Conserving Costa Rica's big cats

A jaguar resting on the floor of the Costa Rican forest. Photo courtesy Jan Schipper

Editor's note: This is the first in a series of Q&As highlighting Arizona State University researchers working around the world this summer. Read about tool excavation in Africa, a bioarcheologist in Cyprus and motorbike research in Vietnam.

There is a lush, tropical forest on the west coast of Costa Rica, where North and South America merged more than 3 million years ago. It’s home to the largest spotted cat species in the Americas — the powerful and elusive jaguar.

And for the past 20 years, in a research station in the country’s Cordillera Talamanca mountain range, Arizona State University wildlife ecologist Jan Schipper has worked to protect these fascinating felines.

The Costa Rican forest once stretched across the Central American country, providing ample grounds for jaguars to roam freely, find food and sustain their species.

As rainforests were converted to farmlands, the jaguars’ habitat has diminished, reducing prey and forcing the animals to look to livestock for food. Naturally, this shift made them an adversary to the area’s agriculture community.

This is one of many problems Schipper is working to solve. It is a complex conservation collaboration involving the government, researchers and local community members.

Schipper and his team, together with Garth Paine, an acoustic ecologist at ASU’s School of Arts, Media and Engineering, have set up a gunshot detection program throughout the rainforest, which can immediately direct guards to poachers on the prowl.

Schipper is also is working to create a corridor that connects La Amistad International Park (on the Continental Divide of the Americas) with Corcovado National Park (on the Pacific coast) to create a protective pathway that will enlarge the jaguars’ habitat. Overpaths and underpaths will circumvent the Pan-American Highway, help wildlife populations navigate a human-dominated landscape and reconnect isolated jaguar populations on both sides of the country.

Schipper, an associate professor in ASU’s School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences and a research associate at the Phoenix Zoo, returns to Costa Rica this month. ASU News caught up with scientist to learn about his work and plans for this trip.

Note: Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Question: You’ve worked in jaguar conservation for more than two decades. What drew you to this work?

Answer: Having worked in Costa Rica for a lot of my career, I started with smaller cats — like the margay, which is the size of a house cat and very arboreal. Then I studied the oncilla — which interestingly only lives in the cloud forests of the Cordillera Talamanca mountains.

And I just worked my way up the food chain to the puma and finally the jaguar, which is the biggest cat in the Americas.

My greatest interest was in the national parks in the area and how effective they were in containing the entire ecosystem.

Q: What is the connection between the survival of the jaguar and that of the ecosystem?

A: As a top predator, jaguars have a “top down” influence on food webs, and, as such, control the health of the prey populations. We have seen this very clearly in restoring the wolf population to Yosemite (National Park); entire ecosystems recover after the top predator is reinvigorated.

Jaguars can thrive in many types of habitats and recover from decades of hunting and habitat loss.

If we can create "jaguar friendly" communities by both reducing hunting of jaguar prey species and reducing retaliatory killing of carnivore species, these magnificent cats can return to their native habitats — including Arizona.

Q: How much of the jaguar population has been eliminated?

A: Satellite imagery indicates habitat loss, so we expect less jaguars overall. That combined with hunting, and the picture looks pretty gim.

The largest population remains in La Amistad International Park, where we work. But the populations in Central America are still much worse off than in the Amazon. Areas we considered safe havens a decade ago are now being seriously challenged.

Q: Hunting is a huge problem. Why is poaching on the rise?

A: In Costa Rica — which is close to the Panama Canal, an Asian trade route — a spotted jaguar can be worth as much as $10,000, and a black (melanistic) jaguar is worth about $20,000. They are taken to China and sold as parts. That's enough incentive to keep local poachers hunting — a year's salary in one kill. Also a lot of North Americans and Europeans like to come shoot things in Costa Rica ... and jaguar is top on the menu.

So between sport, subsistence by Indigenous people and retaliatory killing ... there are a lot of jaguar mortalities.

Q: How is your team putting a stop to that?

A: Our research is designed to reduce jaguar poaching and educate poachers and their families, many of which we try to employ to work for us in tracking wildlife.

In the next year, we are creating a wildlife path across the Pan-American Highway and a network of private landowners under the “Jaguar Friendly” label to produce coffee and cacao to support the jaguar movement. Our goal is to create stepping stones so jaguars can move across the human dominated landscape between national parks. We do this by empowering and not displacing communities. Reconnecting people with nature is as important as reconnecting parks.

We know that jaguars are coming back in a few places unexpectedly — including Arizona. It speaks to the broader resilience of jaguar populations to rebound if given the chance. As we see in Costa Rica and elsewhere, if we just stop killing them, they will gradually come back and often learn to adapt.

More Science and technology

New research by ASU paleoanthropologists: 2 ancient human ancestors were neighbors

In 2009, scientists found eight bones from the foot of an ancient human ancestor within layers of million-year-old sediment in the Afar Rift in Ethiopia. The team, led by Arizona State University…

When facts aren’t enough

In the age of viral headlines and endless scrolling, misinformation travels faster than the truth. Even careful readers can be swayed by stories that sound factual but twist logic in subtle ways that…

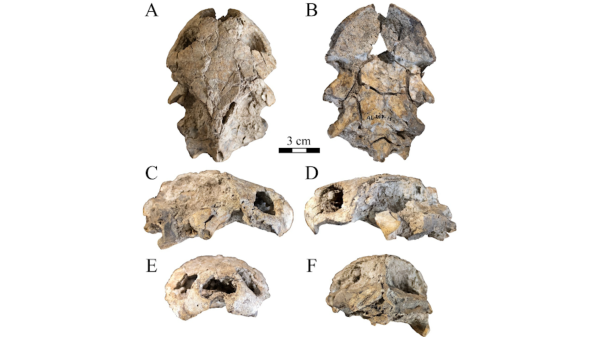

Scientists discover new turtle that lived alongside 'Lucy' species

Shell pieces and a rare skull of a 3-million-year-old freshwater turtle are providing scientists at Arizona State University with new insight into what the environment was like when Australopithecus…