The future of US rangelands: Choices that reshape our landscape

A black bull roams the open range along Highway 186 in Cochise County, Arizona. Photo courtesy Adobe Stock

Despite inaccurate media portrayals of sprawling, uninhabited areas, rangelands are home to 30% of our planet’s human population and 50% of the world's livestock — making them indispensable for livelihoods and food security. However, global conversations about conservation and climate change often do not mention these landscapes.

Osvaldo Sala, Regents Professor and director of the Global Drylands Center at Arizona State University, hopes to change that.

Sala recently co-authored a paper titled "Supplying Ecosystem Services on US Rangelands" that sheds light on the potential crossroads facing these ecosystems as they are confronted with evolving environmental and societal changes. The paper was published in the research journal Nature Sustainability.

Sala said protecting and managing rangeland ecosystems is essential for mitigating climate change, adapting to its impacts, preserving the unique biodiversity and sustaining future livelihoods for these regions.

“The perception people have is that rangelands are wastelands; they are not,” Sala said. “They are very rich in terms of biological diversity, even more so than temperate zones.”

The paper uses scenario assessments to bring much-needed awareness to the future of rangelands, also referred to as drylands, and anticipate how natural and human-driven factors might influence these in the years to come.

“Motivations for the paper are two-fold,” said David Briske, Regents Professor at Texas A&M University and first author of the publication. “First is to increase recognition of the value of ecosystem services provided by rangelands. The second is to encourage long-term planning and policy regarding future outcomes on rangelands.”

The paper is written through a national lens, but the primary change drivers that impact rangelands the most can be found across the world. The first driver of change is the warming of our planet, which brings with it a loss of biodiversity, increased drought and wildfires. The second change driver is social demand, which can vary. For example, one group may prefer to use a certain stretch of rangelands for cattle production while another may want to use that same land for recreational purposes.

“We sought to integrate social and environmental considerations into a synthetic, forward-looking assessment,” said Nathan Sayer, a professor from UC Berkeley and co-author of the paper. “By synthesizing perspectives from a large number of experts, the method aims to identify key variables, generate insights into their interactions and bound the range of probable future outcomes.”

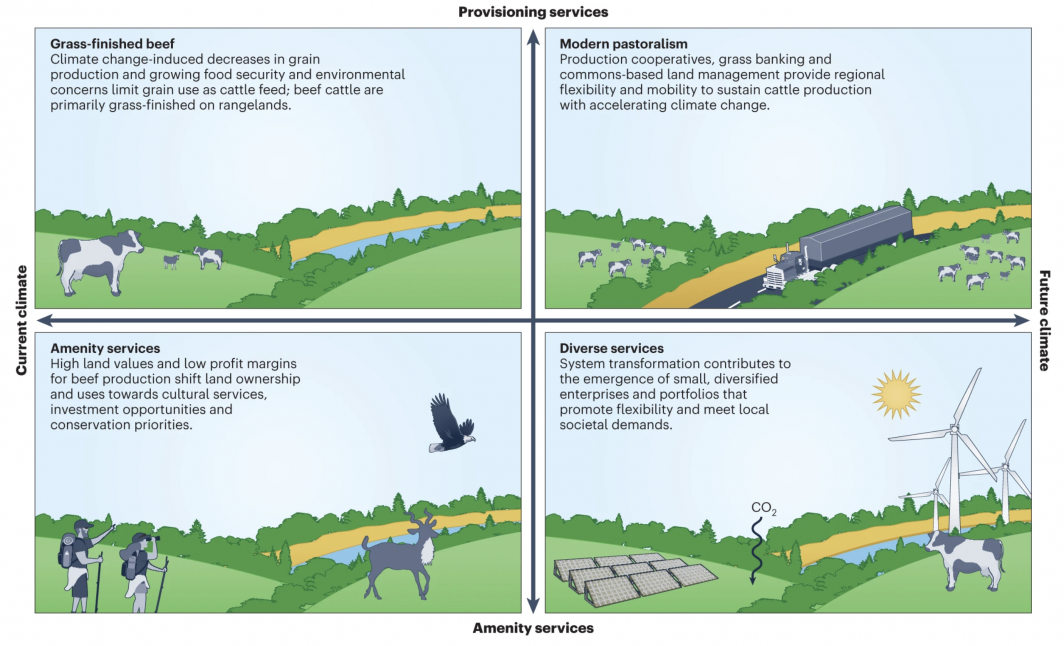

Four distinct scenarios emerged from this assessment: two maintain rural communities by sustaining the prevailing ecosystem service of beef cattle production, and two transform rural communities through expansion of renewable energy technologies and infusion of capital for the provisioning of amenities, such as recreation or ecotourism.

The first scenario highlights the importance of grass-finished beef production, which could provide a sustainable and ecologically-friendly alternative to our current unsustainable beef production practices. In the second scenario, individual ranches may struggle to adapt to the future changing climate conditions and will shift toward a modern kind of pastoralism.This is already a reality in California, where approximately 50% of the state’s calf crop is annually relocated to grazing lands and feed yards out of state within a 12-week period.

The third scenario will move from traditional agricultural models to services prioritizing ecological sustainability. These services might include carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change, renewable energy generation and conservation efforts. This scenario encourages a more diverse portfolio of ecosystem services. Finally, the last alternative scenario will shift from traditional provisioning services to cultural ecosystem services, including recreation, ecotourism, hobby ranching and habitat restoration.

Plausible future scenarios for U.S. rangelands. Illustration by Megan Joyce

“These scenarios are not forecasts.” Sala said. “The idea is not to forecast the future, but to identify alternative pathways, providing valuable insights for decision-makers.”

These scenarios provide a framework for discussing how rangelands may evolve under various circumstances, helping policymakers and stakeholders make informed decisions about their management and use. As the climate shifts and people’s demand for the services provided by rangelands evolve, our ability to proactively plan and adapt becomes more vital.

“We will live in future conditions, so we must anticipate and plan for them. The central message is to emphasize future outcomes so that food and energy security, environmental quality, and the cultural identity of rangelands can be effectively managed and equitably prioritized,” Briske said.

The use of scenarios in this paper demonstrates the connection between actions and outcomes, Sala said. He has worked in developing scenarios for over 20 years, and his previously published work “Global Biodiversity Scenarios for the Year 2100” has served as a landmark for global decision-makers.

Through his work at the Global Drylands Center and his contributions to the School of Life Sciences and the School of Sustainability, Sala studies drylands and their role in our planetary systems. He said that as a respected higher education institution, ASU is uniquely positioned to lead efforts to understand and fully explore the potential of drylands in our changing world. He points to ASU’s charter, which states the university’s responsibility to serve its community: a community located on drylands.

“We are here,” Sala said. “We have the opportunity to excel in the study and research of drylands. It’s not only a responsibility, it’s a great opportunity.”

Written with contributions from by Anaissa Ruiz-Tejada, science writer for the School of Life Sciences, Katelyn Reinhart, communication specialist for the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory, and Dominique Perkins.

More Science and technology

How AI is changing college

Artificial intelligence is the “great equalizer,” in the words of ASU President Michael Crow.It’s compelled industries, including…

The Dreamscape effect

Written by Bret HovellSeventh grader Samuel Granado is a well-spoken and bright student at Villa de Paz Elementary School in…

Research expenditures ranking underscores ASU’s dramatic growth in high-impact science

Arizona State University has surpassed $1 billion in annual research funding for the first time, placing the university among the…