ASU professor's book examines the personal and widespread impact of misinformation

This is the first sentence you’ll see on the website for the three-year project "Recovering Truth: Religion, Journalism and Democracy in a Post-Truth Era":

"We witness today a striking indifference to truth."

The project, developed by Arizona State University’s Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict and the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, brought together journalists and scholars to “create new platforms for thinking and communicating about the pursuit, meaning, discovery and recovery of truth in democratic life.”

“The two groups tend to approach the topic of truth differently,” said Tracy Fessenden, director of strategic initiatives for the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict. “Journalists make it their job to find the truth and tell it. Academics wonder about the nature of truth, the reality of truth, whether truth is discovered or created and, if the latter, whether it can be said to exist at all.”

To be part of the project, ASU Assistant Professor of English Sarah Viren submitted a story from a book she was working on, a book about conspiracy and misinformation and how one person can influence others.

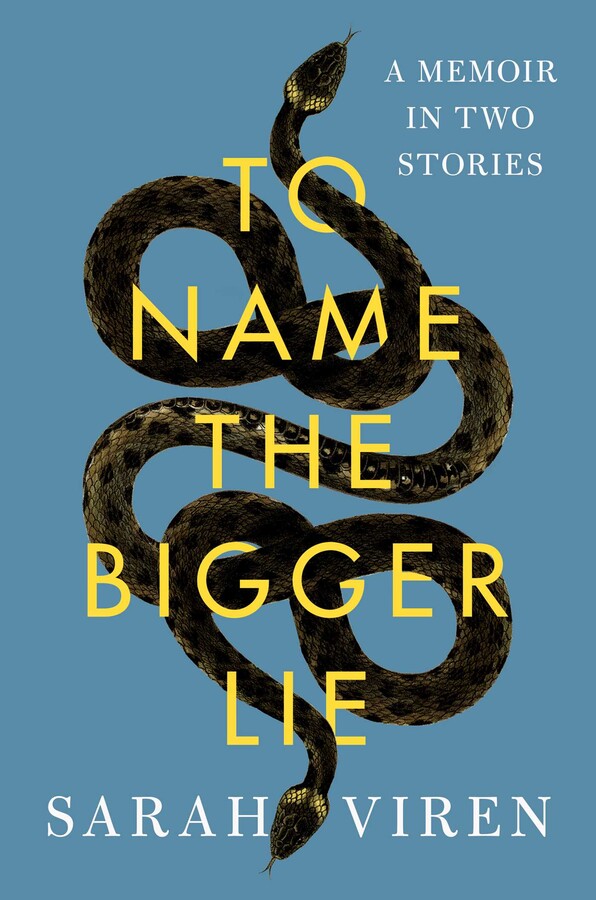

That story — about one of Viren’s high school teachers — opens Viren’s book, “To Name the Bigger Lie: A Memoir in Two Stories,” which was released June 13.

The second story in the book details how Viren’s wife, Marta, was falsely accused of sexual harassment by a man angry that he was passed over for a job Viren was offered.

ASU News talked to Viren about the book, the stories in it and the Recovering Truth project.

Note: The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Question: How would you describe what your book is about?

Answer: It started as a book about my high school teacher, who taught us a version of philosophy that he was taught in the International Baccalaureate program here (in Florida). He got us to sort of think about what is truth, what is the meaning of life, etc. But he had a sort of weird conversion between my ninth grade year and my junior year where he really fell into conspiracy theories and pushing conspiracy theories. I had kind of a break with him in high school when he pushed Holocaust denialism. It was sort of a point where I was like, “This doesn’t make sense anymore.”

So the book started as kind of an investigation of him and his influence over me and my classmates, and grappling with the way he pushed a version of manipulated truth and manipulated reality but under the guise of sort of trying to get people to think about things. That’s the story that opens the book.

Then it's interrupted by a second story, which I wrote about in the New York Times Magazine. (While at ASU) I was offered a job somewhere else. The other candidate who was next in line for the job if I didn’t take it found out about that and tried to manipulate the situation so that basically he could get the job. He pretended to be a woman at ASU who was accusing my wife of sexual harassment. We ended up getting a defamation lawyer in order to figure out that it was him and were able to kind of prove, “Oh, it’s this guy.” Mystery solved, even though it was very traumatic.

So then the book ends up kind of grappling with both of those men and the ways that they manipulated truth and thinking. How do we come to resolution in stories like that? Is it resolution to just have these facts and know that it’s this guy? And what would be a resolution similar for my high school teacher? I ended up interviewing a number of other students who were, I think, more damaged by him, especially one student who was an immigrant from Latvia and had ended up sort of believing in Holocaust nihilism as a Jewish immigrant. So she really felt psychologically messed up by her interactions with him. I was thinking through a lot this idea of reckoning. How do we reckon with the sort of harm that’s done or caused by people like those two men, who are kind of representative of a lot of people that hate truth?

Q: How did your experience with the Recovering Truth project either influence or change the direction of your book?

A: Somebody from the psychology department was there who talked about the way the mind works as far as understanding the truth. There were a number of other journalists and political theorists. Really, what the project did was kind of widen what I was reading and thinking about when trying to grapple with the central questions in this book.

The other thing that really helped is that we read Hannah Arendt on Plato. I really think in some ways Plato’s allegory is inherently flawed because the idea of the allegory is that all of these people are in this cave, and they see these shadows on the wall. They think they’re real, and one person escapes and sees what is real, and that’s outside the cave, and then comes back and rules over those people. But he doesn’t tell them the truth. He just comes back and rules over them. My sort of conclusion or thought was that we really have to find some sort of truth together if we’re all in a cave, right? It has to be about community. It can’t be about this one person that gets out because then you’re always going to have this sort of elitist system.

Q: Did your experience with writing the book and the Recovering Truth project change your mind in any way about how we deal with misinformation?

A: I think before writing the book and being in the project I really did think that things like fact-checking or just identifying lies or manipulation would be a potential way out. Kind of like what happened in our lawsuit. But what I actually found in that experience is that we knew the truth, but that guy continues to lie, right? And there’s some people that believe in him. So, I’m not really sure.

I’m less convinced that just sort of fact-checking or identifying lies is the way forward. I did sort of develop more this idea ... that we need to dialogue with people, especially people we don’t agree with. There was one guy from high school that ended up being really affected by this teacher I had, and I tracked him down and found him on Facebook, and he’s sort of a rabid conspiracy theorist now.

We’ve all seen this on social media. Somebody’s post is fact-checked, and then they get really mad and feel like they’re being censored. So, it doesn’t really work. I do think this model of dialogue and talking … it can seem Pollyannaish, and it feels that way because it’s hard to imagine how it would work, but it does feel like a model we need to try. It’s important to know that people believe something, even if it’s false. ... We have to understand they’re legitimate real people and there’s reasons that they believe what they do.

Top photo from iStock/Getty images

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…