Ginette Rossi was exhausted and defeated.

She had been a teacher for 15 years, but as the 2017–18 school year began, her passion for the job had given way to resignation.

She was upset about the political climate that was trending in the country, the strict curriculum under which teachers had to operate and the apathy she saw in her students’ faces.

“I was ready to quit,” Rossi said. “I was like, ‘I just can’t do this anymore.’”

Fast forward to 2023. Rossi, a fourth-year doctoral student in the Department of English at Arizona State University, is sitting in her classroom at the Arizona School for the Arts in downtown Phoenix. She’s beaming, so excited that her words tumble out of her mouth, one after another, as if she can’t wait to tell her story to her visitor.

Two weeks earlier, Rossi was named the recipient of the K–12 Humanities Educator Award from Arizona Humanities, which recognizes an educator who engages students with the humanities through teaching in the classroom or leading humanities-based school programs.

Rossi was humbled by the recognition and $2,500 prize — “you don’t really set out as a teacher to get accolades,” she said — but the award is not why her enthusiasm is off the charts.

Instead, she said she's indebted to ASU and the instructors who rekindled her love for teaching by showing her a different way to teach.

Ginette Rossi joins her 11th-grade college prep English class in a writing assignment on Monday, Oct. 23, at the Arizona School for the Arts in Phoenix. Rossi has been given this year's Arizona K–12 Humanities Educator Award. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

“I think a lot of times the narrative of teachers is that we are exhausted. We’re underpaid. We don’t have inspiration. We’re told what to do,” Rossi said. “But I think what ASU allowed me to do was give (my students) a version of a teacher that is the true heart of a teacher.”

That transformation began when Rossi, after being hired by the Arizona School of the Arts to teach fifth grade English and be a reading specialist, received an email from ASU about its master’s degree in English education.

Rossi applied for the program, was accepted and — as she switched roles and became a student for Department of English professors like Jessica Early and Gabriel Acevedo — discovered a different way to teach.

Rossi had always been told that a teacher was supposed to follow the curriculum, come up with a lesson plan and grade the students. But Early, Acevedo and other ASU professors challenged her:

How would she get her students to participate? How would she uncover their stories and their wonderings?

“They talked about going into the community as a teacher, spending time in the community and learning about your students rather than just taking whatever the school put in front of you,” Rossi said. “They also taught me how to ask students what they want to learn about.”

In Early, who Rossi calls her “person,” Rossi saw the kind of teacher she again wanted to be. Enthusiastic. Innovative. Meeting students where they are in life instead of dictating where they should be.

“I sort of looked at her and thought, ‘Wow, this is how I want to teach. I never want to lose that,’” Rossi said.

Rossi was determined to instill her love of books into her fifth-grade students. She thought of her childhood and how books were an escape from a “crazy childhood.”

There was just one problem.

“As I was pulling the books out for the class, I was like, ‘Well, there’s not a diverse character in any of these stories whatsoever,’” Rossi recalled. “But in front of me are all these diverse students.”

One night, in Early’s 541 Teaching Texts: Methods of Teaching Secondary Reading class, Rossi read an article from two Kent State University educators who had done research examining why high school students didn’t like to read. They determined that creating an environment that encourages reading — rather than teachers simply assigning books — was paramount.

Rossi decided to put her own spin on the problem. The next day in class she told her students what her ideas were and asked what ideas they had.

“Let’s put it together and reclaim it as something different,” she said.

“What if,” the students replied, “we were able to read anything?”

Thus, the Book Bistro was born.

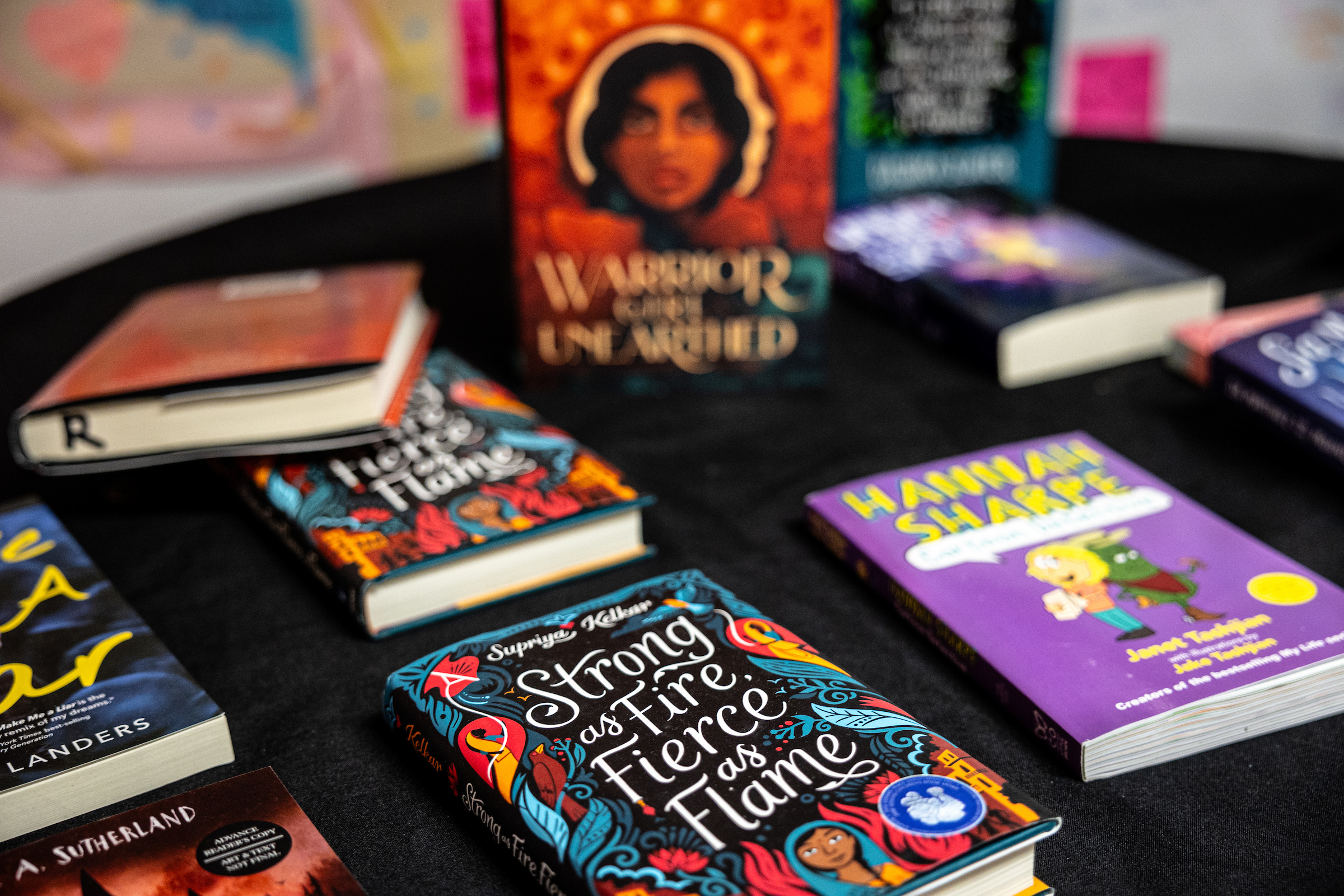

A collection of books in Rossi's 11th-grade English classroom at the Arizona School for the Arts in Phoenix. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Rossi told her students they could read anything — novels, short stories, magazines, recipes, even comic books — as long as each reading assignment lasted at least 20 minutes and they were reading three different pieces each quarter. At the end of each quarter, they got together in a coffeehouse-style atmosphere to talk about what they had read and celebrate the accomplishment. One quarter they had hot chocolate and cookies. Another quarter was doughnuts with sprinkles.

“Before I knew it, the kids were taking control and designing the parties,” Rossi said. “I mean, it just blew up.”

Rossi said the students started sharing books with each other and, in turn, discovered things in common they didn’t know they had.

“One of my fifth graders told me, ‘I met my best friend through the Book Bistro,’” Rossi said.

Rossi told other teachers about the Bistro. Then, she presented the idea to the National Council of Teachers of English annual conference. Today, more than 30 schools across the country use the Book Bistro concept.

“I never planned it this way,” said Rossi, who now teaches an 11th-grade prep English class at Arizona School for the Arts. “It just happened.”

All because, at ASU, she found a way to love teaching again.

Top photo: Ginette Rossi greets her students before her 11th-grade college prep English class Monday, Oct. 23, at the Arizona School for the Arts in Phoenix. The Department of English doctoral student won the Arizona K–12 Humanities Educator Award for creating a reading program called Book Bistro. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…