Drylands are not only home to more than 2 billion people across the globe but are vital to global food and nutrition security.

Defined as lands having a scarcity of water, they encompass 40% of the global terrestrial surface and include the world’s deserts, savannas and shrublands. They house a variety of unique plant and animal biodiversity, and play an important role in climate regulation, with nearly 35% of carbon sequestration in dryland soils.

In short, the health of our drylands is vital to global sustainability.

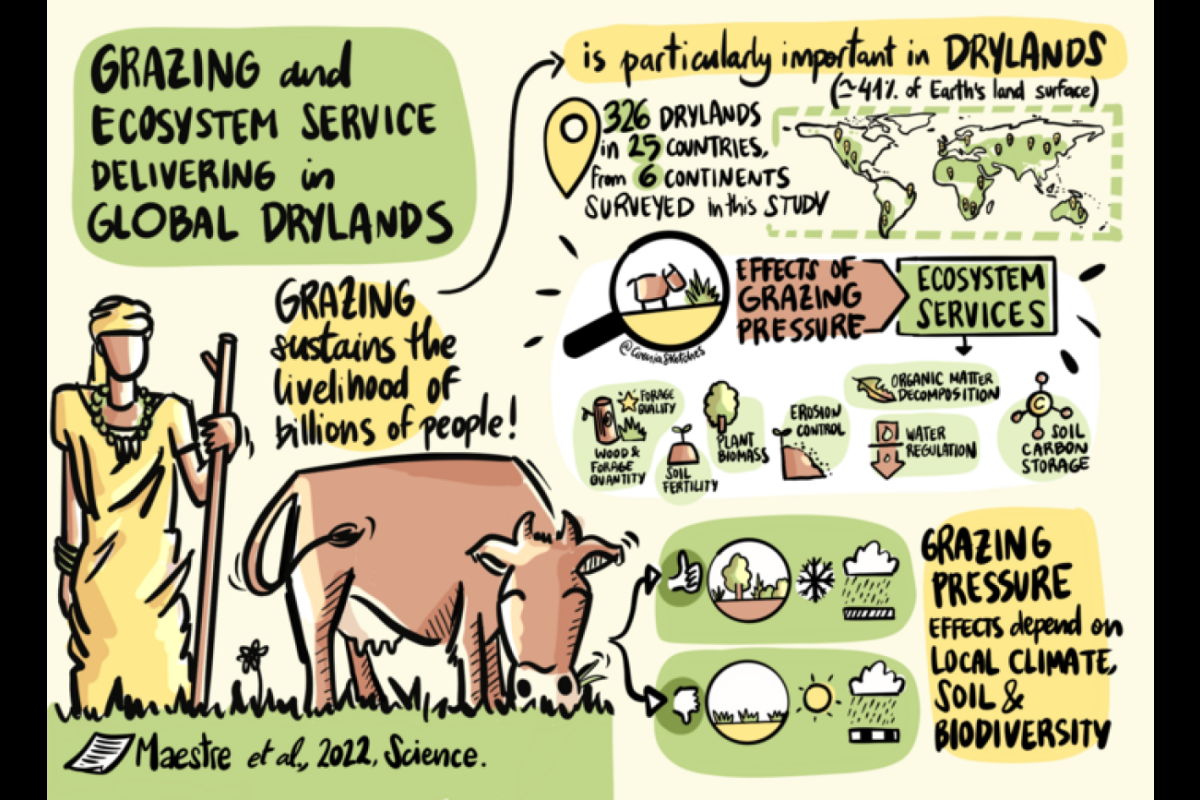

A new study published in the journal Science and led by Fernando T. Maestre of the University of Alicante, Spain, provides the first global field assessment of the ecological impacts of livestock grazing across drylands, surveying 98 dryland sites spanning six continents and representing a key advance toward understanding the global sustainability of these critical ecosystems.

ASU News spoke with Osvaldo Sala, Arizona State University Regents Professor, founding director of ASU’s Global Drylands Center and co-author of the study, about the work.

Osvaldo Sala

Question: First, can you tell us why drylands are important for us to study?

Answer: The sustainability of drylands is not only a topic that is just important, but studying it is our responsibility. Phoenix is located in a dryland. As people who live in drylands, as it says in our ASU charter, it's our commitment to our community. We are embedded in the drylands. We are a university that is in the drylands. It is not a choice, it's our mandate. This is why we focus on the sustainability of drylands.

Q: What makes this study unique from others studying drylands in the past?

A: If you want to understand the sustainability of drylands, you need to understand all drylands. The strength of this study is how global it is. This paper brought together hundreds of authors. We identified 98 sites around the globe and measured variables across the globe.

You cannot find all the important variables like grazing effect or climatic patterns in any specific location. Rather, you need to have experiments that are replicated all over the world. We looked at the effect of grazing, biodiversity and precipitation among the 98 sites. Drylands vary; there are drylands across the globe that are wetter and drier, sites that vary in temperature, and there are cooler grasslands and dryer grasslands. We then looked at how they affect different groups of ecosystem services.

Q: What are ecosystem services?

A: Ecosystem services are the goods and services that nature provides to humans. It's a very anthropocentric, or human-centered, view of what the ecosystem can contribute to the well-being of humans. There are four kinds of ecosystem services. The easiest to understand is the provisioning ecosystem services, and these are things like produce, meat and milk, and fiber. But also there are other ecosystem services that they call supporting ecosystem services, that support other ecosystem services. (And there are) regulating ecosystem services that regulate the water cycle, the climate cycle and sequester carbon. And last, the fourth group, is the cultural ecosystem services. The cultural ecosystem services depend on where you are, but it may include recreation; people use the drylands to hike, but also native Indigenous populations find cultural or religious value in different places.

Q: What were some key conclusions from the research?

A: One of the overall conclusions is that grazing has a positive effect on drylands that are in cooler climates. Grazing affects mostly those warm grasslands and minimally affects the cold grasslands. So there's a temperature grazing interaction.

Grazing is what is most important because grazing is what humans manage. They cannot manage temperature, they cannot manage precipitation. But it is important to understand those patterns, especially in a world that is moving into a different climate.

Q: Now that we have these global results on how grazing affects dryland ecosystems around the world, what's next? What does this mean for the future understanding of drylands?

A: There has never been a global view of drylands before this publication. We previously had individual pieces here. There is a lot of research and a lot of studies attracted by drylands, but this represents a level of comprehensive understanding that we didn't have before.

Top photo: Patagonian steppe (Argentina), courtesy Juan José Gaitán

More Environment and sustainability

2 ASU faculty elected as AAAS Fellows

Two outstanding Arizona State University faculty spanning the physical sciences, psychological sciences and science policy have been named Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of…

Homes for songbirds: Protecting Lucy’s warblers in the urban desert

Each spring, tiny Lucy’s warblers, with their soft gray plumage and rusty crown, return to the Arizona desert, flitting through the mesquite branches in search of safe places to nest.But as urban…

Public education project brings new water recycling process to life

A new virtual reality project developed by an interdisciplinary team at Arizona State University has earned the 2025 WateReuse Award for Excellence in Outreach and Education. The national …