Hair and the 'n-word': Connecting with Neal A. Lester

From novels and plays to personal ads, dolls and Disney movies – it’s all fair game for literary analysis as far as Neal A. Lester is concerned.

“I can look at anything as a text,” says Lester, associate vice president for humanities and arts, and professor of English at Arizona State University. “I’ve always tried to look at what seems to be insignificant, to raise that to this other level of significance. Texts don’t create themselves in a vacuum. They come from some sort of cultural context.”

Lester directs Project Humanities, a university initiative that seeks to make humanities at ASU more robust through research and public programs. Some of the project’s past programs include a conversation on Truth and the Arts featuring acclaimed choreographer Bill T. Jones, and a celebration of American music with performances and discussions of jazz, rock, gospel, barbershop, Native American music and more.

Lester joined Research Matters writer Diane Boudreau to discuss what humanities are, why and how they are important, and where his own research has led him.

What do the humanities encompass? What does it mean when you talk about “doing humanities?”

As humanists, we analyze texts, we look at things, we raise questions. The thing that can frustrate people about humanities is that we are trained to pose a series of questions and a series of multiple answers. How do you make moral decisions? How do you arrive at truth? How do you resolve conflict?

It’s always about people. It’s about people as whole. It’s about more than one person coming together. We’re doing humanities when we have a connection on some significant level.

What I like to talk about is “everyday humanities.” I like to observe and make people aware of the kinds of questions and the things we do that become so everyday that they become invisible.

Can you give an example of this?

One thing I study is the race and gender politics of hair. What happens in conversations about hair is that telling my story inherently connects to somebody else’s story. We may not have the same story, but we all have a story to tell.

When I taught a class on hair, I had students make a collage of their hair stories, and the things that they came up with were always things that connected them to parents, or friends, or neighbors, or barbershops or boyfriends.

There was one student who said that in her relationship with her boyfriend, every time she became angry with him, she would cut her hair. Her hair represented her power and she knew that he liked her long hair.

All this effort to comb hair, to tease hair, becomes a social construction of something. We are constructing meaning in that. That to me becomes an embodiment of humanities, because we’re all trying to make meaning of something.

So what is your hair story?

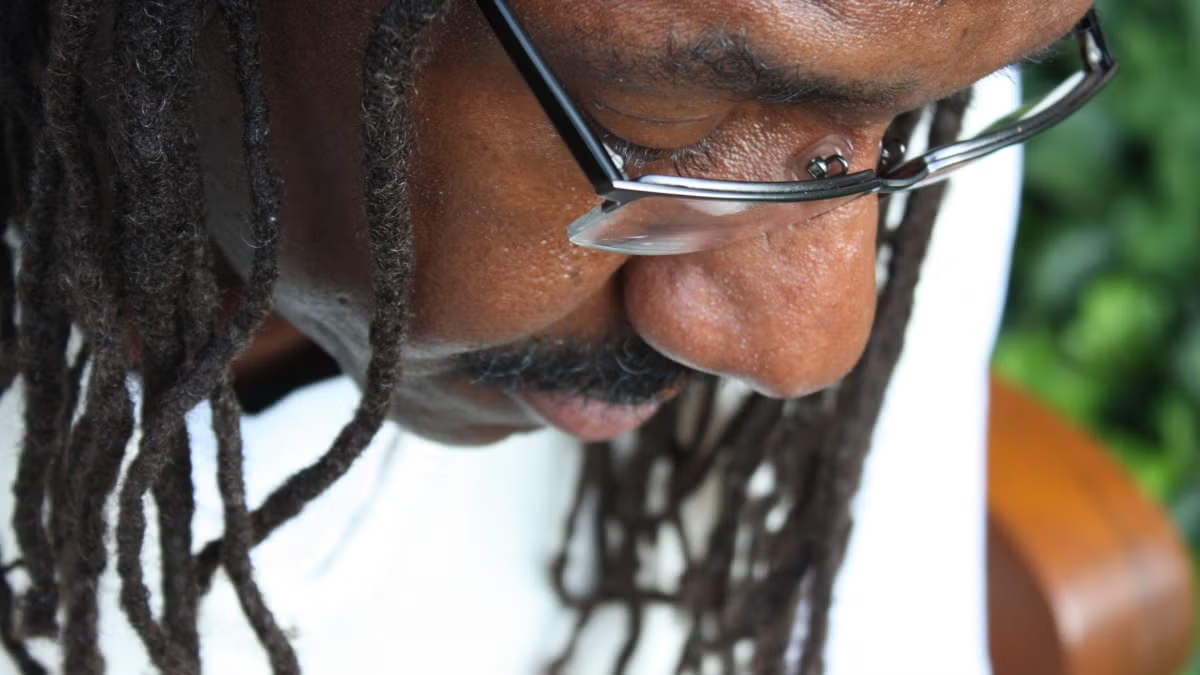

I started growing dreadlocks when I decided to leave the University of Alabama, just before coming to ASU in 1997. It was a way of claiming a part of me that I felt was being taken because of a situation I was going through. So it was a spiritual reclamation of sorts. I was concerned about that, because I’d always been conservative in my hairstyle and in my dress. Conservative equaled “professional.” So for me to have dreadlocks – that was always for somebody else, it wasn’t for me.

It’s been interesting because I’ve been able to learn about other people as well as myself through my hair. I’ve had responses ranging from “Oh you must be a musician,” or “I can tell you’re not in corporate America.” Or, everybody insists that I’m the black male they know with dreadlocks. So if they’ve ever known a black male with dreadlocks, I must be that person. We must all look alike – black males with dreadlocks!

Why is it important to study hair?

I’ve been contacted by attorneys before about a case where someone was discriminated against based on hair. A parent contacted me because her son was not being allowed to play on a basketball team because of his hair. So this research is not disconnected from everyday experiences.

An interesting thing related to hair and its relevance came last year when there was a rash of hair thieving across the country. The New York Times and Channel 12 approached me for interviews. But each person who approached me did so with suspicion, as though it was funny that people were stealing hair.

What I tried to say is that hair is extremely important in folks’ lives. In these economic times people are trying to be entrepreneurial. It was actually quite clever – you can steal this hair, it has no barcodes on it to trace origins, and you can sell it out of the trunk of your car. And it’s sustainable, because if you wear hair extensions, you have to have it done again every few months, and get new ones ‘installed.' They damage your hair if left in too long.

It’s not odd that people would steal hair. What’s insane is that folks are still so wed to this notion that there’s “good hair” and “bad hair” that these standards of beauty will drive people to all kinds of ends.

Tell us about your research on personal ads.

I was curious about personal ads because I teach courses on biography and autobiography. To me, personal ads were just abbreviated versions of autobiographies and biographies. You choose what you want to write about yourself and another person based on some activity or desire, but you do it in this really succinct and abbreviated way.

The existing literature on personal ads looks at sexuality and gender, and even class, but people had stayed away from race. So I came up with this idea that I would see how we can read race in these ads. The research led to a book, Racialized Politics of Desire in Personal Ads (Lexington Books, 2007), co-edited with Maureen Daly Goggin, a rhetorician and material culturalist, and now the chair of English at ASU.

What is interesting about personal ads is that they illustrate this difference between the public and the private. We can be very polite and politically correct in our everyday lives but in these private spaces of our imaginations, some of the most racist, sexist and homophobic things happen. Personal ads give people a place where they can hide behind anonymity. I found they were blatantly not neutral.

You also claim that children’s literature is not neutral. Can you tell us more about that?

We tend to perceive children’s literature as non-political, but it’s very political. Children aren’t writing it – adults are writing it.

In those “Mother, Father, Dick and Jane” early readers, someone made a decision about the characters’ skin color. Somebody made a decision, whether consciously or not, about their height, how they were going to be dressed, what their hair would look like.

As a brown scholar, as a brown person, I say, 'Where are the brown people in this story?' Well in the Dick and Jane world, they come in the 70s after integration. But it’s interesting to me that they’re described as being just like Father, Mother, Dick and Jane. There was no identity there – they were just sort of vanilla characters 'dipped in chocolate.'

You’ve gotten a lot of national attention for creating a course about the “n-word.” How did that come about?

The class actually started because of very real stuff that was happening. Then-Senator Obama was running for president. And I kept seeing on the Internet where this word was used to refer to him. The first incidence I recall was in a middle school in Florida, where a teacher had written on the board that the acronym 'CHANGE' meant, 'Come Help a N----- Get Elected.'

I started looking to see just how prevalent this kind of blatant personal attack on him was. And there was also this sense that the word was being used in hip-hop. So I said, 'Let’s study this because I want to know what’s really going on in terms of race relations and our national identities and language.' And the way that I could study it was by trying to teach it. It wasn’t a class that was trying to get people to use or not use the word; it was to better understand it in a series of cultural contexts.

People have asked, 'How can you have a whole class on a word?' Well, the class isn’t on a word. The class starts with a word, but the word exists in a context. You cannot talk about a word without talking about historical contexts, without talking about race, gender, class and, in this case, American history. The word is just a series of sounds coming together to make meaning. How, then, is that meaning constructed, by whom, and why? That’s what the course is about.

And now this work is getting international attention.

Yes. I’m in communication with folks in Ghana and Scotland about this word, because people in other places are reading American texts. There’s a hip-hop store in Malawi that’s called “The N-Word.”

What I hear when I’ve consulted people about it in other places is, 'Well we don’t have the same history as Americans.' I’ve been conversing with a student at the University of Edinburgh, whose teacher is an alum of ASU. They were studying an African-American text from the Harlem Renaissance, and the tutor was uncomfortable with the white students reading the n-word out loud with no real understanding of the context.

The students didn’t understand why. Their response was, 'Well this is not our history and so we don’t have the same connection.'

That’s interesting to me, because if we can only connect with experiences that we have lived, then that doesn’t demonstrate our capacity to have empathy or to care about people who have experiences that we haven’t had. And the human capacity is much bigger than that. I mean, we write checks when there’s a tsunami, when there’s an earthquake on the other side of the world. We care about people, fundamentally.

Is that what Project Humanities aims to demonstrate?

Project Humanities allows people to recognize that we are more alike than we are different, and each of us is trying to make sense of our everyday lives and experiences. The big challenge in everyday living is 'talking, listening and connecting.'

What I think makes Project Humanities interesting and a model for other universities is that it involves students, it involves faculty and it involves staff. For example, we sponsored a poetry contest about defining the humanities through couplets that was staff-created and staff-judged.

During Project Humanities launch week in February 2010, students came up with the idea of asking visitors to paint responses to provocative questions on giant sandwich boards: 'Is your tattoo your philosophy of life?' 'How do you adjust your moral compass?' It was amazing to watch different people come up and participate in that. Then we moved those boards around campus and they became public art pieces.

Can you explain the Project Humanities theme of “Perspectives on Place?”

So much of ASU is about place. Where are we as a New American University? What is our place among other institutions? It was also coming out of the headlines – what is the perception of the Southwest generally and of Arizona specifically relative to the Tucson Tragedy, or the ban on ethnic studies, or the signing of SB1070? How can humanities at ASU create a different narrative of what it means to be in Arizona, at ASU and in the Southwest?

But it’s also about the place of the humanities. We formed right after the major crisis in the economy, and a lot of universities were cutting their language programs. Project Humanities, with the university’s support and resources, is the other narrative we want in the headlines locally and nationally. We are doing important and necessary work within ASU and beyond.

How do you respond to universities cutting humanities programs, and to the claim that schools should focus on disciplines that provide job prospects?

Well, first of all, people have jobs in humanities. I recently went to Italy to present at a conference. While there, I also went on a number of excellent research-related cultural tours. The people who led these were art historians. These were people who have jobs and are following their passion for the humanities. They were not on the streets begging; nor were they trapped in high-paying jobs that they hated. So humanities does present possibilities professionally like other fields or disciplines.

But it’s not just that you need a job. You need other things to make you whole. A job can’t – or shouldn’t – make you or be you. Folks lose jobs; we do not want to lose our humanity or our instinctive ability to connect with another person. One of our most popular Project Humanities bookmarks reads, “Humans need meaning, understanding, and perspective as well as jobs.” Humanities allows for meaning, understanding and perspective.

Neal A. Lester is an associate vice president within the Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development. The Department of English is a unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.