ASU professor’s memoir about her painful childhood gives a voice to the women of Rastafari

Update, March 22, 2024: “How to Say Babylon” by Associate Professor of English Safiya Sinclair has won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Autobiography. The awards are, according to the New York Times, “among the most prestigious literary prizes in the United States. Unlike other major awards, the recipients are chosen by book critics instead of committees made up of authors or academics.”

Safiya Sinclair grew up in Jamaica, her life defined by her father’s authoritarian Rastafarian beliefs.

It was a life of rules and regulations, she said, so constricting that Sinclair left Jamaica to discover who she was and pursue her love of writing.

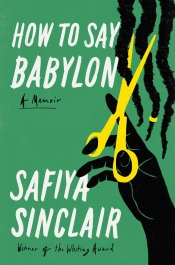

Now, Sinclair, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s Department of English and the recipient of the 2016 Whiting Award for poetry, has gone back to Jamaica with her new book, “How to Say Babylon: A Memoir,” which will be released Oct. 3. The book describes Sinclair’s “struggle to break free of her rigid Rastafarian upbringing, ruled by her father’s strict patriarchal views and repressive control of her childhood.”

RELATED: Jenna Bush Hager chooses Sinclair's book as October 2023 Read With Jenna pick

ASU News talked with Sinclair — who is scheduled to appear on "The Today show" on Oct. 3 and Oct. 25 — about the book, her father’s reaction to her writing and why she decided to write about her upbringing.

Editor's note: The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Question: What made you decide to tell your story?

Answer: It was really important for me for several reasons. I think that a lot of people have a very narrow view of Jamaican culture, of Rastafari culture and of Rastafari history. I knew going in that would be one of the main things that I would have to kind of tackle in the book.

Most people outside of Jamaica seem to think that Rastafari is a thing that defines Jamaica when, in actuality, the Rastafari are historically a persecuted minority. They make up less than 1% of the Jamaican population. They’ve always faced this decades-long history of being outcasts, of being persecuted, of being kicked out of their homes and abandoned by their families. I also think most people, when they think of Rastafari, they perhaps have an image of a man. Most people don’t envision Rastafari as a woman or a young girl. What are their lives like? What is it like growing up as a young woman or an adolescent inside Rastafari culture? So I really wanted to kind of give voice to the women of Rastafari.

Q: This is a very personal book. Was there any trepidation about writing it and bringing up painful memories?

A: Of course. I had no idea what it would be like to kind of revisit some of those moments from my adolescence. A lot of them were fraught because once I started growing up, I began to question some of the rules. Inside Rastafari culture, it’s very strict and very patriarchal. A lot of the rules my father imposed on me and my sisters and my mother were different than the rules on Rastafari men. As I started to grow older I began to question why these rules are different. That led to a lot of clashes between me and my father. So, eventually, I chose to leave the Rastafari religion. I cut my dreadlocks, which is this kind of important sacred marker of Rastafari, but also not a choice.

Q: You mentioned the rules you had to live under. What were some of those rules?

A: We had to keep our arms and knees covered. A lot of Rastafari women had to keep their heads covered. Opinions were not encouraged. Silence and obedience were seen as the highest marker of a woman’s virtue. As I grew older, I didn’t fit into that box. Once I cut my dreadlocks and then my sisters did, and then my mother did, a lot of things happened from there. That changed the trajectory of our family’s life forever.

So, yeah, I did feel like, “OK, how will this be to go there and to write about this and to write about it in a different way than I could write about it in poetry?" I had to have scenes of dialogue and a long narrative arc. I couldn’t really escape it. There were moments where I was writing and was kind of overcome with emotion, and I just had to write through it, write through the tears to sort of get to the other side, to the catharsis.

Q: You started the book in 2013 but put it aside because you didn’t want to write from a place of anger. How did you get past that anger and eventually come back to writing?

A: I was angry for a long time but, I think, even more hurt. Because after we all cut our dreadlocks, for a long time it was hard for my father to accept. Perhaps he saw me as kind of the root of the ruin. ... I knew had to leave Jamaica. No one ever wants to have that realization, that your survival depends on leaving your home.

It wasn’t until 2018 when I returned home and had a poetry reading in Jamaica. This was the first time I had gone home since I left. I invited my father and my brother to come and hear me read poetry for the first time. I read it directly to him from the stage, and I was hoping he would hear my voice for the first time in the hope he could see us as equals, and that I have something of value to say. I was so nervous. I read the poem and I said, “I hope you can hear me.” Then, when I got off the stage, my father embraced me. He whispered in my ear, “I’m listening.” And it was in that moment that I felt that true catharsis. I felt like, “OK, I think I can begin.” And that’s when I began.

Q: For those who don’t know, what does Babylon represent in Jamaica?

A: For the Rastafari, Babylon represents all the corrupt and immoral influences of Western culture and ideology. That includes capitalism, colonialism, imperialism, Christianity and all of those long, systemic chains that they feel have been oppressive to Black people. That always included the government and the (British) crown.

So my father began with good intentions of wanting to protect us from what he saw as these corrupting influences. This idea of our purity was one that kind of defined my childhood and womanhood. It involved what you could eat, what you could wear, what you could think. We could only eat a specific diet, kind of like a vegan diet. No meat, cheese, dairy, no eggs, no salt, no pepper. The idea was that your body was supposed to be a Jah (the singular god in Rastafari) temple, and you shouldn’t corrupt it. And, of course, women had to keep themselves covered as a preservation of their purity.

But as we grew older, I think my father’s paranoia and obsession with Babylon worsened. We were kind of kept at home, especially my sisters and me. We weren’t really allowed to have friends or have company come over. We weren’t really allowed to leave the house except to go to school. Eventually, in my teenage years, we became kind of recluses. My brother had more freedom to go about the town and have girlfriends and live kind of a normal teenage life, but that wasn’t quite allowed for me or my sisters. I think our father thought perhaps that, as women, we were more susceptible to corruption.

Q: You interviewed your father, Djani, for the book. What was that interaction like?

A: I mostly asked him about his own adolescence. I wanted to know how he came to choose Rastafari. What was his journey to Rastafari, which began as a teenager and then, of course, changed the shape of my life. To tell my story, I had to tell that story. It was illuminating and also surprising, probably, for both of us, because I think it was the first time that anyone had ever asked my father to tell them about his life. He even got emotional, which is rare for him. I think he came to the realization that he was carrying a lot of wounds from his own adolescence. His mother was a Christian, and she threw him out when he became Rastafari.

Q: Did knowing what he had gone through help you understand him more?

A: I think it did. He never knew his father. He has an estranged relationship with his mother. He was always seeking some kind of belonging. He had always been kind of trying to belong to a family or something he felt rooted in. I began to understand that more when I talked to him.

Q: Has he read the book?

A: I gave him a copy, and I know he started reading it, but I don’t know if he’s finished it. When I gave him the book, he asked me, “Can I read this?” And that was the first time he ever asked to read anything I had written. I said sure. I thought it was important for him to read it before anyone else did. So then he began to read it and then he was calling me, trying to correct things. And I was like, “The book has gone to print.” So I said, “Can I get you to promise me something? Can you promise me that you won’t call me to talk about the book until you’ve finished it?” And he said OK.

Q: And you’re still waiting for that phone call?

A: I’m waiting. I told him it would be hard for him to read, but he should read it to the end.

Q: I know this is a personal story for you, but is there a message you hope readers get from the book?

A: Even though the story is so particular to me and how I grew up, I think anyone who had a difficult relationship with their father or with their parents in any kind of fundamental religious space will see themselves in this book. And, of course, any young woman or young girl who herself has felt for a time that she was diminished should feel that she has a voice and she, too, can celebrate her womanhood.

More Arts, humanities and education

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…

ASU instructor’s debut novel becomes a bestseller on Amazon

Desiree Prieto Groft’s newly released novel "Girl, Unemployed" focuses on women and work — a subject close to Groft’s heart.“I have always been obsessed with women and jobs,” said Groft, a writing…