When Thomas Czerniawski rides his bicycle to work every day among a sea of cars, he wonders if he might be crazy. In Tempe and the larger Phoenix metropolitan area — a region designed around car infrastructure — it sure can seem that way.

However, he’s far from alone. With the development of Culdesac, a car-free community being built in Tempe, there will soon be many more people living in the area who share a passion for sustainable modes of transportation like biking.

“I want to see our cities facilitating a shift to more sustainable, healthy, cost-effective modes of transportation,” says Czerniawski, an assistant professor of construction engineering in the Del E. Webb School of Construction within the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University.

Czerniawski wanted to use his skills in computer vision, building information modeling and construction management to improve the bicycling experience in his city. By forging new interdisciplinary connections with Assistant Professor Huê-Tâm Jamme and Associate Professor Deborah Salon — ASU urban and environmental planning researchers who are also bicyclists — he is leading a research project to do just that.

In a yearlong project, they’re gathering stories from Tempe bicyclists of all experience levels and pairing their anecdotes with a “digital twin” of the city that can be viewed in virtual reality. Their goal is to share what it’s like to ride a bicycle in the city with stakeholders and potential new bicyclists.

With Tempe infrastructure improvement projects underway and the first cohort of Culdesac residents preparing to move in to more than 700 units planned in the car-free development, their experiment is well-timed to make an impact in the community.

Their work, a project titled “Transforming Tempe into a Bicycling Oasis Through Data-Driven Planning,” is being supported by the Zimin Institute for Smart and Sustainable Cities at ASU. The institute shares a similar vision of people-centered cities that are safer, more sustainable and personally enriching through the use of advanced technology and human connections.

“The project represents an intriguing fusion of technology development and deployment, data science, public safety and public policy,” says Greg Raupp, the Zimin Institute director and a professor of chemical engineering in the Fulton Schools. “The strong, diverse interdisciplinary project team, including active, external community partners Culdesac and the city of Tempe, is led by a project director who is incredibly committed and passionate about the project and working to solve a problem he confronts daily.”

Raupp notes the project is well aligned with a growing worldwide movement to plan, design, build and nurture vibrant micro-communities in larger cities.

“This project can put us at the forefront of realizing such a vision in our own backyard,” he says.

Understanding the transportation landscape through storytelling

Jamme lives in Phoenix and uses her bike and the light rail to get to work. While there are places she bikes that feel unsafe or especially challenging, Jamme finds the area around the ASU Tempe campus to be a pretty good place to bike — “but it’s definitely not yet the bicycle oasis that we’re hoping to build with this project.”

“The main challenge we hear when we talk to people and when we ride our bikes ourselves is that it doesn’t feel safe most of the time,” Jamme says. “It’s frustrating in a way because the weather is such that many months of the year it could be a very pleasant experience.”

Salon recalls positive experiences in other places she’s lived, including Tokyo, Paris and Davis, California — a place she calls the bicycling mecca of the United States. She says Tempe has nice spots for biking, but many routes can be unpleasant.

Living in Tempe since 2014, Salon often walks and rides her bike to work and on errands, but she also has a car out of necessity for her family of four.

“Cars are super useful and an incredible invention, but I think we overuse them. It would be nice if we had a world where we still had cars, but we also made it comfortable and convenient to get around even if you didn’t have a car,” Salon says. “That feels almost like a fantasy land compared to where we are right now in Phoenix.”

Salon’s personal experiences and her research focus on reducing automobile dependence have led her to look critically at the transportation landscape of her city and how it affects her community.

When Jamme joined the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at ASU in 2020 with a similar research focus, she started a collaboration with Salon to study the budding Culdesac development.

“Culdesac is branded as the first car-free neighborhood in the United States, and since it’s happening next door and it’s promoting a very different mobility experience than the dominant one, I was super interested in looking at it very closely,” Jamme says.

Separate from the Zimin Institute-funded project, they’re working on a long-term study to “get a sense of how living at Culdesac changes not only how they move around, but how they organize their lives without access to a private car in a very car-centric city,” Jamme says.

This has given Jamme and Salon a group of potential storytellers in the form of future Culdesac residents and current staff, many of whom are passionate about biking. They’ve also connected with the Tempe Bicycle Action Group and other cyclists through their work.

With the Zimin Institute-funded project, they’re aiming to use their connections to collect stories from bicyclists ranging from new to experienced, hesitant to dedicated, and individuals to families with children. The researchers are also interested in how different types of streets from quiet neighborhood lanes to main arterial roads with or without bike lanes affect the cyclists’ experiences.

Using technology to empower the cycling community

Czerniawski has realized the importance of data in communicating bicycling challenges when attending Tempe public forums.

“There’s usually a lot of enthusiasm, but a lot of what is shared is not very quantitative, and I find that takes away from the credibility,” he says. “This has inspired me to combine (Salon and Jamme’s) community engagement, which collects these kinds of stories, the things that really matter to the people on the ground, and my lab’s quantitative approaches where we’re imaging and collecting bike counts and the like so we can support the stories in a way that gives them more impact.”

Czerniawski is exploring several strategies for data collection and visualization to help share the biking experience more effectively.

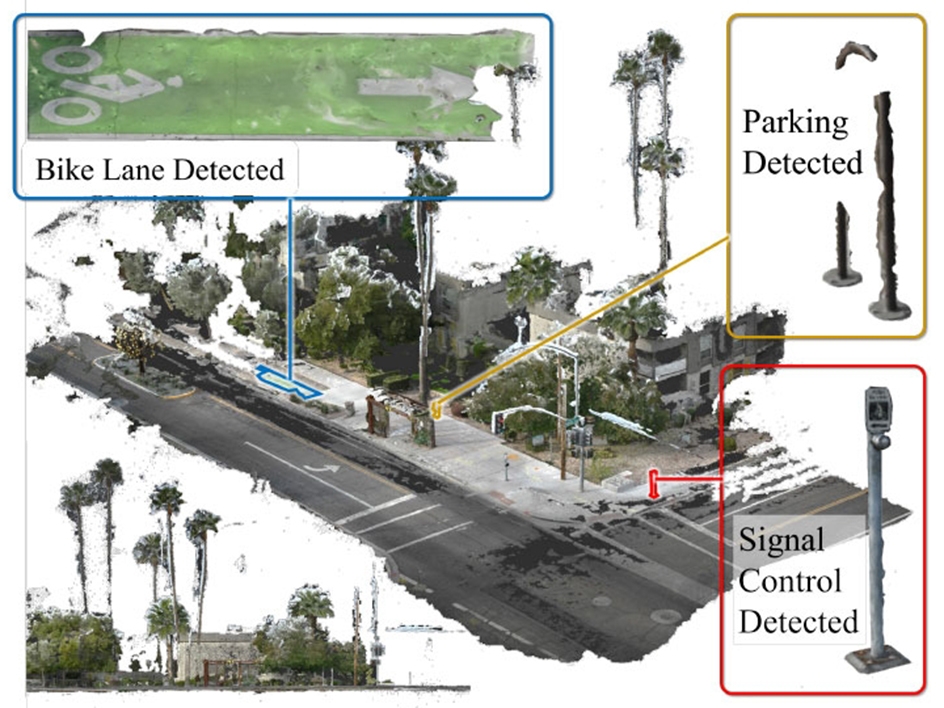

One of the more innovative methods uses lidar laser scanning to capture a 3D image of the city. The system he developed combines SLAM-based mobile mapping with the speed and mobility of electric scooters. Czerniawski and his lab’s student researchers ride an electric scooter while wearing the backpack-sized lidar system and zigzag all around Tempe to capture as much scanned data as they can during the spring.

Lidar systems capable of capturing an entire city can cost up to a million dollars and require a massive system mounted to the back of a truck. The system deployed by Czerniawski’s team is much smaller and a fraction of the cost, which “has opened the gates to academics to perform city-scale scanning” that was only available to municipalities with large budgets, but rarely done.

The lidar data can be used to create a digital model of the city in great detail, something known in Czerniawski’s field as a digital twin. A crude example of a digital twin is the 3D models of buildings displayed on Google Earth.

Alongside the digital twin, the team is capturing video as a final form of data collection that can be viewed on virtual reality headsets to experience a bike route as realistically as possible.

Czerniawski is also developing a computer-vision-based bike counting technique to more accurately quantify the number of people affected by certain issues in the bicycling infrastructure, which would also contribute to the quantitative data needed to meaningfully impact policy.

Combining these techniques with Jamme and Salon’s work has led to something different than what any of the researchers experience in their typical work.

“When I’ve worked with travel behavior researchers who are engineers, I’ve always felt like the research wasn’t truly interdisciplinary in a way where there was real value added. Whereas with Thomas, this is interdisciplinary research,” Salon says. “This guy has amazing skills that are really different from other skills that we have, and we each bring something to the project. I think it makes the project a lot better.”

Creating an impactful experience

While the team is just getting started with the data collection and interview process, they envision the outcome of their work to be an interactive presentation to city stakeholders and community members in the ASU Decision Theater in the fall.

Czerniawski sees the possibility to show the barriers and enablers to people deciding to use a bicycle for transportation, the impact of infrastructure development on the biking experience, and many other opportunities based on the stories people tell them.

“We’re going to collect video of a few key areas of the city that pop up during our interviews with the community,” Czerniawski says. “We will combine the data and the stories to paint a picture of the routes and their issues as well as offer people the opportunity to just experience a route and explore.”

The team hopes that by providing as close to a firsthand experience of biking in Tempe as possible, they can help even one person to use their bike more often, or even help decision-makers be more sympathetic to bicyclists’ experiences to make better policies down the road.

“I feel like we’re creating a museum exhibit,” Salon says. “The idea of museum exhibits is often to give people experiences that they can’t have, that they wouldn’t just have naturally. Those experiences may be fun or may be scary, but certainly educational and hopefully lead you to have a greater understanding of the world and of other people’s experience in it.”

Top photo: The ASU research team reviews a bicycling map for Tempe. The team has noticed a common problem with bicycling in Tempe from their own experiences and from others they’ve talked to — it often feels unsafe or challenging to bike here. They hope to help bring attention to the issues and highlight the positive aspects of biking with their research project. Photo by Erika Gronek/ASU

More Science and technology

ASU technical innovation enables more reliable and less expensive electricity

Growing demand for electricity is pushing the energy sector to innovate faster and deploy more resources to keep the lights on and costs low. Clean energy is being pursued with greater fervor,…

What do a spacecraft, a skeleton and an asteroid have in common? This ASU professor

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft will probe an asteroid as it flys by it on Sunday — one with a connection to the mission name.The asteroid is named Donaldjohanson, after Donald Johanson, who founded Arizona…

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…