New study finds previously unreported and persistent super-emitting methane plumes from US landfills

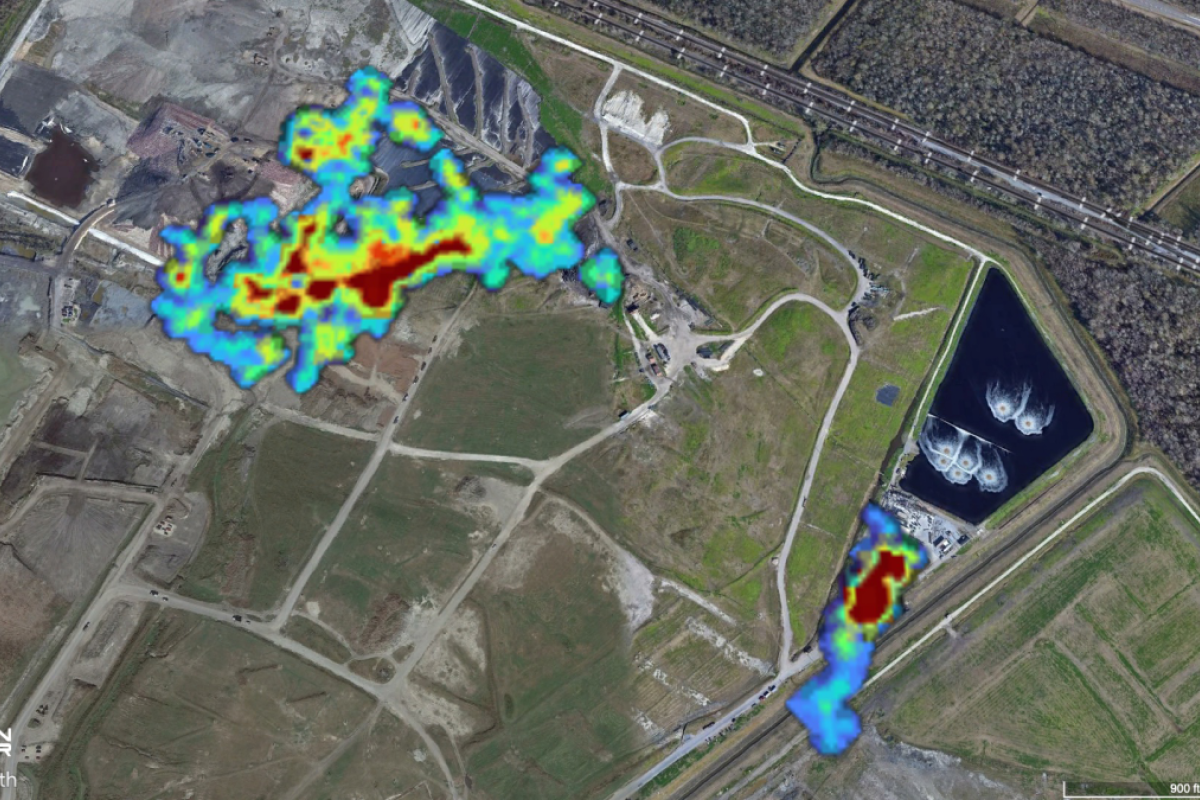

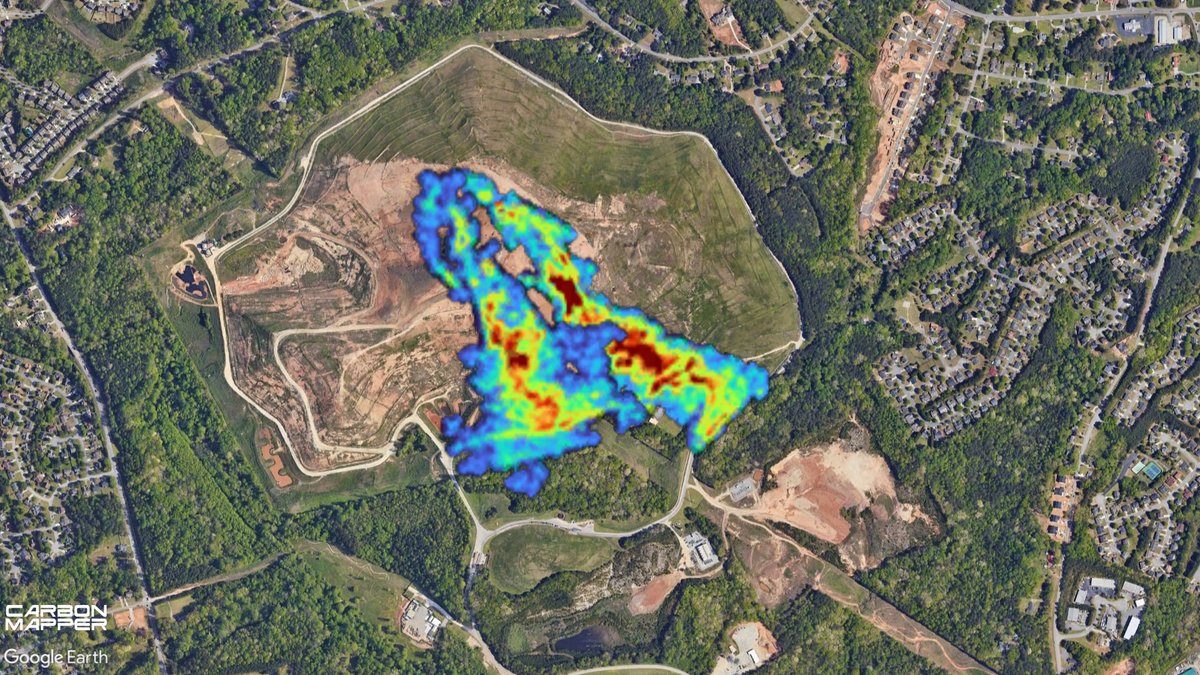

Methane plumes are observed during aerial surveys of a landfill in Georgia. ASU’s Global Airborne Observatory is one of two partner aircraft used to conduct the Carbon Mapper surveys. Photo courtesy Carbon Mapper

In the largest and most comprehensive assessment to date of hundreds of U.S. landfills, scientists from Arizona State University, who are part of a research collaboration with Carbon Mapper, have discovered that many landfills in the U.S. are releasing high volumes of methane and are responsible for a disproportionately large share of pollution from this important sector.

The study, published online today in Science, shows there are significant gaps in landfill leak detection and protocols for quantification. Current walking surveys with handheld sensors are often an ineffective way to completely sample a landfill surface, including methane plume activity that can dominate the facility’s emissions while remaining undetected for extended periods. The findings demonstrate a need for long-term, holistic monitoring in the context of creating climate change mitigation policies.

The research team used direct observations through airborne surveys over a four-year period to survey the landfills. Scientists from ASU participated in this Carbon Mapper-led project, alongside University of Arizona, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Scientific Aviation and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“We’re pleased to have provided the primary data for this important, comprehensive study,” said Greg Asner, director of the ASU Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory. “This kind of collaborative work is crucial to discovering previously unreported sources of methane, and to providing key information to site managers and policymakers so they can promptly address emissions.” Asner is a core member of the Carbon Mapper Coalition and his work on the ASU Global Airborne Observatory is key to gathering methane data for the program.

“Addressing these high emission sources and mitigating persistent landfill sources offers a strong potential for climate benefit,” said Dan Cusworth, Carbon Mapper program scientist and lead author of the paper. “The ability to precisely identify leaks is an efficient way to make quick progress on methane reduction at landfills, which could be critical for slowing global warming.”

Landfills are considered the third largest source of human-caused methane emissions in the U.S. In 2021, they were responsible for 14.3% of methane emissions — the equivalent of greenhouse gas emissions from more than 23 million gasoline-powered passenger vehicles driven for one year, according to the EPA.

Despite the negative climate impact of landfills, societal understanding of these emissions is largely limited to model-based estimates, and the industry remains under-addressed compared with other large methane sources such as oil and gas. Traditional surface-based surveys that use handheld methane sensors provide an incomplete picture of emissions. This is due to factors such as limited access to many sections of active landfills as well as logistical and personnel safety reasons.

To help fill these gaps, the research team used advanced aircraft to conduct the largest direct measurement-based survey of active municipal solid waste landfills to date, from 2018 through 2022. This included aerial surveys, led by Carbon Mapper and Scientific Aviation, of over 200 active U.S. landfills that participate in the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (20% of approximately 1,200 reported open landfills). The team used partner aircraft — including ASU’s Global Airborne Observatory with the Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science and NASA JPL’s AVIRIS-NG — to conduct the surveys.

Key findings

Evaluating this large dataset yielded insights that the researchers say site owners and operators, policymakers, regulators and society can use to better assess and act on landfill emissions.

First, 52% of surveyed landfills had high-point source emissions, with methane emissions exceeding 100 kilograms per hour. This far surpasses the 0.2% to 1% detection rate observed for super-emitters from surveyed oil and gas infrastructure in California and the Permian Basin.

Second, these methane plumes are generally more persistent compared with their counterparts in oil and gas production. For landfills where researchers observed emissions, 60% had plumes that continued over months or years. These prevailing emissions totaled 87% of all quantified emissions in the study. Comparatively, most methane super-emitters in the oil and gas sector are related to irregular, short-duration events.

Additionally, the quantified emissions in the study find little agreement with national reporting frameworks. The study notes a misalignment between observed and reported emissions. This indicates that current methods used to report facility emissions, such as the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, are missing or misrepresenting large sources of methane. On average, aerial emission rates were 1.4 times higher than those in the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program.

Finally, there are significant differences between existing protocols for measuring methane and actual landfill leak detection. Current walking surveys with handheld sensors are an ineffective way to completely sample a landfill surface, including super-emitter activity that can dominate the facility’s emissions while remaining undetected for extended periods.

Next steps

Looking forward, the researchers say this study reveals the need for a more comprehensive and effective monitoring strategy to measure, quantify and act on methane emissions at landfills. They also say additional resources, including the Carbon Mapper Coalition satellite program, can help provide solutions for measurement challenges.

Advanced monitoring strategies, such as remote sensing from satellites, aircraft and drones, can provide a more accurate picture of landfill methane emissions. When combined with improved ground-based measurements, remote sensing can provide consistent, comprehensive measurements to better inform models, guide mitigation efforts and verify emission reductions.

The coalition’s first Tanager satellite, launching later in 2024 as part of a public-private partnership between Carbon Mapper, Planet Labs PBC, NASA JPL and others, is uniquely designed and optimized to detect methane at landfills. Carbon Mapper is also conducting a multiyear initiative to assess thousands of high-emitting solid waste sites globally, using remote sensing technologies to establish a methane emissions baseline for managed landfills and unmanaged dumps. This includes U.S. landfill aerial campaigns planned for 2024.

The emissions data is publicly available to a wide range of stakeholders, including major waste management companies, city and county governments, and the public at large. The research team says the data empowers municipalities to mitigate emissions and make informed decisions that maximize methane capture.

Annabelle Blair contributed to this article.

More Environment and sustainability

From K–12 to corporate upskilling, ASU guides learners of all ages to design a sustainable future

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series exploring how ASU tackles complex problems to create a thriving future.When Kennedy Gourdine was a high school student in Maryland, she conducted…

Sustainability leadership in action

Editor's note: This story was originally featured in a special edition of ASU Thrive magazine.ASU alumni are making an impact. From city government to corporate leadership, they’re working in every…

Sustainable plant-based polymers could replace endocrine-disrupting plastics

We humans produce enormous volumes of plastic waste, and we recycle very little — just 14% of the 590 billion pounds discarded in one recent year, worldwide. To make matters worse, exposure to…