ASU study uses new biomaterials for wound healing

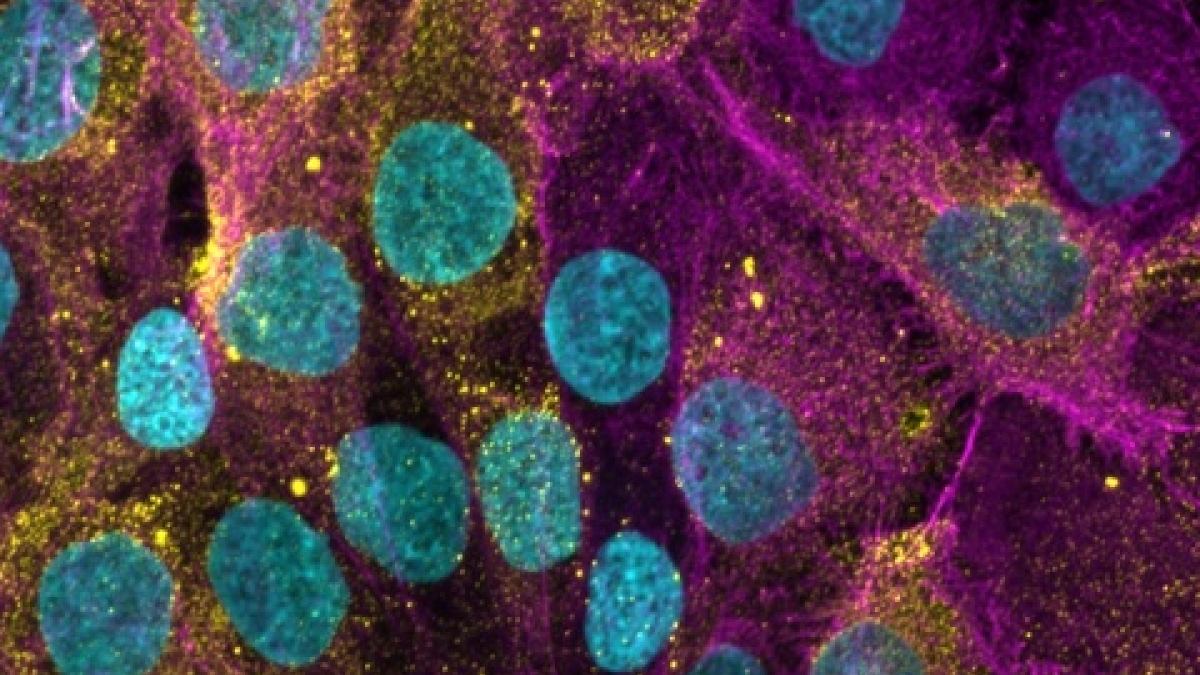

This image shows human skin cells, which form the outermost layer of the skin. The yellow highlights indicate histamine receptor 1, a molecule involved in wound healing and immune responses. The magenta illustrates the structure of the cells’ actin cytoskeleton, which helps maintain their shape, while the cyan represents their DNA, housed in the nucleus of each cell. Image courtesy of the Kaushal Rege Bioengineering Lab

A minor cut often heals within days, vanishing without a trace. Yet, wound healing and tissue repair are complex biological processes, revealing the body’s remarkable regenerative capacity.

In a new study, researchers from Arizona State University explore the wound-healing process in detail, focusing on the role of histamine — a natural chemical that helps coordinate the body’s repair process.

Histamine is involved in allergic reactions, where it causes symptoms such as itching, swelling and runny nose. However, histamine is also essential for regulating the immune system, managing inflammation and aiding wound healing.

The study describes the use of biomaterials — engineered substances designed to interact with living tissues — combined with precisely acting drugs to activate histamine signaling. Applied as wound dressings, these materials enhance healing by selectively activating histamine receptors, promoting tissue repair and the growth of new cells.

The study demonstrates in a mouse model that biomaterial formulations engineered to activate histamine receptors can speed healing when applied to wounds. By addressing challenges such as chronic and slow-healing wounds, biomaterials are paving the way for advancements in regenerative medicine, which seeks to restore or replace damaged tissues and organs.

“Histamine tends to get a bad reputation because of its role in allergic reactions, but it is actually a key player in the repair process. Even small injuries such as a paper cut feel like they itch — that’s the body’s natural healing process using histamine to trigger signaling that begins healing,” says Jordan Yaron, first author of the new study. “There are four different receptors for histamine in our bodies, and in this study we learned that each of these receptors plays a different role in regulating repair and regeneration in the skin. Moreover, we learned we can target these for therapeutic effect.”

Yaron is an assistant professor with the Biodesign Center for Biomaterials Innovation and Translation. He is joined by ASU colleagues with the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

The results appear in the current issue of the journal Biomaterials.

Healing with histamine

Chronic and slow-healing wounds affect approximately 6.5 million people in the U.S. annually and contribute to $20 billion in health care expenses each year. Tissue repair typically follows a carefully orchestrated sequence of stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and remodeling. However, disruptions in these tightly regulated processes at any stage can lead to severe complications, with diabetic foot wound complications showing a five-year survival rate — lower than that of some cancers.

Histamine is an important messenger in the body. It is released by mast cells, found in the dermis — the layer of skin just below the surface. When the body confronts an allergy, injury or infection, histamine acts as a first responder, triggering swelling and redness, which increase blood flow to the affected area. This response helps deliver immune cells and essential nutrients to the site of injury, activating the body’s natural defense system and kick-starting the healing process.

The latest in materials research

To learn more about biomaterials and their critical role in fields like regenerative medicine, click here.

Histamine receptors are cell proteins that respond to histamine, with each receptor playing a distinct role. The four types of histamine receptors are distributed across different cell types: H1 is found on endothelial and immune cells, H2 on stomach lining and immune cells, H3 primarily on neurons and certain endothelial cells, and H4 mainly on immune cells such as mast cells and neutrophils — a type of white blood cell.

While histamine is vital for the inflammatory phase, its level must decrease for the wound to progress to the proliferative and remodeling phases. The proliferative phase is when the body begins rebuilding damaged tissue, forming new blood vessels, collagen and skin cells to repair the wound. The remodeling phase follows, where the newly formed tissue is strengthened and reorganized to restore normal function.

Persistent or excessive histamine activity can lead to chronic inflammation, delayed healing or excessive scarring. Histamine is therefore crucial for initiating the wound-healing process, but its role must be tightly regulated to ensure efficient progression through the healing stages.

Earlier research by the group showed that histamine can be harnessed to modify immune responses and stimulate the growth of new blood vessels, improving biomaterial-assisted wound healing in therapeutic applications. The researchers demonstrated that introducing histamine directly to wounds or combining it with silk-based biomaterials significantly sped up wound closure in both normal and diabetic mice.

The new study explores how activating each of the four types of histamine receptors affects wounds treated with a silk-based biomaterial. Researchers discovered that each receptor triggers a unique immune and tissue repair response, providing new insights into how histamines aid in healing.

Smooth as silk

Silk fibroin is a natural protein found in silkworm cocoons that can be processed into materials for medical use. It is strong, flexible and biocompatible, making it ideal for helping wounds heal and supporting tissue repair.

The silk-based biomaterial used in the study acts as a specialized bandage that seals wounds and actively enhances the body’s natural healing process. It is combined with tiny molecules, called agonists, which selectively activate specific histamine receptors. This activation promotes the growth of new blood vessels, reduces inflammation and directs immune cells toward tissue repair. Together, the silk material and the agonists create an environment where damaged tissues can heal more efficiently and with fewer complications.

The researchers explored the four histamine receptors and found that activating three of them (H1, H2 and H4) helped wounds heal faster. These receptors work by encouraging the growth of new blood vessels, reducing inflammation and helping immune cells focus on repairing damaged tissue. In contrast, one receptor (H3) didn’t seem to affect the healing process.

The study suggests that fine-tuning how these histamine receptors are activated could lead to improved methods for healing wounds. By combining this knowledge with advanced materials like silk-based sealants, the researchers are opening possibilities for treating challenging or chronic wounds, such as those caused by diabetes.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health with grants 01AR074627 to Kaushal Rege and K01EB031984 to Jordan Yaron, as well as the Flinn Foundation Translational Seed Grant 23-06536 to Yaron and Rege.

More Health and medicine

Is ‘U-shaped happiness’ universal?

A theory that’s been around for more than a decade describes a person’s subjective well-being — or “happiness” — as having a U-shape throughout the course of one’s life. If plotted on a graph, the…

College of Health Solutions medical nutrition student aims to give back to her Navajo community

As Miss Navajo Nation, Amy N. Begaye worked to improve lives in her community by raising awareness about STEM education and health and wellness.After her one-year term ended last month, Begaye’s…

Linguistics work could improve doctor-patient communications in Philippines, beyond

When Peter Torres traveled to Mapúa University in the Philippines over the summer, he was shocked to see a billboard promoting Arizona State University.“It wasn’t even near the university,” said…