Dispelling myths about being deaf. Examining poverty porn. Reflecting on a Texas town torn apart when a mosque is burned to the ground.

Those are just some of the topics that will be discussed during the fall series of Project Humanities, an Arizona State University initiative that brings together individuals and communities to facilitate conversations about issues in the world.

The fall series begins Thursday from 6 to 7:30 p.m. at the Tempe History Museum with "Poverty Porn 101," which will examine what issues arise when influencers drive through and film encampments of unsheltered people. All of Project Humanities’ events are free to the public. The event schedule can be found here.

ASU News talked with Project Humanities Founding Director Neal Lester, who is a Foundation Professor of English at ASU, about the fall schedule.

Note: Answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Question: For people who don’t know, please explain what Project Humanities is.

Answer: There’s a series of diverse formats where there’s workshops, panel discussions, our Hacks for Humanity event, homeless outreach, lectures, symposiums. … The idea is how do we create a space where people can talk about disciplines, across generations and across professions around issues that matter.

Q: Your first event is Thursday with "Poverty Porn 101." What will be discussed then?

A: This is a workshop that grew out of a previous program that Project Humanities did about two years ago that covered everything from tourism and voyeurism and all these kinds of structures that create spaces where typically wealthy people go to these poor places as though they’re on field trips, and they feel good about themselves and the experience. They may or may not write a check, and then they go on with the rest of their lives.

Through our homeless outreaches, we take pictures of our clients, and the idea was that we’re showing people, “Oh, look at what we’re doing.” I have since learned that we weren’t asking for permission, and we were actually looking for the thing that showed the greatest need in order to show us sort of swooping in and saving folks. So, this is as much about an evolution of how we try to talk about our clients in the homeless outreach to how this becomes something larger at institutions.

There’s a certain kind of narrative that causes people to write checks. And what we’re going to do in this workshop is go beneath those narratives and those images that really become more about the person observing than the people trying to be supported.

Q: You have a wide range of voices in your workshops and panel discussions. How crucial is that?

A: It’s essential. We want to create a space where people can start looking at what we disagree with through the lens of people we don’t often have anything in common with. At our Hacks for Humanity event (Oct. 6–8), I’m looking at judges for the competition. I’m asking community college presidents to be judges. I’m asking people at the multicultural center downtown to be judges. I’m asking somebody from the Phoenix Suns. To me, that kind of diversity is not just about representation, but about the whole experience of diversity.

Q: Is one of the goals of these events to get people to maybe look at issues in a way they haven’t done before?

A: That is exactly what it is. All we want people to do is think about something differently than when they came into our space. We are not telling people how to think, but we’re encouraging people to think. It’s making this an intellectual experience. It’s also about bringing more compassion to whatever that event is. One example is the PBS partnership screening we had of “Love in the Time of Fentanyl.” I was one of those who thought that somehow if you create a space where people essentially could shoot up safely, that we were somehow encouraging that. And, so, learning more about the issue from the documentary and looking at it from a slightly different perspective convinced me very easily that people who overdose aren’t trying to die.

People who are overdosing are people who have an addiction. And if you can keep people safe, then you can bring some compassion to this addiction.

Q: On Oct. 19 you have a workshop titled “What’s in a Name?” — what is that about?

A: Everybody has a name, and that name connects you to someone else, whether it’s a family name or a name that you’ve given yourself, or a nickname or a pet name. There’s something about naming that also identifies people’s humanity. And it’s in this moment where people refuse to use correct pronouns or changing names, particularly if there are names that we can’t pronounce. This happens with international students a lot. If you can’t pronounce it, we’ll name you John or Scott because that’s easier. So, we’re looking at the psychology of naming as well as the politics of naming.

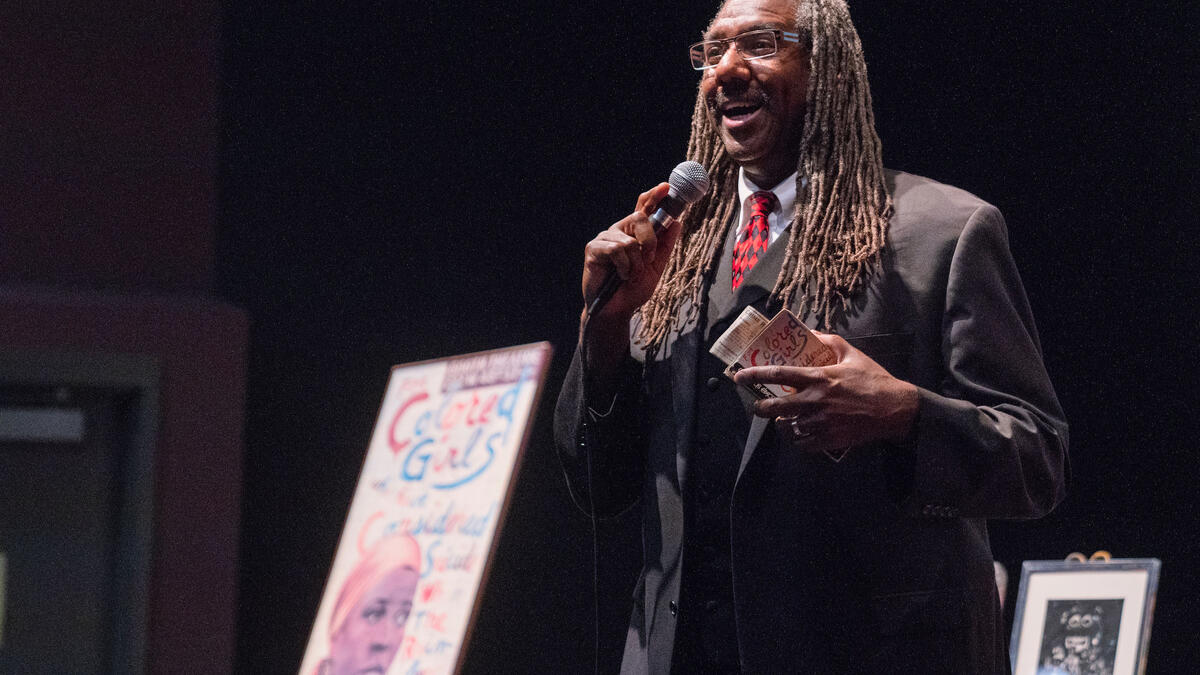

Top photo: ASU Professor Neal Lester speaks at a Project Humanities event honoring the work of the late poet and playwright Ntozake Shange in 2019. Photo by Marcus Chormicle/ASU News

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…