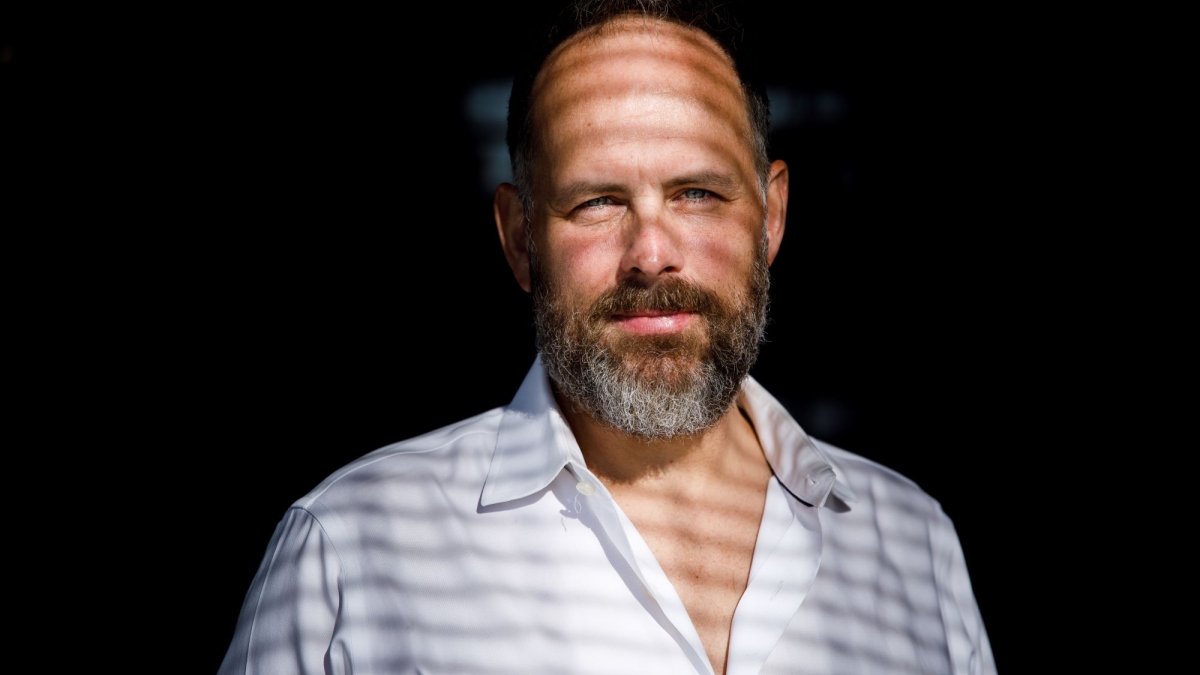

Gaymon Bennett, associate professor for the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, believes that the study of ethics is best exhibited not just through the subject matter of research, but through embodied, collective practice. This is a key perspective at the core of his work as the new director of the Arizona State University Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics.

Bennett has served as the associate director for the Lincoln Center since 2020, supporting the center’s move to the humanities under The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and its shift in focus to the topics of humane technology and ethical innovation.

“We are fortunate indeed to have an ethicist with so deep and varied a background at the helm of the Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics,” said Jeffrey Cohen, dean of humanities. “I have worked with Dr. Bennett closely over the years and have come to admire his brilliance, his field-crossing knowledge and his good heart. Dr. Bennett is a one-of-a-kind scholar-practitioner who will further and deepen the mission of a center — the work of which has never been so urgent.”

Bennett earned PhDs in cultural anthropology and philosophical theology from UC Berkeley, with a research focus on the impacts of modernity on contemporary experiences of science and religion. His connections within ASU are far reaching, with appointments in the Institute for the Future of Innovation in Society, the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict and the Center for Jewish Studies.

Bennett’s work interfaces with both humanities and tech innovation, and has interrogated the culture and politics of knowledge production by exploring shared conceptual frameworks and collaborative empirical inquiry. During his tenure at ASU, Bennett’s work has been supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation, The Templeton Religion Trust, The American Council of Learned Societies, The U.S-Israel Binational Science Foundation and others.

His emphasis on collaboration and experimental practice as keys to ethics are demonstrated throughout the work of the Lincoln Center. The center’s renewed vision for ethical innovation in 2020 coincided with the inception of its design studio model: a process at the heart of the center that seeks to rethink how research gets done, how findings get shared and who gets to participate. This research model consists of co-designed movements of thought, guided by personal experiences, shared stories and an ethics of mutual care, taken up by a diverse participants who range from scholars and industry leaders to graduate students and community members.

Bennett’s appointment comes as current director, Elizabeth Langland, retires from a 16-year career at ASU. Langland previously served as vice provost at the West campus, and has held appointments at the New College for Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the Institute for Humanities Research. She was named director of the Lincoln Center in 2020.

“Gaymon came into the Lincoln Center as associate director when I became director, and he has always been a full partner in all our initiatives,” Langland said. “He is uniquely qualified now to lead the center as its new director, and I am delighted he has agreed to do so.”

Langland and Bennett’s collaborative working relationship began at the IHR’s Future of Humane Technology Symposium in Washington, D.C, in 2019. Under their leadership, the Lincoln Center has refined the design studio toolkit through multiple case studies and has also released projects including the Human Tech Oracle Deck.

With Bennett now at the helm, the center will continue to expand on its implementation of the design studio model while also pursuing new opportunities in teaching, research and the facilitation of ethical inquiry. One of these key initiatives involves research on responsible artificial intelligence innovation, sponsored by the National Humanities Center, which has led to the development of a class on the human impacts of AI that will be taught by Bennett and the center’s research program manager, Erica O’Neil.

“The team at the Lincoln Center has struck a chord in this new moment at the culmination of collective efforts at ASU to interrogate issues around collaborative research and playful experimentation,” Bennett said. “In the humanities, there is a longstanding tradition of the lone genius of scholarly excellence, which has shaped our collective sense of what good work is supposed to look like. There is nothing wrong with specialization and deep learning. But when it comes at the expense of our ability to work inventively with people of other walks of life — including scholarly and scientific walks of life — then our strength becomes an impediment. Learning to reimagine and remake that process, to turn toward new modes of creativity and iterative exploration, requires the very pleasurable work of undoing those habits.

“At the Lincoln Center, we’re asking: What does it mean to make ethics not just part of the scene, but to rethink the pursuit of innovation in ways that improve our collective living?”

More Science and technology

Compact X-ray laser lab aims to reveal deep secrets of life, matter and energy

X-rays allow us to view inside the human body to diagnose broken bones and other hidden problems. More recent X-ray advances are…

Apollo lunar samples enable ASU researcher to pinpoint moon’s crystallization timeline

A team of researchers, including Arizona State University geochemist Melanie Barboni, in collaboration with scientists from The…

NASA launches space telescope to chart the sky and millions of galaxies

California’s Vandenberg Space Force Base was the site for Tuesday’s 8:10 p.m. launch of the NASA SPHEREx mission aboard a SpaceX…