While most of us were celebrating the holidays, a spacecraft called the Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO) was tucking itself into orbit around the moon. A few weeks later, its first images were ready to share.

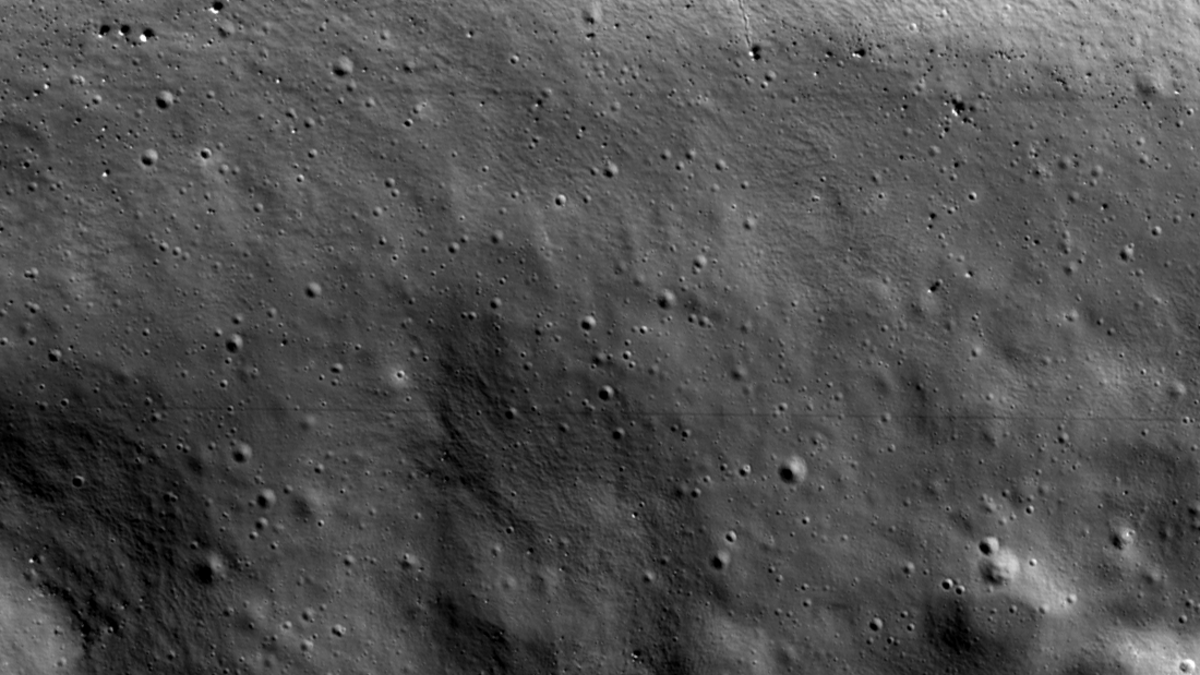

Bolted on to one side of KPLO is ShadowCam, a NASA instrument. It’s a camera that can see into the dark, unlit areas of the moon’s permanently shadowed craters — places astronomers have never seen. ShadowCam’s first image is of an area inside the Shackleton Crater, near the lunar south pole. ShadowCam is now sending back more images and checking its systems.

“The most important thing is to know the truth,” said ShadowCam Deputy Principal Investigator Prasun Mahanti. “In order to do that, we must make sure the camera is really telling us what we need it to tell. So this is the calibration month. This is the month where we check that. This is when our report cards come out for the camera.

“And then from February is when the mission campaigning, the mapping, really, really starts,” added Mahanti, an assistant research scientist for Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Video by Steve Filmer/ASU

Space scientists say those permanently shadowed craters are some of the coldest places in our solar system. That’s one reason they may contain water ice.

“So you might ask, 'Where does this water come from?'” said NASA Principal Investigator Mark Robinson, adding that this question comes up a lot when he describes the mission.

“Well, we know that comets impact the moon; small ones, medium ones, every day. These objects hit the Earth, but the Earth’s atmosphere protects us. And so they burn up in the upper atmosphere and we don't ever see them. But when they hit on the moon, most of that, those volatiles end up going back out into space. But a small percentage of them, through random hops, land in these permanently shadowed craters, and they can collect there.

“So the big question is ... how much water is there? How much of these other volatiles are there? We don't know.”

But ShadowCam’s science isn’t just a wild gamble.

“Right now, we have hints that they're there from much lower-resolution experiments like radar, neutrons maps and ultraviolet imaging,” said Robinson, a professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

“But it's all, you know, fuzzy, so to speak. The picture's really fuzzy. So we're trying to sharpen the picture down to the scale of a meter of what it looks like inside these craters.”

He said it will take about six months to one year to generate enough images from these dark places to draw some conclusions. Robinson and his team have been operating NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera since 2009 from inside ASU’s science operations center.

See the first image and future images at ASU’s ShadowCam website. KPLO is operated by the Korea Aerospace Research Institute, and updates can be found on its mission website.

Top photo: The first ShadowCam image from orbit reveals the permanently shadowed wall and floor of Shackleton Crater in never-before-seen detail. Image by NASA/KARI/Arizona State University

More Science and technology

ASU-led Southwest Advanced Prototyping Hub awarded $21.3M for 2nd year of funding for microelectronics projects

The Southwest Advanced Prototyping (SWAP) Hub, led by Arizona State University, has been awarded $21.3 million in Year 2 funding under the CHIPS and Science Act to continue its work advancing the…

Celebrating '20 Years of Discovery' at the Biodesign Institute

Editor’s note: The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University wraps up its 20th anniversary with the sixth and final installment of its "20 Years of Discovery" series. Each story highlights…

Student research supports semiconductor sustainability

As microelectronics have become an increasingly essential part of modern society, greenhouse gas emissions, which are associated with their use and manufacture, have increased in tandem.…