in international trade, a distinction awarded by…