Webb telescope PEARLS project unveils exquisite views of distant galaxies

A swath of sky measuring 2% of the area covered by the full moon was imaged with Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) in eight filters, and with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and Wide-Field Camera 3 (WFC3) in three filters that together span the 0.25 to 5 micron wavelength range. This image represents a portion of the full PEARLS field, which will be about four times larger. Image courtesy NASA, ESA, CSA, Rolf A. Jansen (ASU), Jake Summers (ASU), Rosalia O'Brien (ASU), Rogier Windhorst (ASU), Aaron Robotham (UWA), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI), Christopher Willmer (University of Arizona) and the JWST PEARLS Team; Image processing by Rolf A. Jansen (ASU) and Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

For decades, the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based telescopes have provided us with spectacular images of galaxies. This all changed when the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launched in December 2021 and successfully completed commissioning during the first half of 2022. For astronomers, the universe, as we had seen it, is now revealed in a new way never imagined by the telescopes's Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) instrument.

The NIRCam is Webb's primary imager that covers the infrared wavelength range from 0.6 to 5 microns. NIRCam detects light from the earliest stars and galaxies in the process of formation, the population of stars in nearby galaxies, as well as young stars in the Milky Way and Kuiper Belt objects.

The Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing Science, or PEARLS, project is the subject of a recent study published in Astronomical Journal by a team of researchers, including Arizona State University School of Earth and Space Exploration Regents Professor Rogier Windhorst, Research Scientist Rolf Jansen, Associate Research Scientist Seth Cohen, Research Assistant Jake Summers and Graduate Associate Rosalia O'Brien, along with the contribution of many other researchers.

For researchers, the PEARLS program's images of the earliest galaxies show the amount of gravitational lensing of objects in the background of massive clusters of galaxies, allowing the team to see some of these very distant objects. In one of these relatively deep fields (shown in the image above), the team has worked with stunning multicolor images to identify interacting galaxies with active nuclei.

Windhorst and his team's data show evidence for giant black holes in their center where you can see the accretion disc — the stuff falling into the black hole, shining very brightly in the galaxy center. Plus, lots of galactic stars show up like drops on your car's windshields — like you're driving through intergalactic space. This colorful field is straight up from the ecliptic plane, the plane in which the Earth and the moon, and all the other planets, orbit around the sun.

"For over two decades, I've worked with a large international team of scientists to prepare our Webb science program," Windhorst said. "Webb's images are truly phenomenal, really beyond my wildest dreams. They allow us to measure the number density of galaxies shining to very faint infrared limits and the total amount of light they produce. This light is much dimmer than the very dark infrared sky measured between those galaxies."

MORE: View a zoomable version of the image above and learn more about PEARLS project

The first thing the team can see in these new images is that many galaxies that were next to or truly invisible to Hubble are bright in the images taken by Webb. These galaxies are so far away that the light emitted by stars has been stretched.

The team focused on the North Ecliptic Pole time domain field with the Webb telescope — easily viewed due to its location in the sky. Windhorst and the team plan to observe it four times.

The first observations, consisting of two overlapping tiles, produced an image that shows objects as faint as the brightness of 10 fireflies at the distance of the moon (with the moon not there). The ultimate limit for Webb is one or two fireflies. The faintest reddest objects visible in the image are distant galaxies that go back to the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Photo courtesy NASA, ESA, CSA, Rolf A. Jansen (ASU), Jake Summers (ASU), Rosalia O'Brien (ASU), Rogier Windhorst (ASU), Aaron Robotham (UWA), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI), Christopher Willmer (University of Arizona) and the JWST PEARLS Team; Image processing by Rolf A. Jansen (ASU) and Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

For most of Jansen's career, he's worked with cameras on the ground and in space, where you have a single instrument with a single camera that produces one image. Now scientists have an instrument that has not just one detector or one image coming out of it, but 10 simultaneously. For every exposure NIRCam takes, it gives 10 of these images. That's a massive amount of data, and the sheer volume can be overwhelming.

To process that data and channel it through the analysis software of collaborators around the globe, Summers has been instrumental.

“The JWST images far exceed what we expected from my simulations prior to the first science observations,” Summers said. “Analyzing these JWST images, I was most surprised by their exquisite resolution.”

Jansen’s primary interest is to figure out how galaxies like our own Milky Way came to be. And the way to do that is by looking far back in time at how galaxies came together, seeing how they evolved, effectively, and so tracing the path from the Big Bang to people like us.

"I was blown away by the first PEARLS images," Jansen said. "Little did I know, when I selected this field near the North Ecliptic Pole, that it would yield such a treasure trove of distant galaxies, and that we would get direct clues about the processes by which galaxies assemble and grow — I can see streams, tails, shells and halos of stars in their outskirts, the leftovers of their building blocks."

Third-year astrophysics graduate student O'Brien designed algorithms to measure faint light between the galaxies and stars that first catch our eye.

"The diffuse light that I measured in between stars and galaxies has cosmological significance, encoding the history of the universe," O'Brien said. "I feel fortunate to start my career right now — JWST data is like nothing we have ever seen, and I'm excited about the opportunities and challenges it offers."

“I expect that this field will be monitored throughout the JWST mission, to reveal objects that move, vary in brightness or briefly flare up, like distant exploding supernovae or accreting gas around black holes in active galaxies,” Jansen said.

Video by Steve Filmer/ASU Media Relations

More Science and technology

When facts aren’t enough

In the age of viral headlines and endless scrolling, misinformation travels faster than the truth. Even careful readers can be…

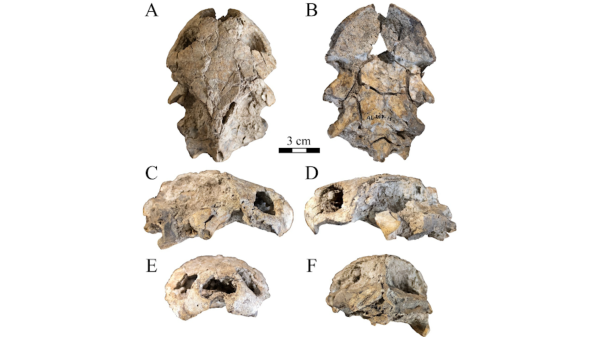

Scientists discover new turtle that lived alongside 'Lucy' species

Shell pieces and a rare skull of a 3-million-year-old freshwater turtle are providing scientists at Arizona State University with…

ASU named one of the world’s top universities for interdisciplinary science

Arizona State University has an ambitious goal: to become the world’s leading global center for interdisciplinary research,…