Into the 'Mammalverse': Genomics advances unlock secrets hidden within mammals' genetic blueprints

ASU Assistant Professor Nathan Upham published a perspective article that explores the implications and main advances of six publications by the Zoonomia Consortium on evolutionary history. Photo courtesy Nathan Upham

An Arizona State University researcher recently co-authored a perspective article as part of the special section “Zoonomia” in the renowned journal Science. School of Life Sciences Assistant Professor Nathan Upham and Michael Landis, assistant professor at Washington University, explore the implications and main advances of six publications by the Zoonomia Consortium on evolutionary history and give their view on the future of mammal genomics.

“I think this article expertly highlights some of the most important features of the largest release of mammalian genomes ever,” said Melissa Wilson, an expert in genetics and associate professor in the School of Life Sciences.

The “mammalverse” – as referred to by Upham – encompasses the universe of diverse mammal species, ecologies and genomes to be investigated. Mammal genomics — studying the genes and DNA of mammals — is a fast-growing area of research that can help us learn more about how mammals have evolved and are related to each other, and even discover new ways to improve human and animal health.

Mammals include monkeys, cats, whales, mice, bats and humans. This fascinating group of species has complex genetic codes that determine their characteristics and traits.

Geneticists use advanced techniques and technologies to examine the DNA sequences of different mammals and compare how their genes work. Genomic datasets containing hundreds of mammals’ DNA (or RNA) sequences can provide critical information about evolutionary relationships, genetic diversity and potential health implications.

The Zoonomia Consortium’s new dataset of 240 species’ genomes has unlocked new research at the molecular, individual and population levels among mammals. In their perspective article, Upham and Landis explore such publications and provide additional insights into the field.

“The alignment of whole genomes for these 240 species of placental mammals shows how much we can learn about humans by studying nonhumans,” Upham said.

“We can now better explore all the mammal diversity that is alive today on Earth (6,500 species), including their wide variety of ecological traits (flying to burrowing to fully aquatic) and genomic diversity (transposable elements, enhancers, transcription factors and protein-coding genes). All of this diversity is now beginning to be explored using datasets and tools like those presented in these Zoonomia articles,” he said.

Various cutting-edge techniques and technologies, including high-throughput sequencing, comparative genomics and computational analyses, have allowed scientists to explore the vast complexities of mammalian genomes, including previously unexplored regulating elements.

“The sequencing of genomes from wild mammal species is far more feasible now than it was 20 years ago, thanks to new ultra-long read sequencing technologies that are now able to traverse the highly repetitive DNA regions that are abundant in mammal genomes,” Upham said. As one article in the package found, this “dark matter” of mammal genomes makes up approximately 25–65% of DNA content for typical species.

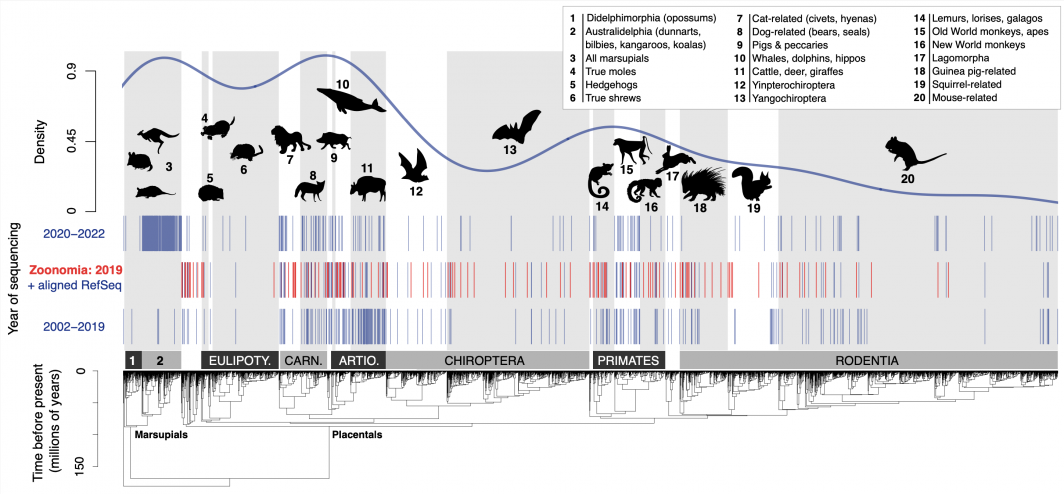

Genomes for 675 mammal species relative to the Mammalia phylogenetic tree of 5,911 living species shows the disproportionate representation of large-bodied species related to cats, dogs, whales, monkeys and some marsupials. Shown is the consensus time-scaled phylogeny from Upham et al. (2019) and genome data downloaded from NCBI on Feb. 9. Photo courtesy Nathan Upham

“As a result, studying the diversity and abundance of different types of transposable elements is now feasible for the first time,” Upham said.

Despite all the significant advances in the field of mammal genomics, there are still several limitations.

“The alignment of these 240 genomes (from the Zoonomia Consorium’s new dataset) is a big advance, but they highlight how little is actually known about the mammalverse of 6,500 living species’ genomes. Only 675 species of mammals have yet had their genomes sequenced, and many of those are low-quality assemblies," Upham said.

In addition, he said there is a large bias in which species have been sequenced, mostly large-bodied and high-latitude species (e.g., species related to cats, dogs, whales, cattle and monkeys). As a result, there is a need to sequence small-bodied bats, rodents and shrews to even out the sampling of genomes.

“Future sequencing of genomes in small-bodied mammals will be valuable, as these species are expected to evolve more rapidly because of large population sizes and short generation times. However, both dynamics can be flipped when small species are range restricted (for example, on mountains or islands) or long lived (such as in some bats like Myotis species), which underscores their value for comparative genomic studies,” Upham and Landis wrote in the article.

Nonetheless, the article shows that the field holds immense potential for enhancing our understanding of mammalian biology, evolution and health, ultimately paving the way for advancements in medicine, conservation and evolutionary biology.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…