Seeing a lab filled with researchers peering through microscopes, examining petri dish contents or adjusting controls on incubators isn’t a rare sight at Arizona State University. But in ASU’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts?

It’s becoming a more common scene with the prominence of SANDS (Social and Digital Systems), Stacey Kuznetsov’s research lab, which houses the tangible intersection of arts and sciences.

Kuznetsov (pictured left), an assistant professor of human computer interaction in the ASU School of Arts, Media and EngineeringThe School of Arts, Media and Engineering is a collaborative initiative between the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering., is affiliated with the School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering. A part of a growing sector of researchers merging creative pursuits, technology and science, she’s also among the “first wave” of scholars engaging in the emerging academic field of Do-It-Yourself Biology (DIYbio), or “amateur science practice.” Kuznetsov and her team of student researchers in the Herberger Institute examine ways to create low-cost tools for “citizen science.”

“We’re looking at ways to visualize different biology techniques for beginners, or to let people collect and share the data,” Kuznetsov said. “For instance, if they’re working on a project in their maker-space or garage, how can they capture the information that they’re producing and share that with the broader community?”

Another fascinating question Kuznetsov explores is how to take that knowledge and make it applicable, lacking the specialized space of a traditional lab equipped with its traditional tools.

“Recent open-source bio tools enable biology work outside of professional settings for a fraction of the cost, and I see these as parallel to the more widely studied DIY platforms such as Arduino, Raspberry Pi, PICAXE, to name a few,” Kuznetsov said, referencing software programs commonly used by artists. She first became involved with such systems when she interned at the Microsoft Research Lab at Cambridge and conducted extensive research on DIYbio initiatives around the world.

Kuznetsov finds that the DIYbio movement aims to make science more accessible, and she recognizes the discipline of biology as a platform for a new frontier, similar to where electronics, software and hardware development stood not too long ago.

“I feel like biology is doing that for us now as more tools are becoming open-source,” she said. “That’s where the future seems to be going. We’re developing basic tools that non-experts can use to do biology outside of professional labs.”

By “we,” Kuznetsov means herself and her student researchers, as well as the broader DIYbio community at large. And by “basic tools,” she’s referring to instruments “like microscopes and petri dishes that are already available at a pretty low cost. There are a lot of fun hacks you can do … for instance, you can actually turn your phone into a microscope for something like $5 by flipping the lens for the camera.”

“All of this is exciting, because the groundwork is already there,” she said. “But what’s missing, in my opinion, are easy ways to get the information we need to get started. There are a lot of online resources, but there aren’t many tools that are embedded, like maker-space, I think that people can use.”

Another thing Kuznetsov finds is that people are more receptive to hands-on work.

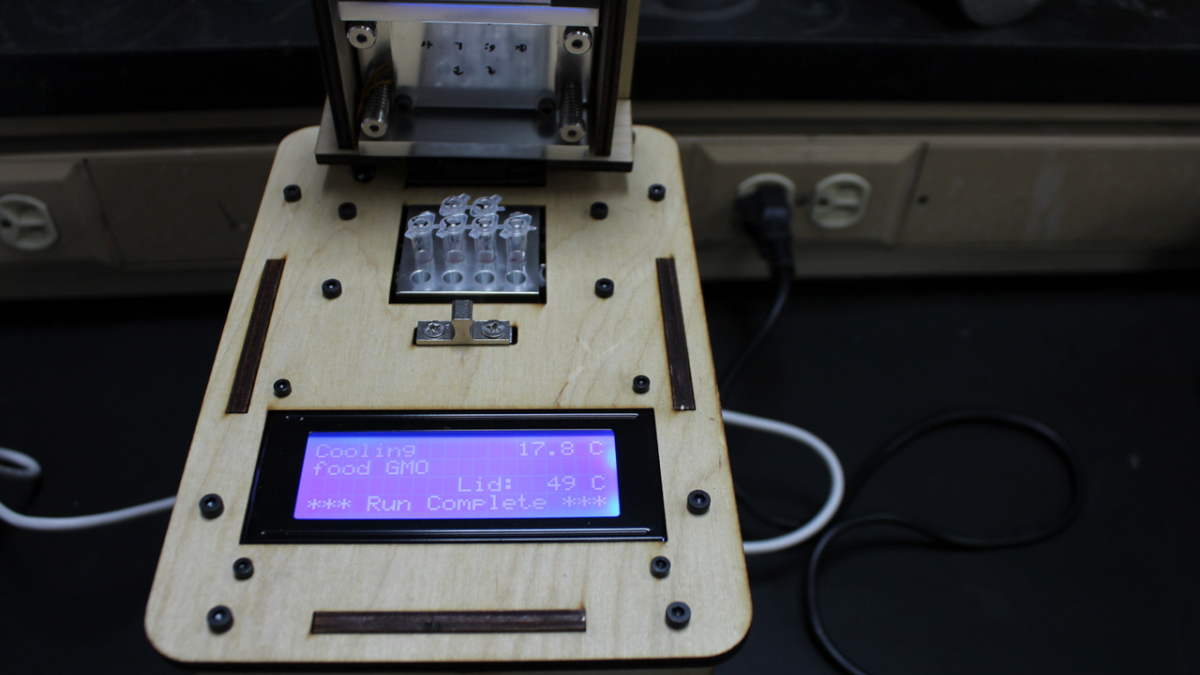

“Problem-solving is creative,” she said, “so when you’re trying to make biology happen, you have to get creative. For instance, we don’t have an incubator, so we’re making like an incubator from scratch. It’s discovering methods that fit into our lab and making a process that works in the space that we have.”

In other words, necessity inspires creativity.

“On the interaction science side of it,” she continued, “the tools we end up developing for beginners will necessarily be creative to help people learn how to do this kind of work.”

Kuznetsov also makes it clear that the science side of the equation doesn’t define the relationship between art and biology.

“I think there are also ‘bio-artists’… people who create art with biology,” she said. “For instance, people will make patterns out of cells that have an aesthetic to it, or they’ll sonify the progress of different biological processes. I think there’s a lot of room where people can actually apply art to biology and still learn the biology behind it, but then turn that into a creative project. Not all of the outcomes have to be ‘citizen science’ outcomes. Some of them can be creative practice outcomes.”

Written by Kristi Garboushian, School of Arts, Media + Engineering

480-727-1161, kristi.garboushian@asu.edu

More Science and technology

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…